This is the second of four posts on the Corded Ware—Uralic identification:

- Corded Ware—Uralic (I): Differences and similarities with Yamna

- Corded Ware—Uralic (II): Finno-Permic and the expansion of N-L392/Siberian ancestry

- Corded Ware—Uralic (III): “Siberian ancestry” and Ugric-Samoyedic expansions

- Corded Ware—Uralic (IV): Haplogroups R1a and N in Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic

I read from time to time that “we have not sampled Uralic speakers yet”, and “we are waiting to see when Uralic-speaking peoples are sampled”. Are we, though?

Proto-language homelands are based on linguistic data, such as guesstimates for dialectal evolution, loanwords and phonetic changes for language contacts, toponymy for ancient territories, etc. depending on the available information. The trace is then followed back, using available archaeological data, from the known historic speakers and territory to the appropriate potential prehistoric cultures. Only then can genetic analyses help us clarify the precise prehistoric population movements that better fit the models.

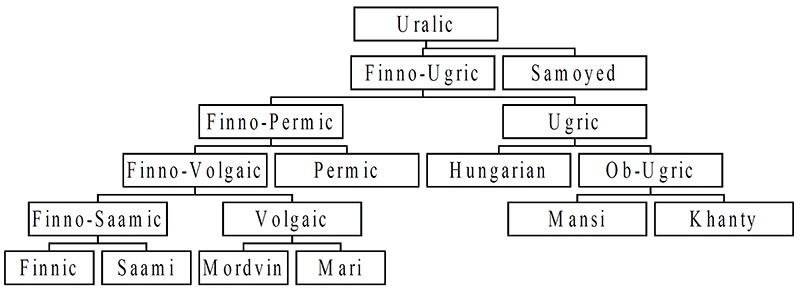

The linguistic homeland

We thought – using linguistic guesstimates and fitting prehistoric cultures and their expansion – that Yamna was the Late Proto-Indo-European culture, so when Yamna was sampled, we had Late Proto-Indo-Europeans sampled. Simple deduction.

We thought that north-eastern Europe was a Uralic-speaking area during the Neolithic:

- For those supporting a western continuity (and assuming CWC was Indo-European), the language was present at least since the Comb Ware culture, potentially since the Mesolithic.

- For those supporting a late introduction into Finland, Uralic expanded the latest with Abashevo-related movements after its incorporation of Volosovo and related hunter-gatherers.

The expansion to the east must have happened through progressive infiltrations with Seima-Turbino / Andronovo-related expansions.

Finding the linguistic homeland going backwards can be described today as follows:

I. Proto-Fennic homeland

Based on the number of Baltic loanwords, not attested in the more eastern Uralic branches (and reaching only partially Mordvinic), the following can be said about western Finno-Permic languages (Junttila 2014):

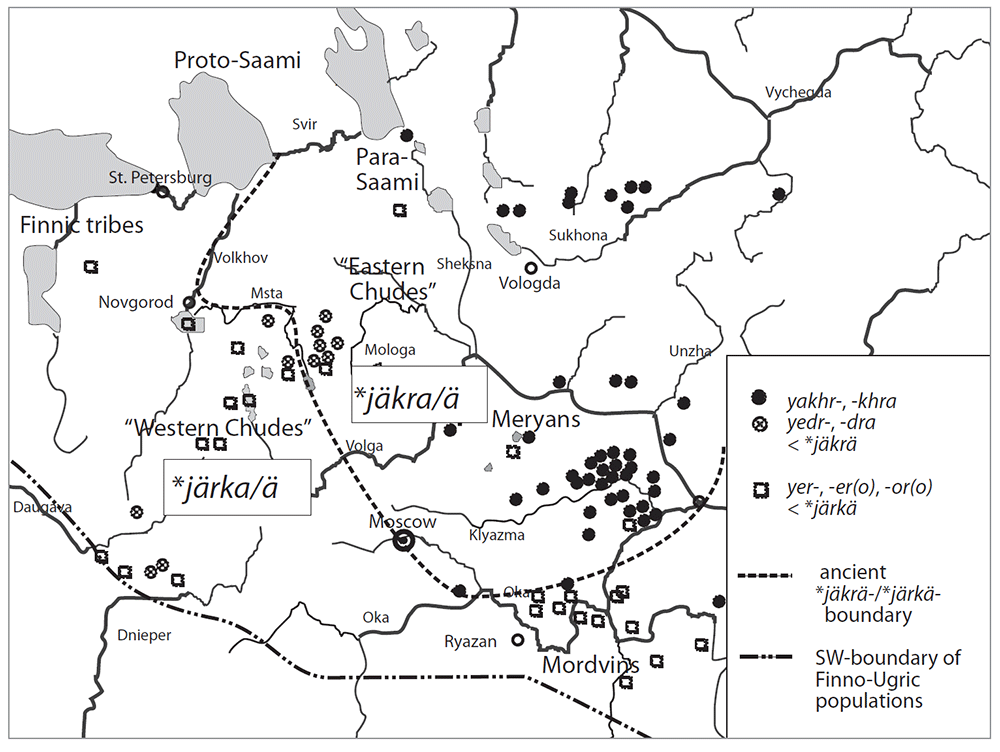

The Volga-Kama Basin lies still too far east to be included in a list of possible contact locations. Instead, we could look for the contact area somewhere between Estonia in the west and the surroundings of Moscow in the east, a zone with evidence of Uralic settlement in the north and Baltic on the south side.

The only linguistically well-grounded version of the Stone Age continuation theory was presented by Mikko Korhonen in 1976. Its validity, however, became heavily threatened when Koivulehto 1983a-b proved the existence of a Late Proto-Indo-European or Pre-Baltic loanword layer in Saami, Finnic, and Mordvinic. Since this layer must precede the Baltic one and it was presumably acquired in the Baltic Sea region, Koivulehto posited it on the horizon of the Battle Axe period. This forces a later dating for the Baltic–Finnic contacts.

Today the Battle Axe culture is dated at 3200 to 3000 BC, a period far too remote to correspond linguistically with Proto-Baltic (Kallio 1998a).

Since the Baltic contacts began at a very initial phase of Proto-Finnic, the language must have been relatively uniform at that time. Hence, if we consider that the layer of Baltic loanwords may have spread over the Gulf of Finland at that time, we could also insist that the whole of the Proto-Finnic language did so.

II. Proto-Finno-Saamic homeland

The evidence of continued Palaeo-Germanic loanwords (from Pre- to Proto-Germanic stages) is certainly the most important data to locate the Finno-Saamic homeland, and from there backwards into the true Uralic homeland. Following Kallio (2017):

(…) the loanword evidence furthermore suggests that the ancestors of Finnic and Saamic had at least phonologically remained very close to Proto-Uralic as late as the Bronze Age (ca. 1700–500 BC). In particular, certain loanwords, whose Baltic and Germanic sources point to the first millennium BC, after all go back to the Finno-Saamic proto-stage, which is phonologically almost identical to the Uralic proto-stage (see especially the table in Sammallahti 1998: 198–202). This being the case, Dahl’s wave model could perhaps have some use in Uralic linguistics, too.

The presence of Pre-Germanic loanwords points rather to the centuries around the turn of the 2nd – 1st millennium BC or earlier. Proto-Germanic words must have been borrowed before the end of Germanic influence in the eastern Baltic at the beginning of the Iron Age, which sets a clear terminus ante quem ca. 800 BC.

The arrival of Bell Beaker peoples in Scandinavia ca. 2350 BC, heralding the formation of the Dagger Period, as well as the development of Pre-Germanic in common with Finnic-like populations point to the late 3rd / early 2nd millennium BC as the first time of close interaction through the Baltic region.

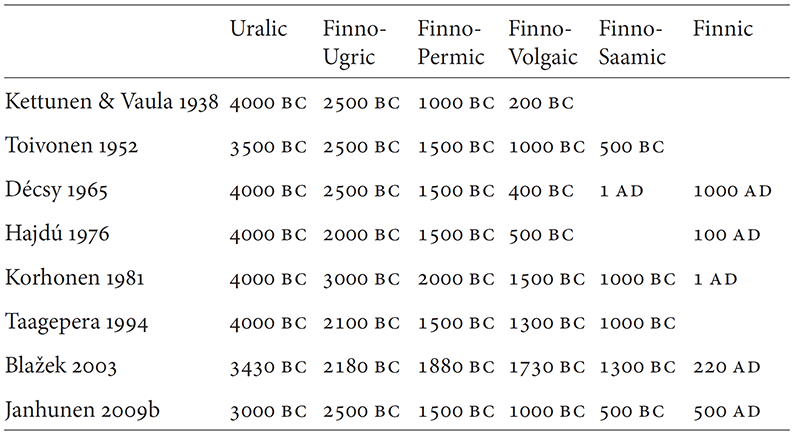

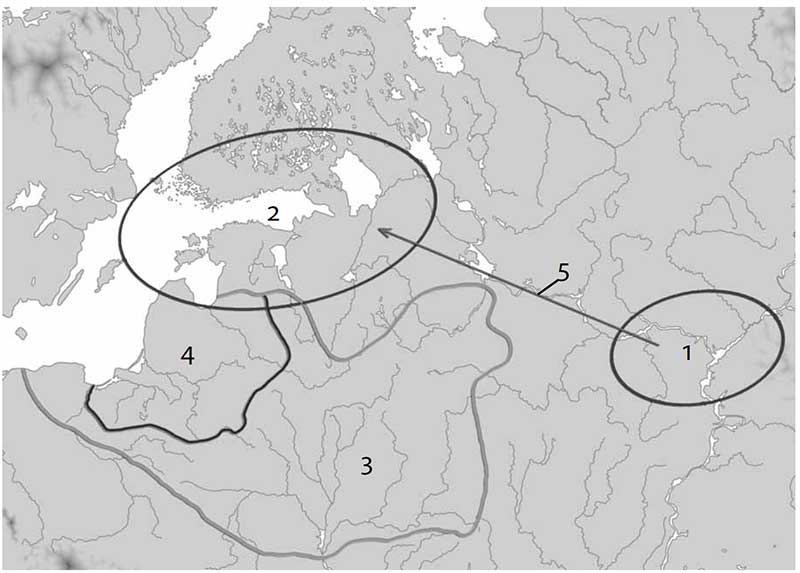

III. Proto-Uralic homeland

(…) the earliest Indo-European loanwords in the Uralic languages (…) show that Proto-Uralic cannot have been spoken much earlier than Proto-Indo-European dated about 3500 BC (Koivulehto 2001: 235, 257). As the same loanword evidence naturally also shows that the Uralic and Indo-European homelands were not located far from one another, the Uralic homeland can most likely be located in the Middle and Upper Volga region, right north of the Indo-European homeland*. From the beginning of the Subneolithic period about 5900 BC onwards, this region was an important innovation centre, from where several cultural waves spread to the Finnish Gulf area, such as the Sperrings Ware wave about 4900 BC, the Combed Ware wave about 3900 BC, and the Netted Ware wave about 1900 BC (Carpelan & Parpola 2001: 78–90).

The mainstream position is nowadays trying to hold together the traditional views of Corded Ware as Indo-European, and a Uralic Fennoscandia during the Bronze Age.

The following is an example of how this “Volosovo/Forest Zone hunter-gatherer theory” of Uralic origins looks like, as a ‘mixture’ of cultures and languages that benefits from the lack of genetic data for certain regions and periods (taken from Parpola 2018):

The Corded Ware (or Battle Axe) culture intruded into the Eastern Baltic and coastal Finland already around 3100 BCE. The continuity hypothesis maintains that the early Proto-Finnic speakers of the coastal regions, who had come to Finland in the 4th millennium BCE with the Comb-Pitted Ware, coexisted with the Corded Ware newcomers, gradually adopting their pastoral culture and with it a number of NW-IE loanwords, but assimilating the immigrants linguistically.

The fusion of the Corded Ware and the local Comb-Pitted Ware culture resulted into the formation of the Kiukais culture (c. 2300–1500) of southwestern Finland, which around 2300 received some cultural impulses from Estonia, manifested in the appearance of the Western Textile Ceramic (which is different from the more easterly Textile Ceramic or Netted Ware, and which is first attested in Estonia c. 2700 BCE, cf. Kriiska & Tvauri 2007: 88), and supposed to have been accompanied by an influx of loanwords coming from Proto-Baltic. At the same time, the Kiukais culture is supposed to have spread the custom of burying chiefs in stone cairns to Estonia.

The coming of the Corded Ware people and their assimilation created a cultural and supposedly also a linguistic split in Finland, which the continuity hypothesis has interpreted to mean dividing Proto-Saami-Finnic unity into its two branches. Baltic Finnic, or simply Finnic, would have emerged in the coastal regions of Finland and in the northern East Baltic, while preforms of Saami would have been spoken in the inland parts of Finland.

The Nordic Bronze Age culture, correlated above with early Proto-Germanic, exerted a strong influence upon coastal Finland and Estonia 1600–700 BCE. Due to this, the Kiukais culture was transformed into the culture of Paimio ceramics (c. 1600–700 BCE), later continued by Morby ceramics (c. 700 BCE – 200 CE). The assumption is that clear cultural continuity was accompanied by linguistic continuity. Having assimilated the language of the Germanic traders and relatively few settlers of the Bronze Age, the language of coastal Finland is assumed to have reached the stage of Proto-Finnish at the beginning of the Christian era. In Estonia, the Paimio ceramics have a close counterpart in the contemporaneous Asva ceramics.

Eastern homelands?

I will not comment on Siberian or Central Asian homeland proposals, because they are obviously not mainstream, still less today when we know that Uralic was certainly in contact with Proto-Indo-European, and then with Pre- and Proto-Indo-Iranian, as supported even by the Copenhagen group in Damgaard et al. (2018).

This is what Kallio (2017) has to say about the agendas behind such proposals:

Interestingly, the only Uralicists who generally reject the Central Russian homeland are the Russian ones who prefer the Siberian homeland instead. Some Russians even advocate that the Central Russian homeland is only due to Finnish nationalism or, as one of them put it a bit more tactfully, “the political and ideological situation in Finland in the first decades of the 20th century” (Napolskikh 1995: 4).

Still, some Finns (and especially those who also belong to the “school who wants it large and wants it early”) simultaneously advocate that exactly the same Central Russian homeland is due to Finnlandisierung (Wiik 2001: 466).

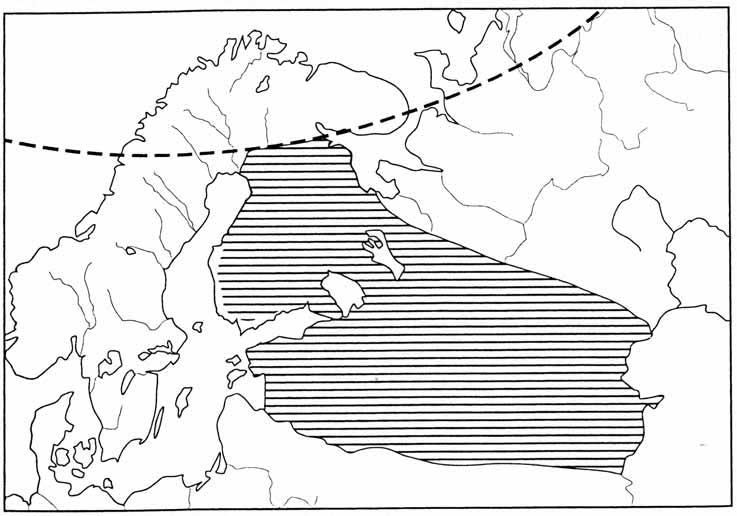

Hence, for those of you willing to learn about fringe theories not related to North-Eastern Europe, you also have then the large and early version of the Uralic homeland, with Wiik’s Palaeolithic continuity of Uralic peoples spread over all of eastern and central Europe (hence EHG and R1a included):

These fringe Finnish theories look a lot like the Corded Ware expansion… Better not go the Russian or Finnish nationalist ways? Agreed then, let’s discuss only rational proposals based on current data.

The archaeological homeland

For a detailed account of the Corded Ware expansion with Battle Axe, Fatyanovo-Balanovo, and Abashevo groups into the area, you can read my recent post on the origin of R1a-Z645.

1. Textile ceramics

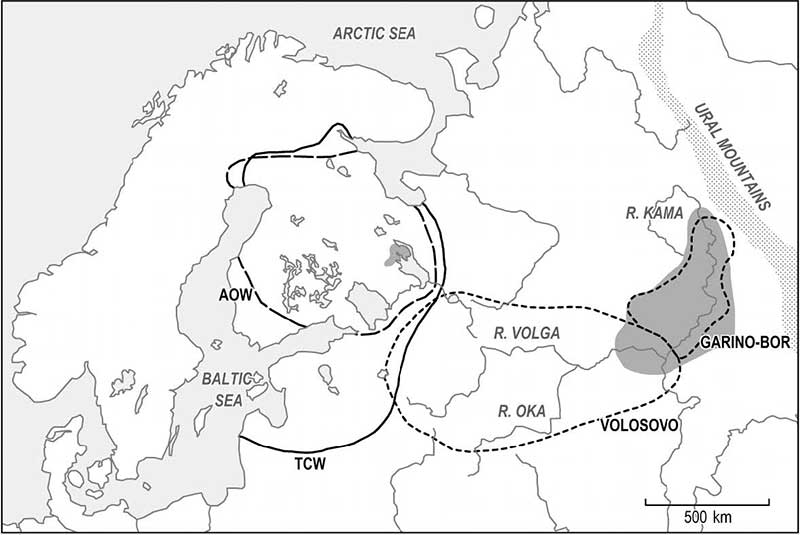

During the 2nd millennium BC, textile impressions appear in pottery as a feature across a wide region, from the Baltic area through the Volga to the Urals, in communities that evolve from late Corded Ware groups without much external influence.

While it has been held that this style represents a north-west expansion from the Volga region (with the “Netted Ware” expansion), there are actually at least two original textile styles, one (earlier) in the Gulf of Finland, common in the Kiukainen pottery, which evolves into the Textile ware culture proper, and another which seems to have an origin in the Middle Volga region to the south-east.

The Netted ware culture is the one that apparently expands into inner Finland – a region not densely occupied by Corded Ware groups until then. There are, however, no clear boundaries between groups of both styles; textile impressions can be easily copied without much interaction or population movement; and the oldest textile ornamentation appeared on the Gulf of Finland. Hence the tradition of naming all as groups of Textile ceramics.

The fact that different adjacent groups from the Gulf of Finland and Forest Zone share similar patterns making it very difficult to differentiate between ‘Netted Ware’ or ‘Textile Ware’ groups points to:

- close cultural connections that are maintained through the Gulf of Finland and the Forest Zone after the evolution of late Corded Ware groups; and

- no gross population movements in the original Battle Axe / Fatyanovo regions, except for the expansion of Netted Ware to inner Finland, Karelia, and the east, where the scattered Battle Axe finds and worsening climatic conditions suggest most CWC settlements disappeared at the end of the 3rd millennium BC and recovered only later.

NOTE. This lack of population movement – or at least significant replacement by external, non-CWC groups – is confirmed in genetic investigation by continuity of CWC-related lineages (see below).

The technology present in Textile ceramics is in clear contrast to local traditions of sub-Neolithic Lovozero and Pasvik cultures of asbestos-tempered pottery to the north and east, which point to a different tradition of knowledge and learning network – showing partial continuity with previous asbestos ware, since these territories host the main sources of asbestos. We have to assume that these cultures of northern and eastern Fennoscandia represent Palaeo-European (eventually also Palaeo-Siberian) groups clearly differentiated from the south.

The Chirkovo culture (ca. 1800-700 BC) forms on the middle Volga – at roughly the same time as Netted Ware formed to the west – from the fusion of Abashevo and Balanovo elites on Volosovo territory, and is also related (like Abashevo) to materials of the Seima-Turbino phenomenon.

Bronze Age ethnolinguistic groups

In the Gulf of Finland, Kiukainen evolves into the Paimio ceramics (in Finland) — Asva Ware (in Estonia) culture, which lasts from ca. 1600 to ca. 700 BC, probably representing an evolving Finno-Saamic community, while the Netted Ware from inner Finland (the Sarsa and Tomitsa groups) and the groups from the Forest Zone possibly represent a Volga-Finnic community.

NOTE. Nevertheless, the boundaries between Textile ceramic groups are far from clear, and inner Finland Netted Ware groups seem to follow a history different from Netted Ware groups from the Middle and Upper Volga, hence they could possibly be identified as an evolving Pre-Saamic community.

Based on language contacts, with Early Baltic – Early Finnic contacts starting during the Iron Age (ca. 500 BC onwards), this is a potential picture of the situation at the end of this period, when Germanic influence on the coast starts to fade, and Lusatian culture influence is stronger:

The whole Finno-Permic community remains thus in close contact, allowing for the complicated picture that Kallio mentions as potentially showing Dahl’s wave model for Uralic languages.

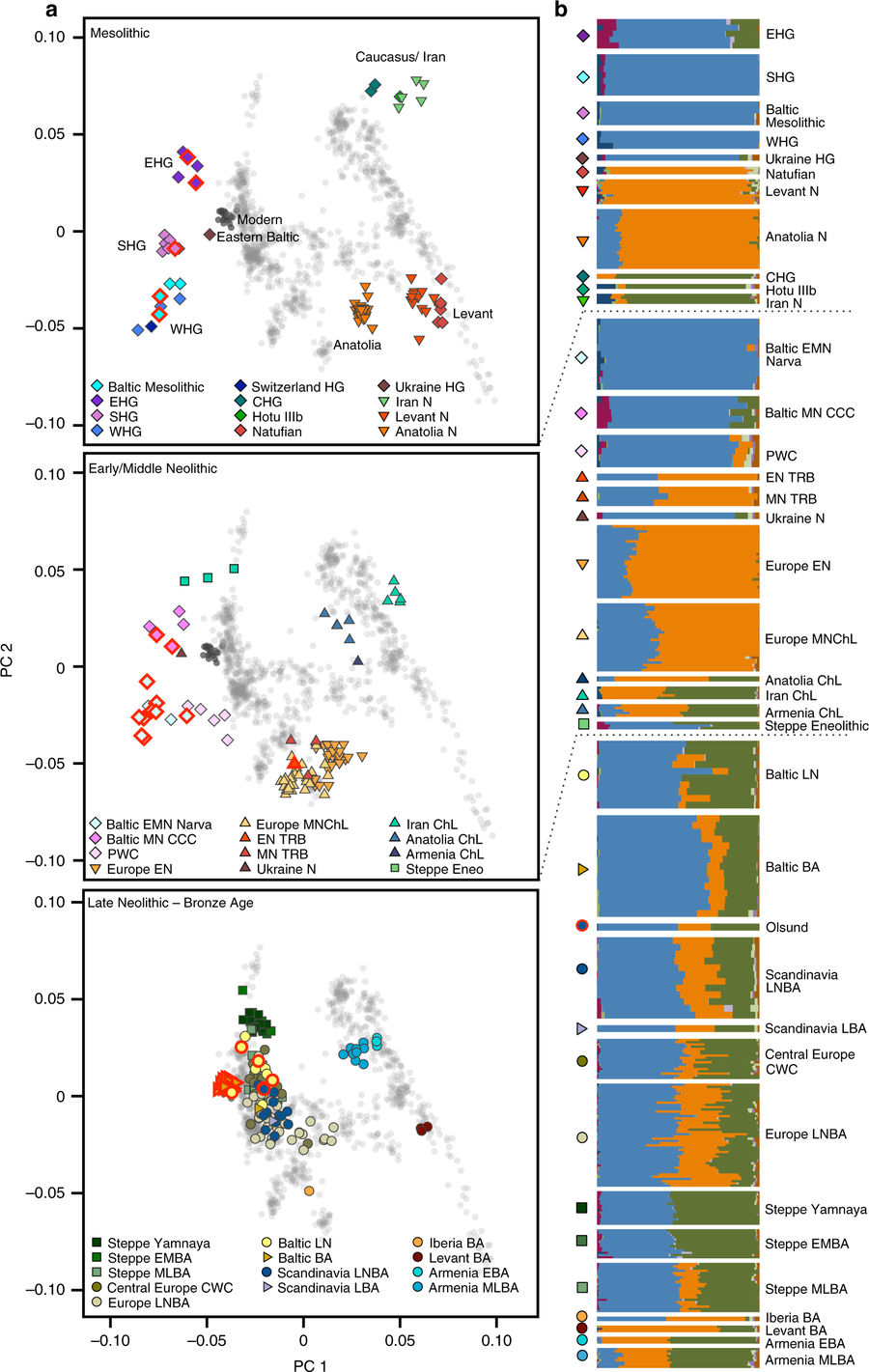

Genetic data shows a uniform picture of these communities, with exclusively CWC-derived ancestry and haplogroups. So in Mittnik et al. (2018) all Baltic samples show R1a-Z645 subclades, while the recent session on Estonian populations in ISBA 8 (see programme in PDF) clearly states that:

[Of the 24 Bronze Age samples from stone-cist graves] all 18 Bronze Age males belong to R1a.

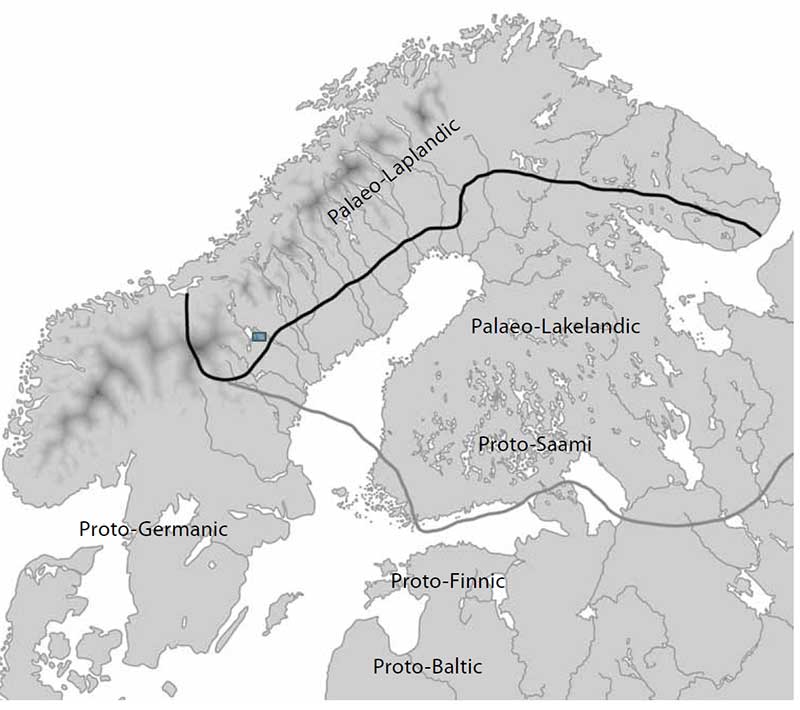

Regarding non-Uralic substrates found in Saami, supposedly absorbed during the expansion to the north (and thus representing languages spoken in northern Fennoscandia during the Bronze Age) this is what Aikio (2012) has to say:

The Saami substrate in the Finnish dialects thus reveals that also Lakeland Saami languages had a large number of vocabulary items of obscure origin. Most likely many of these words were substrate in Lakeland Saami, too, and ultimately derive from languages spoken in the region before Saami. In some cases the loan origin of these words is obvious due to their secondary Proto-Saami vowel combinations such as *ā–ë in *kāvë ‘bend; small bay’ and *šāpšë ‘whitefish’. This substrate can be called ‘Palaeo-Lakelandic’, in contrast to the ‘Palaeo-Laplandic’ substrate that is prominent in the lexicon of Lapland Saami. As the Lakeland Saami languages became extinct and only fragments of their lexicon can be reconstructed via elements preserved in Finnish place-names and dialectal vocabulary, we are not in a position to actually study the features of this Palaeo-Lakelandic substrate. Its existence, however, appears evident from the material above.

If we wanted to speculate further, based on the data we have now, it is very likely that two opposing groups will be found in the region:

A) The central Finnish group, in this hypothesis the Palaeo-Lakelandic group, made up of the descendants of the Mesolithic pioneers of the Komsa and Suomusjärvi cultures, and thus mainly Baltic HG / Scandinavian HG ancestry and haplogroups I / R1b(xM269) (see more on Scandinavian HG).

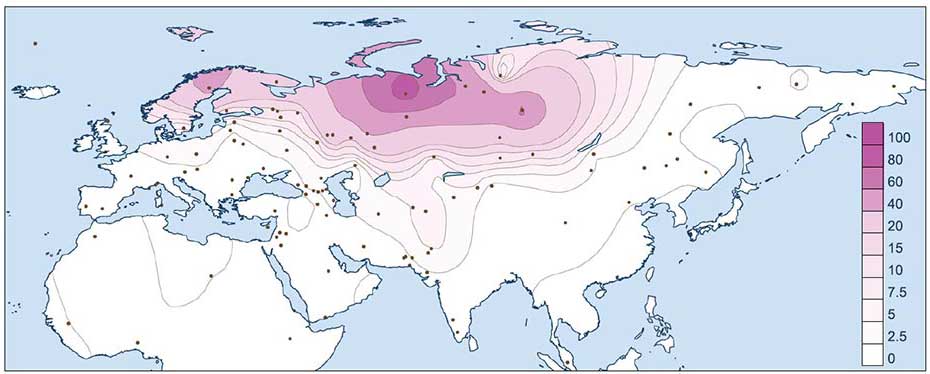

B) Lapland and Kola were probably also inhabited by similar Mesolithic populations, until it was eventually assimilated by expanding Siberian groups (of Siberian ancestry and N1c-L392 lineages) from the east – entering the region likely through the Kola peninsula – , forming the Palaeo-Laplandic group, which was in turn later replaced by expanding Proto-Saamic groups.

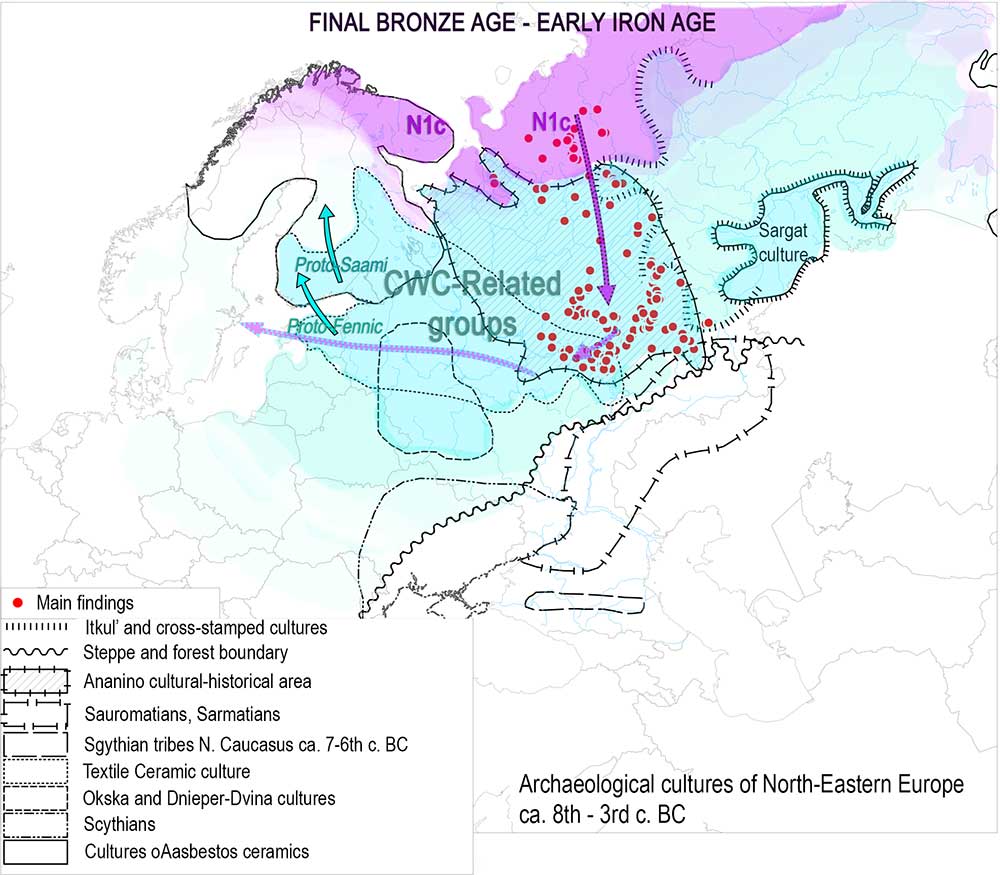

Siberian ancestry appears first in Fennoscandia at Bolshoy Oleni Ostrov ca. 1520 BC, with haplogroup N1c-L392 (2 samples, BOO002 and BOO004), and with Siberian ancestry. This is their likely movement in north-eastern Europe, from Lamnidis et al (2018):

The large Siberian component in the Bolshoy individuals from the Kola Peninsula provides the earliest direct genetic evidence for an eastern migration into this region. Such contact is well documented in archaeology, with the introduction of asbestos-mixed Lovozero ceramics during the second millenium BC, and the spread of even-based arrowheads in Lapland from 1,900 BCE. Additionally, the nearest counterparts of Vardøy ceramics, appearing in the area around 1,600-1,300 BCE, can be found on the Taymyr peninsula, much further to the east. Finally, the Imiyakhtakhskaya culture from Yakutia spread to the Kola Peninsula during the same period.

Obviously, these groups of asbestos-tempered ware are not connected to the Uralic expansion. From the same paper:

The fact that the Siberian genetic component is consistently shared among Uralic-speaking populations, with the exceptions of Hungarians and the non-Uralic speaking Russians, would make it tempting to equate this component with the spread of Uralic languages in the area. However, such a model may be overly simplistic. First, the presence of the Siberian component on the Kola Peninsula at ca. 4000 yBP predates most linguistic estimates of the spread of Uralic languages to the area. Second, as shown in our analyses, the admixture patterns found in historic and modern Uralic speakers are complex and in fact inconsistent with a single admixture event. Therefore, even if the Siberian genetic component partly spread alongside Uralic languages, it likely presented only an addition to populations carrying this component from earlier.

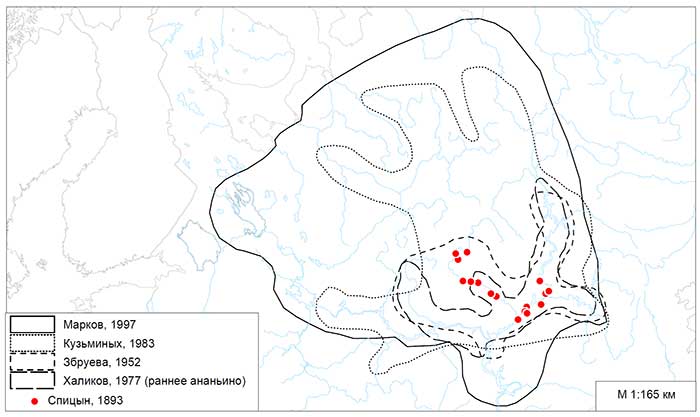

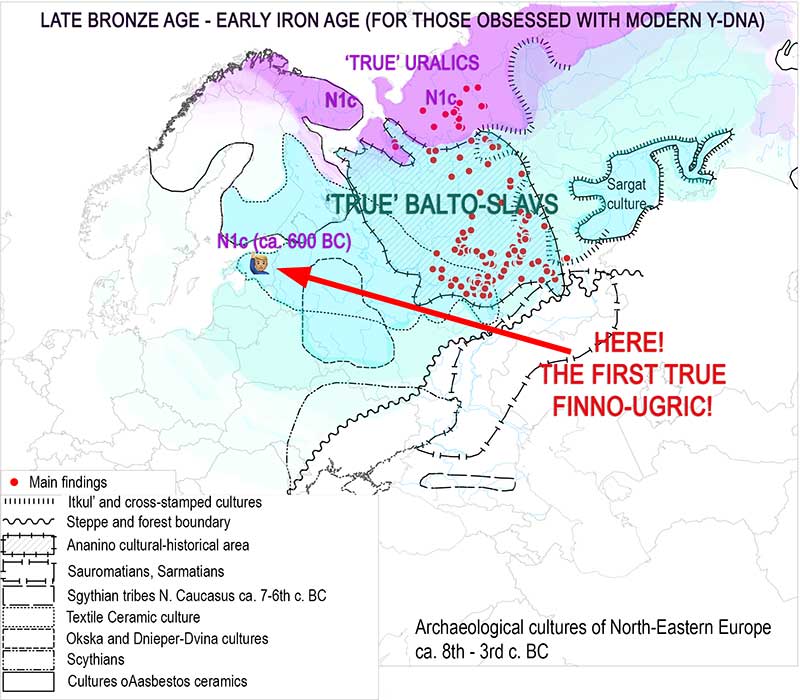

2. The Early Iron Age

The Ananino culture appears in the Vyatka-Kama area, famed for its metallurgy, with traditions similar to the North Pontic area, by this time developing Pre-Sauromatian traditions. It expanded to the north in the first half of the first millennium BC, remaining in contact with the steppes, as shown by the ‘Scythian’ nature of its material culture.

NOTE. The Ananino culture can be later followed through its zoomorphic styles into Iron Age Pjanoborskoi and Gljadenovskoi cultures, later to Ural-Siberian Middle Age cultures – Itkuska, Ust’-Poluiska, Kulaiska cultures –, which in turn can be related as prototypes of medieval Permian styles.

At the same time as the Ananino culture begins to expand ca. 1000 BC, the Netted Ware tradition from the middle Oka expanded eastwards into the Oka-Vyatka interfluve of the middle Volga region, until then occupied by the Chirkovo culture. Eventually the Akozino or Akhmylovo group (ca. 800-300 BC) emerged from the area, showing a strong cultural influence from the Ananino culture, by that time already expanding into the Cis-Urals region.

The Akozino culture remains nevertheless linked to the western Forest Zone traditions, with long-ranging influences from as far as the Lusatian culture in Poland (in metallurgical techniques), which at this point is also closely related with cultures from Scandinavia (read more on genetics of the Tollense Valley).

Different materials from Akozino reach Fennoscandia late, at the end of the Bronze Age and beginning of the Early Iron Age, precisely when the influence of the Nordic Bronze Age culture on the Gulf of Finland was declining.

This is a period when Textile ceramic cultures in north-eastern Europe evolve into well-armed chiefdom-based groups, with each chiefdom including thousands or tens of thousands, with the main settlements being hill forts, and those in Fennoscandia starting ca. 1000-400 BC.

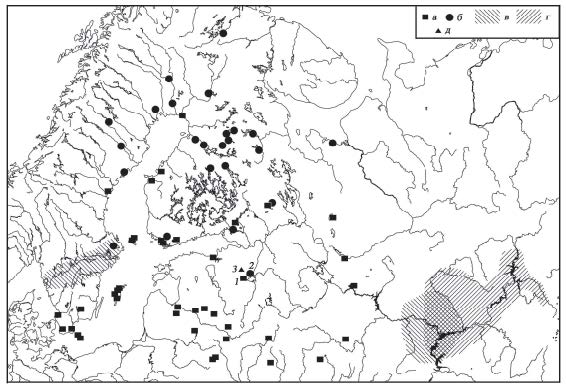

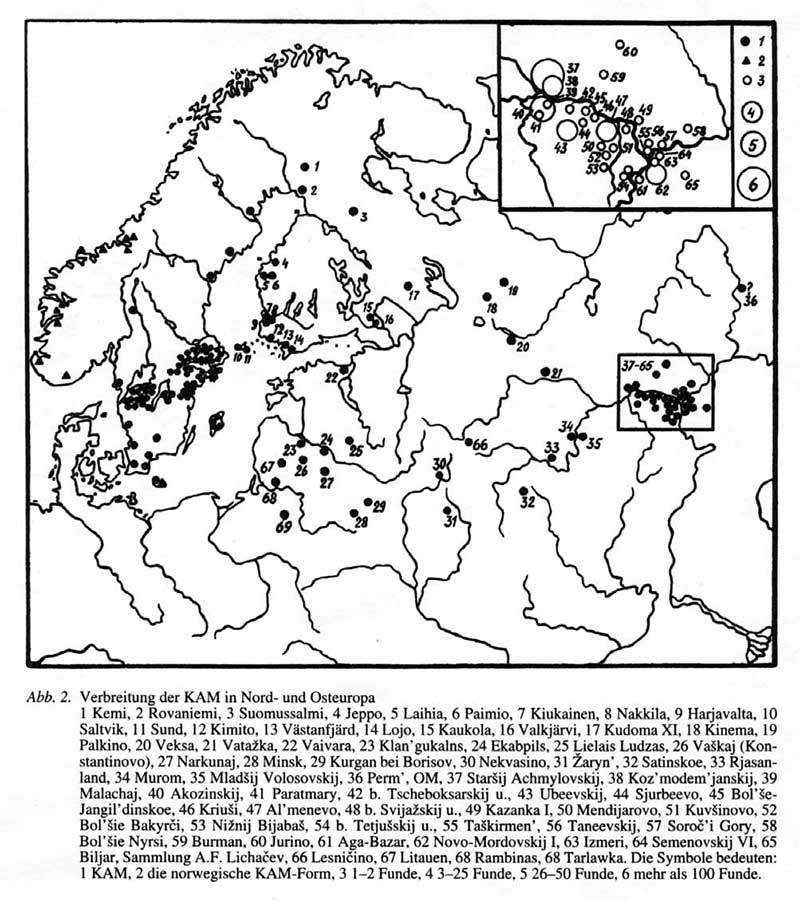

Mälar-type celts and Ananino-type celts appear simultaneously in Fennoscandia and the Forest Zone, with higher concentrations in south-eastern Sweden (Mälaren) and the Volga-Kama region, supporting the existence of a revived international trade network.

The Paimio—Asva Ware culture evolves (ca. 700-200 BC) into the Morby (in Finland) — Ilmandu syle (in Estonia, Latvia, and Mälaren) culture. The old Paimio—Asva tradition continues side by side with the new one, showing a clear technical continuity with it, but with ornamentation compared to the Early Iron Age cultures of the Upper Volga area. This new south-eastern influence is seen especially in:

- Akozino-Mälar axes (ca. 800-500 BC): introduced into the Baltic area in so great numbers – especially south-western Finland, the Åland islands, and the Mälaren area of eastern Sweden – that it is believed to be accompanied by a movement of warrior-traders of the Akozino-Akhmylovo culture, following the waterways that Vikings used more than a thousand years later. Rather than imports, they represent a copy made with local iron sources.

- Tarand graves (ca. 500 BC – AD 400): these ‘mortuary houses’ appear in the coastal areas of northern and western Estonia and the islands, at the same time as similar graves in south-western Finland, eastern Sweden, northern Latvia and Courland. Similar burials are found in Akozino-Akhmylovo, with grave goods also from the upper and middle Volga region, while grave goods show continuity with Textile ware.

The use of asbestos increases in mainland Finnish wares with Kjelmøy Ware (ca. 700 BC – AD 300), which replaced the Lovozero Ware; and in the east in inner Finland and Karelia with the Luukonsaari and Sirnihta wares (ca. 700-500 BC – AD 200), where they replaced the previous Sarsa-Tomitsa ceramics.

The Gorodets culture appears during the Scythian period in the forest-steppe zone north and west of the Volga, shows fortified settlements, and there are documented incursions of Gorodets iron makers into the Samara valley, evidenced by deposits of their typical pottery and a bloom or iron in the region.

Iron Age ethnolinguistic groups

According to (Koryakova and Epimakhov 2007):

It is commonly accepted by archaeology, ethnography, and linguistics that the ancestors of the Permian peoples (the Udmurts, Komi-Permians, and Komi-Zyryans) left the sites of Ananyino cultural intercommunity.

NOTE. For more information on the Late Metal Ages and Early Medieval situation of Finno-Ugric languages, see e.g. South-eastern contact area of Finnic languages in the light of onomastics (Rahkonen 2013).

Certain innovations shared between Proto-Fennic (identified with the Gulf of Finland) and Proto-Mordvinic (from the Gorodets culture) point to their close contact before the Proto-Fennic expansion, and thus to the identification of Gorodets as Proto-Mordvinic, hence Akozino as Volgaic (Parpola 2018):

- the noun paradigms and the form and function of individual cases,

- the geminate *mm (foreign to Proto-Uralic before the development of Fennic under Germanic influence) and other non-Uralic consonant clusters.

- the change of numeral *luka ‘ten’ with *kümmen.

- The presence of loanwords of non-Uralic origin, related to farming and trees, potentially Palaeo-European in nature (hence possibly from Siberian influence in north-eastern Europe).

The introduction of a strongly hierarchical chiefdom system can quickly change the pre-existing social order and lead to a major genetic shift within generations, without a radical change in languages, as shown in Sintashta-Potapovka compared to the preceding Poltavka society (read more about Sintashta).

Fortified settlements in the region represented in part visiting warrior-traders settled through matrimonial relationships with local chiefs, eager to get access to coveted goods and become members of a distribution network that could guarantee them even military assistance. Such a system is also seen synchronously in other cultures of the region, like the Nordic Bronze Age and Lusatian cultures (Parpola 2013).

The most likely situation is that N1c subclades were incorporated from the Circum-Artic region during the Anonino (Permic) expansion to the north, later emerged during the formation of the Akozino group (Volgaic, under Anonino influence), and these subclades in turn infiltrated among the warrior traders that spread all over Fennoscandia and the eastern Baltic (mainly among Fennic, Saamic, Germanic, and Balto-Slavic peoples), during the age of hill forts, creating alliances partially based on exogamy strategies (Parpola 2013).

Over the course of these events, no language change is necessary in any of the cultures involved, since the centre of gravity is on the expanding culture incorporating new lineages:

- first on the Middle Volga, when Ananino expands to the north, incorporatinig N1c lineages from the Circum-Artic region.

- then with the expansion of the Akozino-Akhmylovo culture into Ananino territory, admixing with part of its population;

- then on the Baltic region, when materials are imported from Akozino into Fennoscandia and the eastern Baltic (and vice versa), with local cultures being infiltrated by foreign (Akozino) warrior-traders and their materials;

- and later with the different population movements that led eventually to a greater or lesser relevance of N1c in modern Finno-Permic populations.

To argue that this infiltration and later expansion of lineages changed the language in one culture in one of these events seems unlikely. To use this argument of “opposite movement of ethnic and language change” for different successive events, and only on selected regions and cultures (and not those where the greatest genetic and cultural impact is seen, like e.g. Sweden for Akozino materials) is illogical.

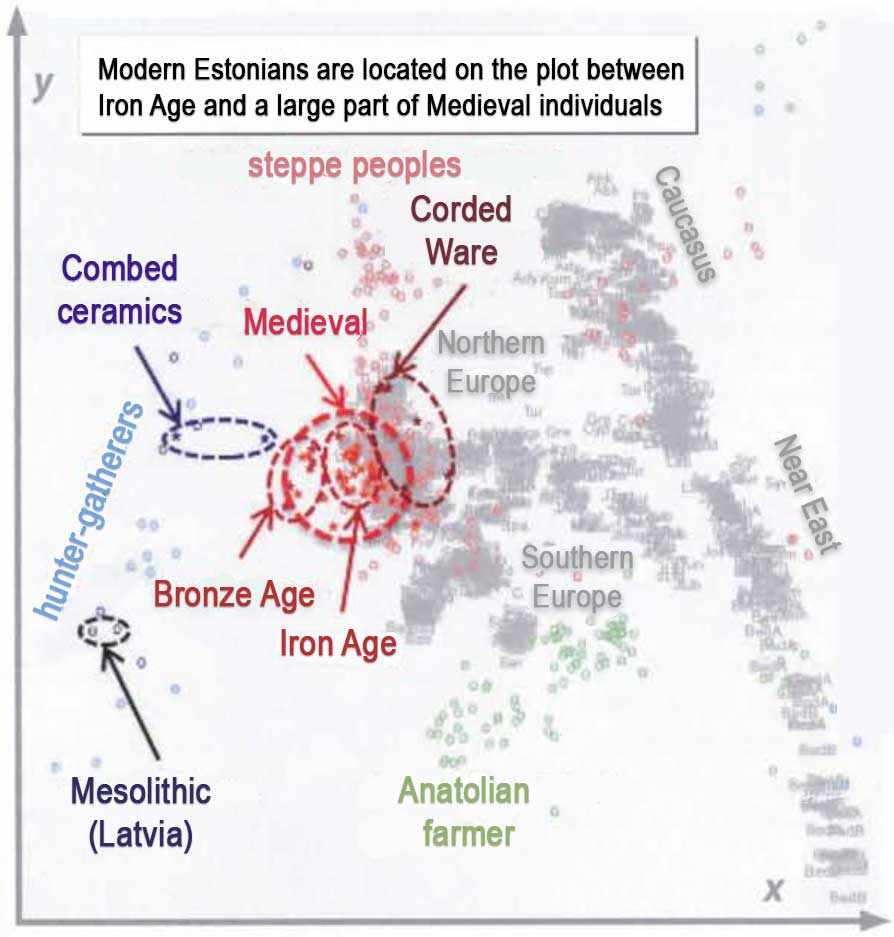

NOTE. Notice how I write here about “infiltration” and “lineages”, not “migration” or “populations”. To understand that, see below the next section on autosomal studies to compare Bronze Age, Iron Age, Medieval and Modern Estonians, and see how little the population of Estonia (homeland of Proto-Fennic and partially of Proto-Finno-Saamic) has changed since the Corded Ware migrations, suggesting genetic continuity and thus mostly close inter-regional and intra-regional contacts in the Forest Zone, hence a very limited impact of the absorbed N1c lineages (originally at some point incorporated from the Circum-Artic region). You can also check on the most recent assessment of R1a vs. N1c in modern Uralic populations.

Iron Age and later populations

From the session on Estonian samples on ISBA 8, by Tambets et al.:

[Of the 13 samples from the Iron Age tarand-graves] We found that the Iron Age individuals do in fact carry chrY hg N3 (…) Furthermore, based on their autosomal data, all of the studied individuals appear closer to hunter-gatherers and modern Estonians than Estonian CWC individuals do.

EDIT (16 OCT) A recent abstract with Saag as main author (Tambets second) cites 3 out of 5 sampled Iron Age individuals as having haplogroup N3.

EDIT (28 OCT): Notice also the appearance of N1a1a1a1a1a1a1-L1025 in Lithuania (ca. 300 AD), from Damgaard (Nature 2018); the N1c sample of the Krivichi Pskov Long Barrows culture (ca. 8th-10th c. AD), and N1a1a1a1a1a1a7-Y4341 among late Vikings from Sigtuna (ca. 10th-12th c. AD) in Krzewinska (2018).

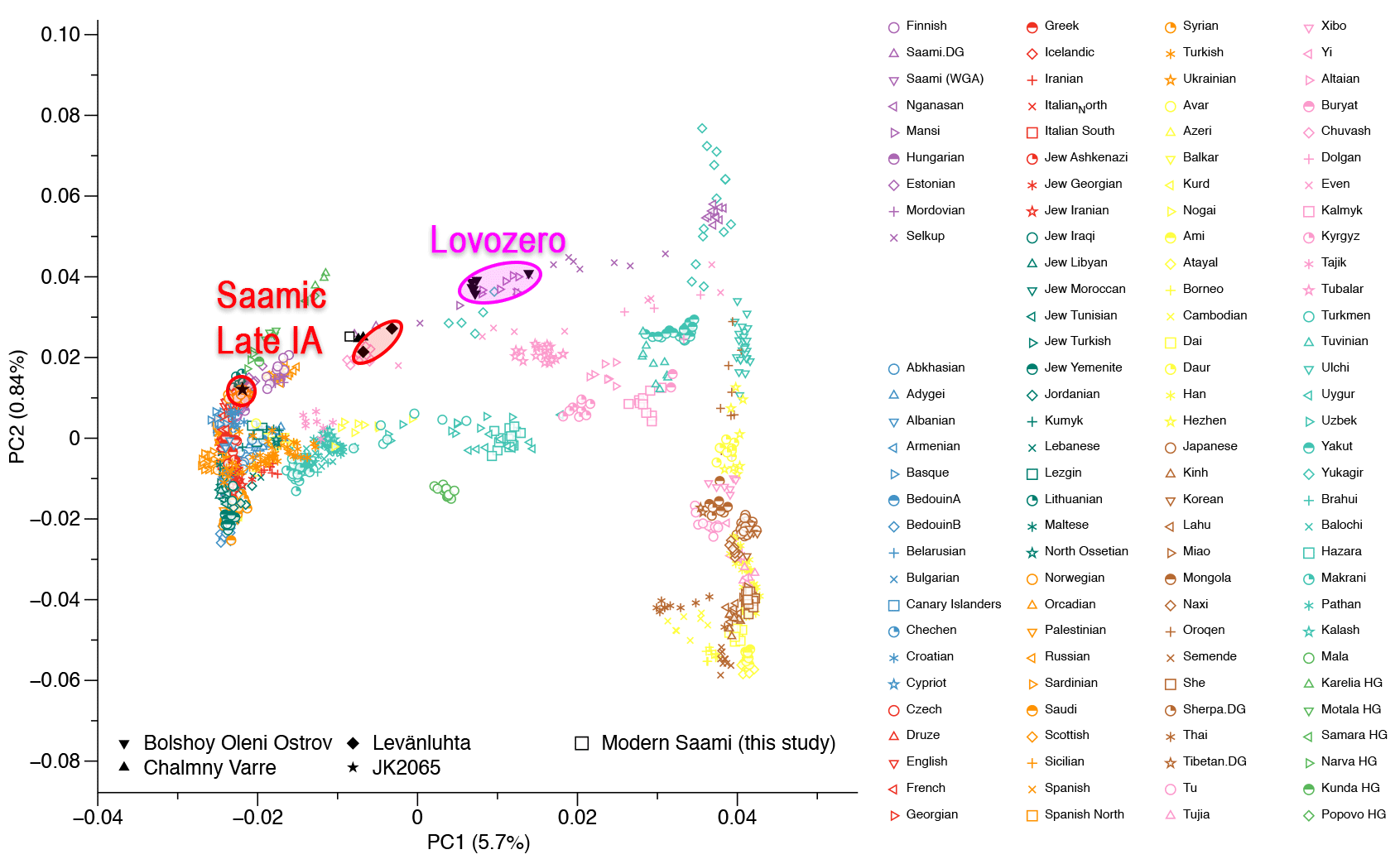

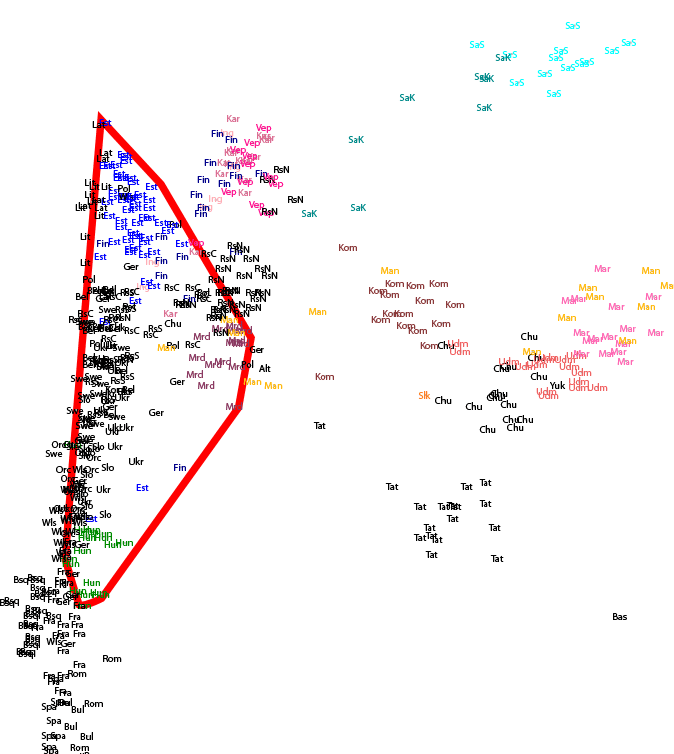

Looking at the plot, the genetic inflow marking the change from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age looks like an obvious expansion of nearby peoples with CWC-related ancestry, i.e. likely from the south-east, near the Middle Volga, where influence of steppe peoples is greater (hence likely Akozino) into a Proto-Fennic population already admixed (since the arrival of Corded Ware groups) with Comb Ware-like populations.

All of these groups were probably R1a-Z645 (likely R1a-Z283) since the expansion of Corded Ware peoples, with an introduction of some N1c lineages precisely during this Iron Age period. This infiltration of N1c-L392 with Akozino is obviously not directly related to Siberian cultures, given what we know about the autosomal description of Estonian samples.

Rather, N1c-L392 lineages were likely part of the incoming (Volgaic) Akozino warrior-traders, who settled among developing chiefdoms based on hill fort settlements of cultures all over the Baltic area, and began to appear thus in some of the new tarand graves associated with the Iron Age in north-eastern Europe.f

A good way to look at this is to realize that no new cluster appears compared to the data we already have from Baltic LN and BA samples from Mittnik et al. (2018), so the Estonian BA and IA clusters must be located (in a proper PCA) in the cline from Pit-Comb Ware culture through Baltic BA to Corded Ware groups:

This genetic continuity from Corded Ware (the most likely Proto-Uralic homeland) to the Proto-Fennic and Proto-Saamic communities in the Gulf of Finland correlates very well with the known conservatism of Finno-Saamic phonology, quite similar to Finno-Ugric, and both to Proto-Uralic (Kallio 2017): The most isolated region after the expansion of Corded Ware peoples, the Gulf of Finland, shielded against migrations for almost 1,500 years, is then the most conservative – until the arrival of Akozino influence.

NOTE. This has its parallel in the phonetic conservatism of Celtic or Italic compared to Finno-Ugric-influenced Germanic, Balto-Slavic, or Indo-Iranian.

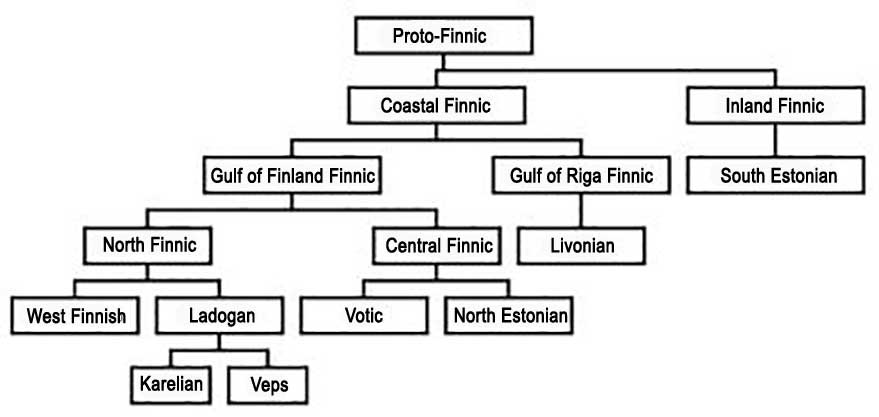

Only later would certain regions (like Finland or Lappland) suffer Y-DNA bottlenecks and further admixture events associated with population displacements and expansions, such as the spread of Fennic peoples from their Estonian homeland (evidenced by the earlier separation of South Estonian) to the north and east:

The initial Proto-Fennic expansion was probably coupled with the expansion of Proto-Saami to the north, with the Kjelmøy Ware absorbing the Siberian population of Lovozero Ware, and potentially in inner Finland and Karelia with the Luukonsaari and Sirnihta wares (Carpelan and Parpola 2017).

This Proto-Saami population expansion from the mainland to the north, admixing with Lovozero-related peoples, is clearly reflected in the late Iron Age Saamic samples from Levänluhta (ca. 400-800 AD), as a shift (of 2 out of 3 samples) to Siberian-like ancestry from their original CWC_Baltic-like situation (see PCA from Lamnidis et al. 2018 above).

Also, Volgaic and Permic populations from inner Finland and the Forest Zone to the Cis-Urals and Circum-Artic regions probably incorporate Siberian ancestry and N1c-L392 lineages during these and later population movements, while the westernmost populations – Estonian, Mordvinic – remain less admixed (see PCA from Tambets et al. 2018 below).

We also have data of N1c-L392 in Nordic territory in the Middle Ages, proving its likely strong presence in the Mälaren area since the Iron Age, with the arrival of Akozino warrior traders. Similarly, it is found among Balto-Slavic groups along the eastern Baltic area. Obviously, no language change is seen in Nordic Bronze Age and Lusatian territory, and none is expected in Estonian or Finnish territory, either.

Therefore, no “N1c-L392 + Siberian ancestry” can be seen expanding Finno-Ugric dialects, but rather different infiltrations and population movements with limited effects on ancestry and Y-DNA composition, depending on the specific period and region.

An issue never resolved

Because N1c-L392 subclades & Siberian ancestry, which appear in different proportions and with different origins among some modern Uralic peoples, do not appear in cultures supposed to host Uralic-speaking populations until the Iron Age, people keep looking into any direction to find the ‘true’ homeland of those ‘Uralic N1c peoples’? Kind of a full circular reasoning, anyone? The same is valid for R1a & steppe ancestry being followed for ‘Indo-Europeans’, or R1b-P312 & Neolithic farmer ancestry being traced for ‘Basques’, because of their distribution in modern populations.

I understand the caution of many pointing to the need to wait and see how samples after 2000 BC are like, in every single period, from the middle and upper Volga, Kama, southern Finland, and the Forest Zone between Fennoscandia and the steppe. It’s like waiting to see how people from Western Yamna and the Carpathian Basin after 3000 BC look like, to fill in what is lacking between East Yamna and Bell Beakers, and then between them and every single Late PIE dialect.

But the answer for Yamna-Bell Beaker-Poltavka peoples during the Late PIE expansion is always going to be “R1b-L23, but with R1a-Z645 nearby” (we already have a pretty good idea about that); and the answer for the Forest Zone and northern Cis- and Trans-Urals area – during the time when Uralic languages are known to have already been spoken there – is always going to be “R1a-Z645, but with haplogroup N nearby”, as is already clear from the data on the eastern Baltic region.

So, without a previously proposed model as to where those amateurs expressing concern about ‘not having enough data’ expect to find those ‘Uralic peoples’, all this waiting for the right data looks more like a waiting for N1c and Siberian ancestry to pop up somewhere in the historic Uralic-speaking area, to be able to say “There! A Uralic-speaking male!”. Not a very reasonable framework to deal with prehistoric peoples and their languages, I should think.

But, for those who want to do that, let me break the news to you already:

And here it is, an appropriate fantasy description of the ethnolinguistic groups from the region. You are welcome:

- During the Bronze Age, late Corded Ware groups evolve as the western Textile ware

FennicBalto-Slavic group in the Gulf of Finland; the Netted WareSaamicBalto-Slavic group of inner Finland; the south Netted Ware / AkozinoVolgaicBalto-Slavic groups of the Middle Volga; and the AnoninoPermicBalto-Slavic group in the north-eastern Forest Zone; all developing still in close contact with each other, allowing for common traits to permeate dialects. - These Balto-Slavic groups would then incorporate west of the Urals during and after the Iron Age (ca. 800-500 BC first, and also later during their expansion to the north) limited ancestry and lineages from eastern European hunter-gatherer groups of

Palaeo-EuropeanFennic andPalaeo-SiberianVolgaic and Permic languages from the Circum-Artic region, but they adopted nevertheless the language of the newcomers in every single infiltration of N1c lineages and/or admixture with Siberian ancestry. Oh and don’t forget the Saamic peoples from central Sweden, of course, the famous N1c-L392 ‘Rurikid’ lineages expanding Saamic to the north and replacing Proto-Germanic…

The current model for those obsessed with modern Y-DNA is, therefore, that expanding Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age cultures from north-eastern Europe adopted the languages of certain lineages originally from sub-Neolithic (Scandinavian and Siberian) hunter-gatherer populations of the Circum-Artic region; lineages that these cultures incorporated unevenly during their expansions. Hmmmm… Sounds like an inverse Western movie, where expanding Americans end up speaking Apache, and the eastern coast speaks Spanish until Italian migrants arrive and make everyone speak English… or something. A logic, no-nonsense approach to ethnolinguistic identification.

I kid you not, this is the kind of models we are going to see very soon. In 2018 and 2019, with ancient DNA able to confirm or reject archaeological hypotheses based on linguistic data, people will keep instead creating new pet theories to support preconceived ideas based on the Y-DNA prevalent among modern populations. That is, information available in the 2000s.

So what’s (so much published) ancient DNA useful for, exactly?

[Next post on the subject: Corded Ware—Uralic (III): Seima-Turbino and the Ugric and Samoyedic expansion]

See also

- Uralic speakers formed clines of Corded Ware ancestry with WHG:ANE

- Magyar tribes brought R1a-Z645, I2a-L621, and N1a-L392(xB197) lineages to the Carpathian Basin

- R1a-Z280 and R1a-Z93 shared by ancient Finno-Ugric populations; N1c-Tat expanded with Micro-Altaic

Related

- Corded Ware—Uralic (I): Differences and similarities with Yamna

- Haplogroup R1a and CWC ancestry predominate in Fennic, Ugric, and Samoyedic groups

- The Iron Age expansion of Southern Siberian groups and ancestry with Scythians

- Evolution of Steppe, Neolithic, and Siberian ancestry in Eurasia (ISBA 8, 19th Sep)

- Mitogenomes from Avar nomadic elite show Inner Asian origin

- On the origin and spread of haplogroup R1a-Z645 from eastern Europe

- Oldest N1c1a1a-L392 samples and Siberian ancestry in Bronze Age Fennoscandia

- Consequences of Damgaard et al. 2018 (III): Proto-Finno-Ugric & Proto-Indo-Iranian in the North Caspian region

- The concept of “Outlier” in Human Ancestry (III): Late Neolithic samples from the Baltic region and origins of the Corded Ware culture

- Genetic prehistory of the Baltic Sea region and Y-DNA: Corded Ware and R1a-Z645, Bronze Age and N1c

- More evidence on the recent arrival of haplogroup N and gradual replacement of R1a lineages in North-Eastern Europe

- Another hint at the role of Corded Ware peoples in spreading Uralic languages into north-eastern Europe, found in mtDNA analysis of the Finnish population

- New Ukraine Eneolithic sample from late Sredni Stog, near homeland of the Corded Ware culture