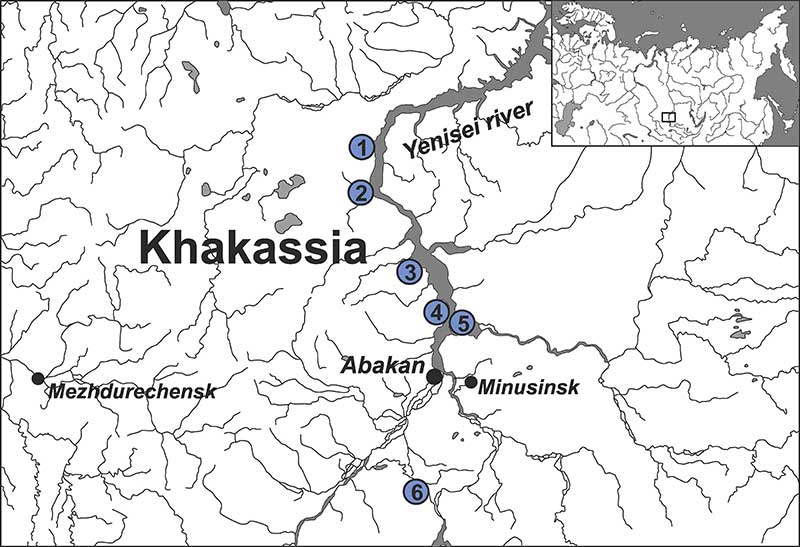

Maternal genetic features of the Iron Age Tagar population from Southern Siberia (1st millennium BC), by Pilipenko et al. (2018).

Interesting excerpts (emphasis mine):

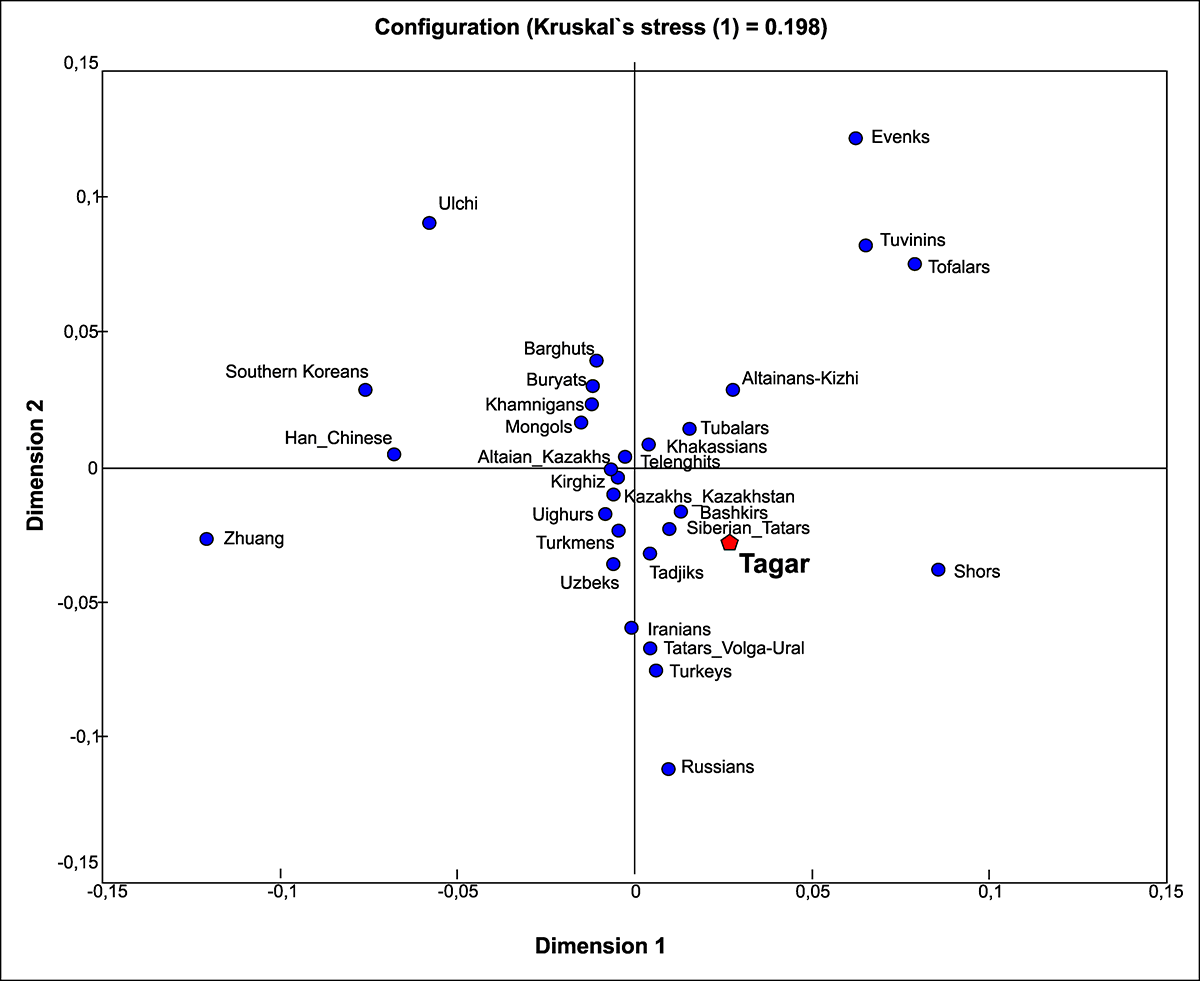

The positions of non-Tagar Iron Age groups in the MDS plot were correlated with their geographic position within the Eurasian steppe belt and with frequencies of Western and Eastern Eurasian mtDNA lineages in their gene pools. Series from chronological Tagar stages (similar to the overall Tagar series) were located within the genetic variability (in terms of mtDNA) of Scythian World nomadic groups (Figs 5 and 6; S4 and S6 Tables). Specifically, the Early Tagar series was more similar to western nomads (North Pontic Scythians), while the Middle Tagar was more similar to the Southern Siberian populations of the Scythian period. The Late Tagar group (Tes`culture) belonging to the Early Xiongnu period had the “western-most” location on the MDS plot with the maximal genetic difference from Xiongnu and other eastern nomadic groups (but see Discussion concerning the low sample size for the Tes`series).

In a comparison of our Tagar series with modern populations in Eurasia, we detected similarity between the Tagar group and some modern Turkic-speaking populations (with the exception of the Indo-Iranian Tajik population) (Fig 7; S2 Table). Among the modern Turkic-speaking groups, populations from the western part of the Eurasian steppe belt, such as Bashkirs from the Volga-Ural region and Siberian Tatars from the West Siberian forest-steppe zone, were more similar to the Tagar group than modern Turkic-speaking populations of the Altay-Sayan mountain system (including the Khakassians from the Minusinsk basin) (Fig 7).

Mitochondrial DNA diversity and genetic relationships of the Tagar population

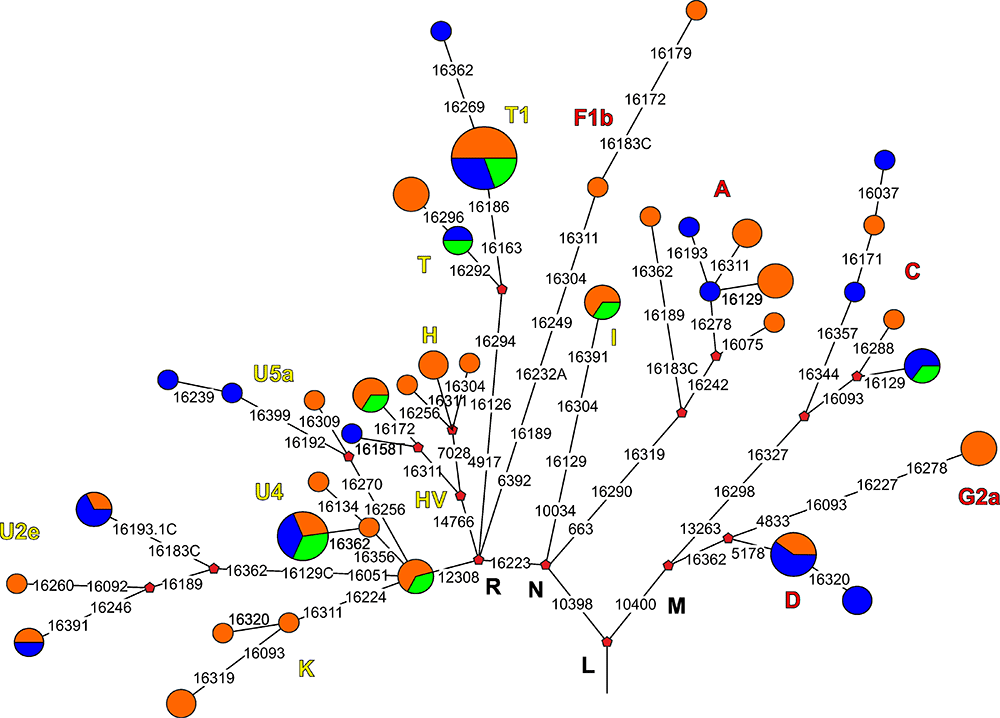

Our results are not inconsistent with the assumption of a probable role of gene flow due to the migration from Western Eurasia to the Minusinsk basin in the Bronze Age in the formation of the genetic composition of the Tagar population. Particularly, we detected many mtDNA lineages/clusters with probable West Eurasian origin that were dominant in modern populations of different parts of Europe, Caucasus, and the Near East (such as K and HV6) in our Tagar series based on a phylogeographic analysis.

We detected relatively low genetic distances between our Tagar population and two Bronze Age populations from the Minusinsk basin—the Okunevo culture population (pre-Andronovo Bronze Age) and Andronovo culture population, followed by Afanasievo population from the Minusinsk Basin and Middle Bronze Age population from the Mongolian Altai Mountains (the region adjacent to the Minusinsk basin) (Figs 3 and 6; S3 and S5 Tables). Among West Eurasian part of our Tagar series we also observed haplogroups/sub-haplogroups and haplotypes shared with Early and Middle Bronze Age populations from Minusinsk Basin and western part of Eurasian steppe belt (Fig 4; S5 Table). Thus, our results suggested a potentially significant role of the genetic components, introduced by migrants from Western Eurasia during the Bronze Age, in the formation of the genetic composition of the Tagar population. It is necessary to note the relatively small size of available mtDNA samples from the Bronze Age populations of Minusinsk basin; accordingly, additional mtDNA data for these populations are required to further confirm our inference.

Another substantial part of the mtDNA pool of the Tagar and other eastern populations of the Scythian World is typical of populations in Southern Siberia and adjacent regions of Central Asia (autochthonous Central Asian mtDNA clusters). Most of these components belong to the East Eurasian cluster of mtDNA haplogroups. Moreover, the role of each of these components in the formation of the genetic composition of subsequent (to the present) populations in South Siberia and Central Asia could be very different. In this regard, cluster C4a2a (and its subcluster C4a2a1), and haplogroup A8 are of particular interest.

Genetic features of successive Tagar groups

We compared successive Tagar groups (Early, Middle, and Late Tagar) with each other and with other Iron Age nomadic populations to evaluate changes in the mtDNA pool structure. Despite the genetic similarity between the Early and Middle Tagar series and Scythian World nomadic groups (Figs 5 and 6; S4 and S6 Tables), there were some peculiarities. For example, the Early Tagar series was more similar to North Pontic Classic Scythians, while the Middle Tagar samples were more similar to the Southern Siberian populations of the Scythian period (i.e., completely synchronous populations of regions neighboring the Minusinsk basin, such as the Pazyryk population from the Altay Mountains and Aldy-Bel population from Tuva).

We observed differences in the mtDNA pool structure between the Early and the Middle chronological stages of the Tagar culture population, as evidenced by the change in the ratio of Western to Eastern Eurasian mtDNA components. The contribution of Eastern Eurasian lineages increased from about one-third (34.8%) in the Early Tagar group to almost one-half (45.8%) in the Middle Tagar group.

At the level of mtDNA haplogroups, we detected a decrease in the diversity of phylogenetic clusters during the transition from the Early Tagar to the Middle Tagar. This decline in diversity equally affected the West Eurasian and East Eurasian components of the Tagar mtDNA pool. It should be noted that this decrease can be partially explained by the smaller number of Middle Tagar than Early Tagar samples. Under a simple binomial approximation the mtDNA clusters, observed at frequencies of 6.3% and 11.7%, could be lost by chance in our Early (N = 46) and Middle (N = 24) Tagar samples, respectively. However, the simultaneous lack of several such clusters, with a total frequency in the gene pool of the Early group of 34.8%, is unlikely.

The observed reduction in the genetic distance between the Middle Tagar population and other Scythian-like populations of Southern Siberia(Fig 5; S4 Table), in our opinion, is primarily associated with an increase in the role of East Eurasian mtDNA lineages in the gene pool (up to nearly half of the gene pool) and a substantial increase in the joint frequency of haplogroups C and D (from 8.7% in the Early Tagar series to 37.5% in the Middle Tagar series). These features are characteristic of many ancient and modern populations of Southern Siberia and adjacent regions of Central Asia, including the Pazyryk population of the Altai Mountains. We did not obtain strong evidence for an intensification of genetic contact between the population of the Minusinsk basin and the Altai Mountains in the Middle Tagar period compared with the Early Tagar period. Although, several archaeologists have found evidence for the intensification of contact at the level of material culture, namely, a cultural influence of the population of the Altai Mountains (represented by the Pazyryk population) on the population of the Minusinsk basin (the Saragash Tagar group) [6, 71, 72].

Another important issue is the change in the genetic structure of the Tagar population during the transition from the Middle (Saragash) to the Late (Tes`) stage. The Late Tagar stage refers to the Xiongnu period. Many archaeologists suggest that the formation of the Tes`stage involved the direct cultural influence of the Xiongnu and/or related groups of nomads from more eastern regions of Central Asia [71, 73]. Some archaeologists have even suggested renaming the Tes`stage in the Tes`culture [71], emphasizing the role of new eastern cultural elements. If this influence also existed at the genetic level, then we would expect to observe new genetic elements in the Tes`gene pool, particularly those of East Eurasian origin.

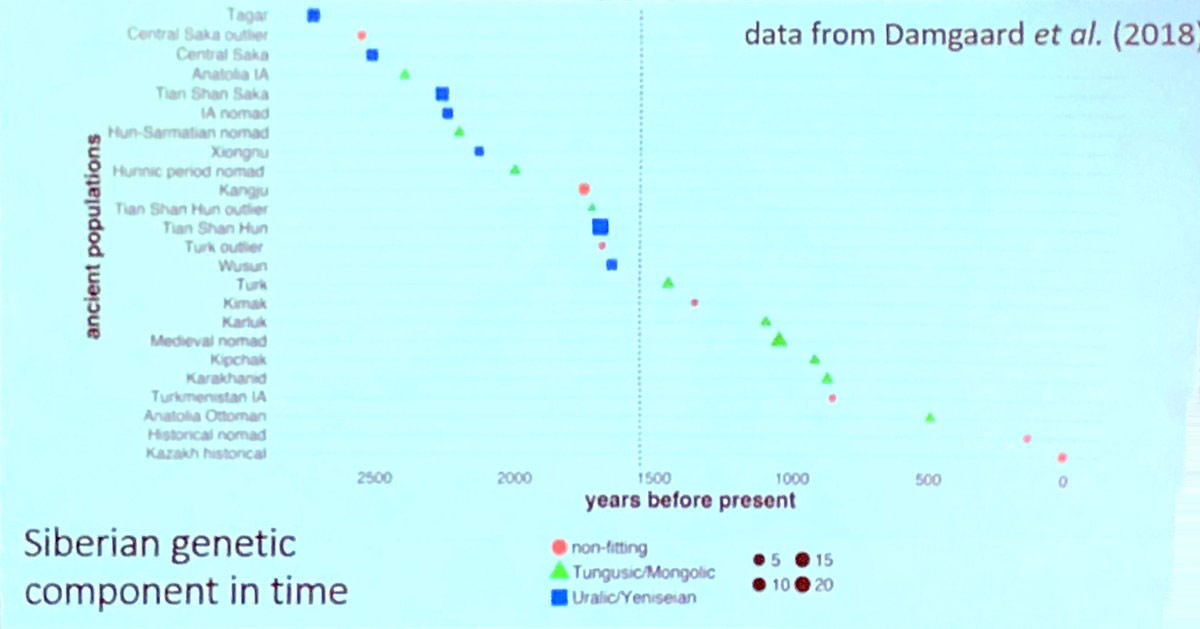

Siberian ancestry

Just a reminder of the recent session in ISBA 8 on expanding Scythians (and also Mongolians and Turks) spreading Siberian ancestry, usually (wrongly) identified as “Uralic-Yeniseian” based on modern populations (similar to how steppe ancestry is wrongly identified as “Indo-European”), see the following graphic including the Tagar population:

And also the poster by Alexander M. Kim et al. Yeniseian hypotheses in light of genome-wide ancient DNA from historical Siberia:

The relevance of ancient DNA data to debates in historical linguistics is an emphatic strand in much recent work on the archaeogenetics of Eurasia, where the discussion has focused heavily on Indo-European (Haak et al. 2015; Narasimhan et al. 2018; de Barros Damgaard et al. 2018a,b). We present new genome-wide ancient DNA data from a historical Siberian individual in relation to Yeniseian, an isolated language “microfamily” (Vajda 2014) that nonetheless sits at the center of numerous controversial proposals in historical linguistics and cultural interaction. Yeniseian’s sole surviving representative is Ket, a critically endangered language fluently spoken by only a few dozen individuals near the Middle Yenisei River of Central Siberia.

In strong contrast to the present-day picture, river names and argued substrate influences and loanwords in languages outside the current range of Yeniseian, as well as direct records from the Russian colonial period, indicate that speakers of extinct Yeniseian languages had a formerly much broader presence in the taiga of Central Siberia as well as further south in the mountainous Altai-Sayan region – and perhaps even further afield in Inner Asia (Vajda 2010; Gorbachov 2017; Blažek 2016). The consilience of these proposals with genetic data is not straightforward (Flegontov et al. 2015, 2017) and faces a major obstacle in the lack of genetic information from verifiable speakers of Yeniseian languages other than the Kets, who have had complex ongoing interactions with speakers of non-Yeniseian languages such as the Samoyedic Selkups. We attempt to remedy this with new historical Siberian aDNA data, orienting our search for common denominators and systematic difference in a broader landscape of concordance, discordance, and uncertainty at the interface of diachronic linguistics and genetics.

Related

- Evolution of Steppe, Neolithic, and Siberian ancestry in Eurasia (ISBA 8, 19th Sep)

- Mitogenomes from Avar nomadic elite show Inner Asian origin

- On the origin and spread of haplogroup R1a-Z645 from eastern Europe

- Oldest N1c1a1a-L392 samples and Siberian ancestry in Bronze Age Fennoscandia

- Consequences of Damgaard et al. 2018 (III): Proto-Finno-Ugric & Proto-Indo-Iranian in the North Caspian region

- The concept of “Outlier” in Human Ancestry (III): Late Neolithic samples from the Baltic region and origins of the Corded Ware culture

- Genetic prehistory of the Baltic Sea region and Y-DNA: Corded Ware and R1a-Z645, Bronze Age and N1c

- More evidence on the recent arrival of haplogroup N and gradual replacement of R1a lineages in North-Eastern Europe

- Another hint at the role of Corded Ware peoples in spreading Uralic languages into north-eastern Europe, found in mtDNA analysis of the Finnish population

- New Ukraine Eneolithic sample from late Sredni Stog, near homeland of the Corded Ware culture