This is the first of four posts on the Corded Ware—Uralic identification:

- Corded Ware—Uralic (I): Differences and similarities with Yamna

- Corded Ware—Uralic (II): Finno-Permic and the expansion of N-L392/Siberian ancestry

- Corded Ware—Uralic (III): “Siberian ancestry” and Ugric-Samoyedic expansions

- Corded Ware—Uralic (IV): Haplogroups R1a and N in Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic

I was reading The Bronze Age Landscape in the Russian Steppes: The Samara Valley Project (2016), and I was really surprised to find the following excerpt by David W. Anthony:

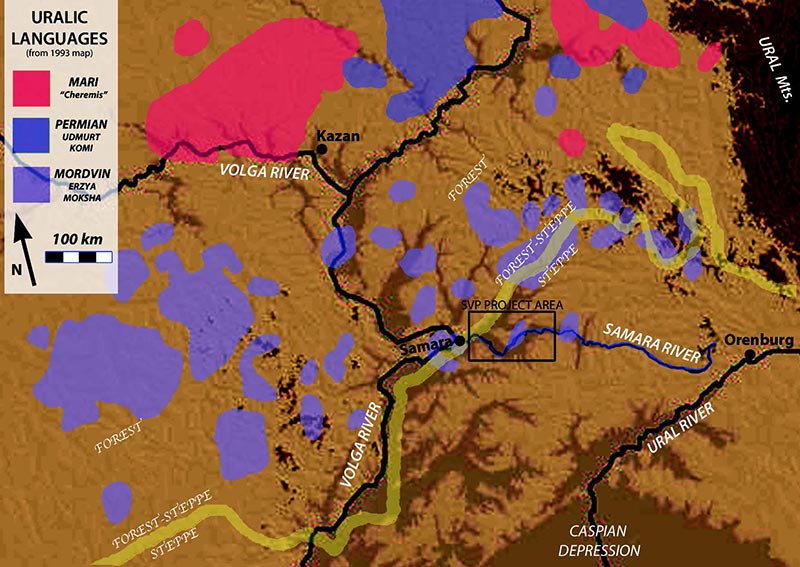

The Samara Valley links the central steppes with the western steppes and is a north-south ecotone between the pastoral steppes to the south and the forest-steppe zone to the north [see figure below]. The economic contrast between pastoral steppe subsistence, with its associated social organizations, and forest-zone hunting and fishing economies probably explains the shifting but persistent linguistic border between forest-zone Uralic languages to the north (today largely displaced by Russian) and a sequence of steppe languages to the south, recently Turkic, before that Iranian, and before that probably an eastern dialect of Proto-Indo-European (Anthony 2007). The Samara Valley represents several kinds of borders, linguistic, cultural, and ecological, and it is centrally located in the Eurasian steppes, making it a critical place to examine the development of Eurasian steppe pastoralism.

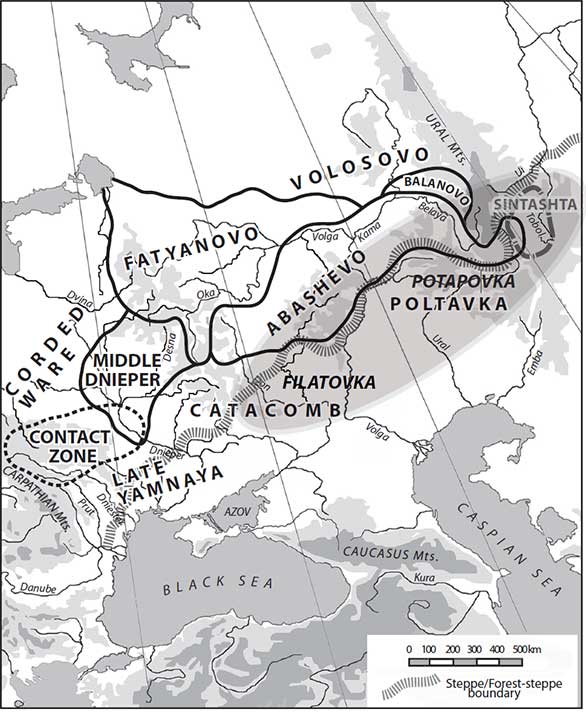

Khokhlov (translated by Anthony) further insists on the racial and ethnic divide between both populations, Abashevo to the north, and Poltavka to the south, during the formation of the Abashevo – Sintashta-Potapovka community that gave rise to Proto-Indo-Iranians:

Among all cranial series in the Volga-Ural region, the Potapovka population represents the clearest example of race mixing and probably ethnic mixing as well. The cultural advancements seen in this period might perhaps have been the result of the mixing of heterogeneous groups. Such a craniometric observation is to some extent consistent with the view of some archaeologists that the Sintashta monuments represent a combination of various cultures (principally Abashevo and Poltavka, but with other influences) and therefore do not correspond to the basic concept of an archaeological culture (Kuzmina 2003:76). Under this option, the Potapovka-Sintashta burial rite may be considered, first, a combination of traits to guarantee the afterlife of a selected part of a heterogeneous population. Second, it reflected a kind of social “caste” rather than a single population. In our view, the decisive element in shaping the ethnic structure of the Potapovka-Sintashta monuments was their extensive mobility over a fairly large geographic area. They obtained knowledge of various cultures from the populations with whom they interacted.

Interesting is also this excerpt about the predominant population in the Abashevo – Sintashta-Potapovka admixture (which supports what Chetan said recently, although this does not seemed backed by Y-DNA haplogroups found in the richest burials), coupled with the sign of incoming “Uraloid” peoples from the east, found in both Sintashta and eastern Abashevo:

The socially dominant anthropological component was Europeoid, possibly the descendants of Yamnaya. The association of craniofacial types with archaeological cultures in this period is difficult, primarily because of the small amount of published anthropological material of the cultures of steppe and forest belt (Balanbash, Vol’sko-Lbishche) and the eastern and southern steppes (Botai-Tersek). The crania associated with late MBA western Abashevo groups in the Don-Volga forest zone were different from eastern Abashevo in the Urals, where the expression of the Old Uraloid craniological complex was increased. Old Uraloid is found also on a single skull of Vol’sko-Lbishche culture (Tamar Utkul VII, Kurgan 4). Potentially related variants, including Mongoloid features, could be found among the Seima-Turbino tribes of the forest-steppe zone, who mixed with Sintashta and Abashevo. In the Sintashta Bulanova cemetery from the western Urals, some individuals were buried with implements of Seima-Turbino type (Khalyapin 2001; Khokhlov 2009; Khokhlov and Kitov 2009). Previously, similarities were noted between some individual skulls from Potapovka I and burials of the much older Botai culture in northern Kazakhstan (Khokhlov 2000a). Botai-Tersek is, in fact, a growing contender for the source of some “eastern” cranial features.

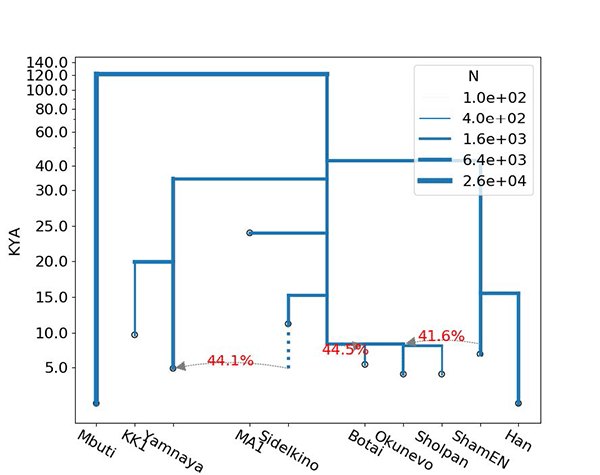

The wave of peoples associated with “eastern” features can be seen in genetics in the Sintashta outliers from Narasimhan et al. (2018), and it probably will be eventually seen in Abashevo, too. These may be related to the Seima-Turbino international network – but most likely it is directly connected to Sintashta through the starting Andronovo and Seima-Turbino horizons, by admixing of prospective groups and small-scale back-migrations.

Corded Ware – Yamna similarities?

So, if peoples of north-eastern Europe have been assumed for a long time to be Uralic speakers, what is happening with the Corded Ware = IE obsession? Is it Gimbutas’ ghost possessing old archaeologists? Probably not.

It is about certain cultural similarities evident at first sight, which have been traditionally interpreted as a sign of cultural diffusion or migration. Not dissimilar to the many Bell Beaker models available, where each archaeologist is pushing certain differences, mixing what seemed reasonable, what still might seem reasonable, and what certainly isn’t anymore after the latest ancient DNA data.

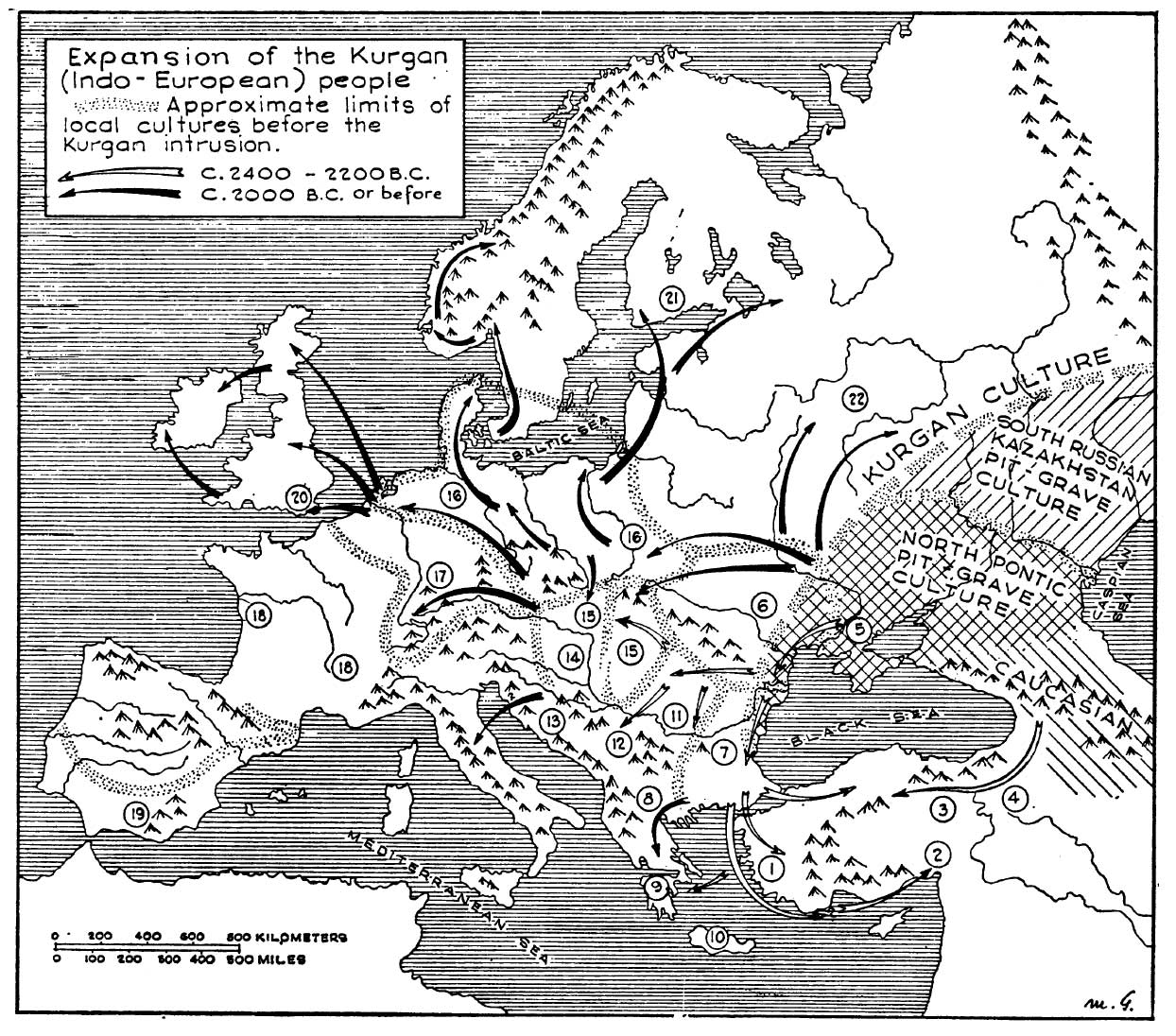

The initial models of Gimbutas, Kristiansen, or Anthony – which are known to many today – were enunciated in the infancy of archaeological studies in the regions, during and just after the fall of the USSR, and before many radiocarbon dates that we have today were published (with radiocarbon dating being still today in need of refinement), so it is only logical that gross mistakes were made.

We have similar gross mistakes related to the origins of Bell Beakers, and studying them was certainly easier than studying eastern data.

- Gimbutas believed – based mainly on Kurgan-like burials – that Bell Beaker formed from a combination of Yamna settlers with the Vučedol culture, so she was not that far from the truth.

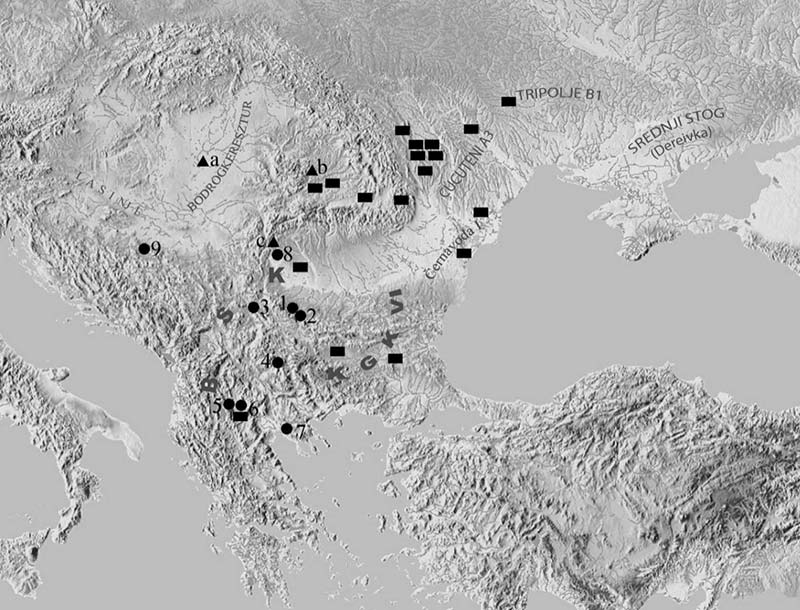

- The expansion of Corded Ware from peoples of the North Pontic forest-steppe area, proposed by Gimbutas and later supported also by Kristiansen (1989) as the main Indo-European expansion – , is probably also right about the approximate origins of the culture. Only its ‘Indo-European’ nature is in question, given the differences with Khvalynsk and Yamna evolution.

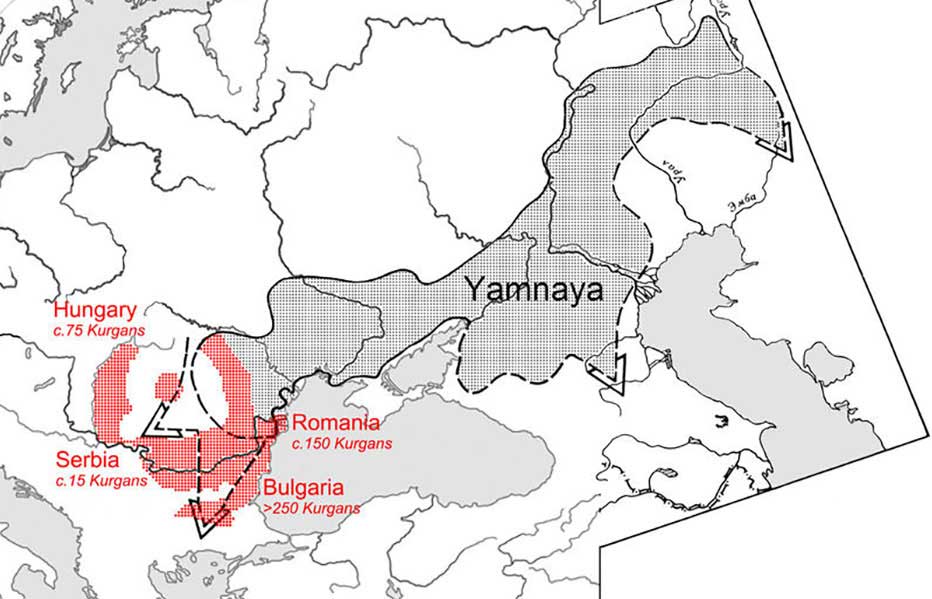

- Anthony only claimed that Yamna migrants settled in the Balkans and along the Danube into the Hungarian steppes. He never said that Corded Ware was a Yamna offshoot until after the first genetic papers of 2015 (read about his newest proposal). He initially claimed that only certain neighbouring Corded Ware groups “adopted” Indo-European (through cultural diffusion) because of ‘patron-client’ relationships, and was never preoccupied with the fate of Corded Ware and related cultures in the east European forest zone and Finland.

So none of them was really that far from the true picture; we might say a lot people are more way off the real picture today than the picture these three researchers helped create in the 1990s and 2000s. Genetics is just putting the last nail in the coffin of Corded Ware as a Yamna offshoot, instead of – as we believed in the 2000s – to Vučedol and Bell Beaker.

So let’s revise some of these traditional links between Corded Ware and Yamna with today’s data:

Archaeology

Even more than genetics – at least until we have an adequate regional and temporary sampling – , archaeological findings lead what we have to know about both cultures.

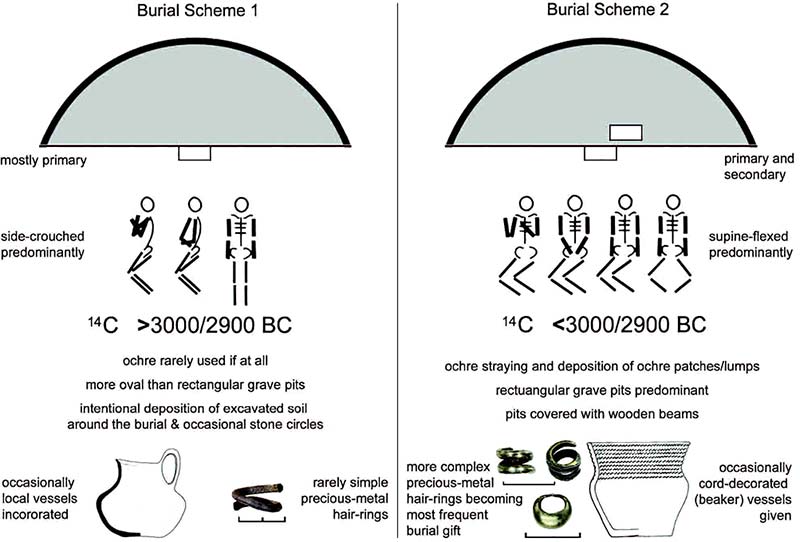

It is essential to remember that Corded Ware, starting ca. 3000/2900 BC in east-central Europe, has been proposed to be derived from Early Yamna, which appeared suddenly in the Pontic-Caspian steppes ca. 3300 BC (probably from the late Repin expansion), and expanded to the west ca. 3000.

Early Yamna is in turn identified as the expanding Late Proto-Indo-European community, which has been confirmed with the recent data on Afanasevo, Bell Beaker, and Sintashta-Potapovka and derived cultures.

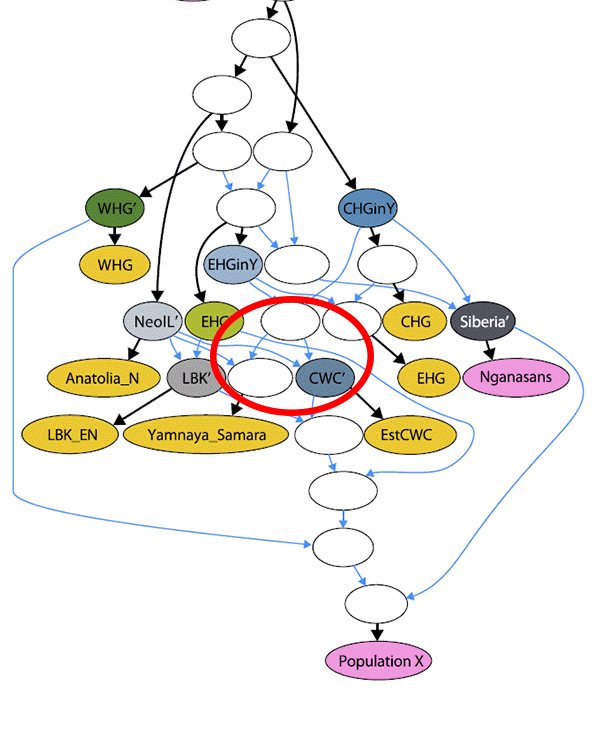

The question at hand, therefore, is if Corded Ware can be considered an offshoot of the Late PIE community, and thus whether the CWC ethnolinguistic community – proven in genetics to be quite homogeneous – spoke a Late PIE dialect, or if – alternatively – it is derived from other neighbouring cultures of the North Pontic region.

NOTE. The interpretation of an Indo-Slavonic group represented by a previous branching off of the group is untenable with today’s data, since Indo-Slavonic – for those who support it – would itself be a branch of Graeco-Aryan, and Palaeo-Balkan languages expanded most likely with West Yamna (i.e. R1b-L23, mainly R1b-Z2103) to the south.

The convoluted alternative explanation would be that Corded Ware represents an earlier, Middle PIE branch (somehow carrying R1a??) which influences expanding Late PIE dialects; this has been recently supported by Kortlandt, although this simplistic picture also fails to explain the Uralic problem.

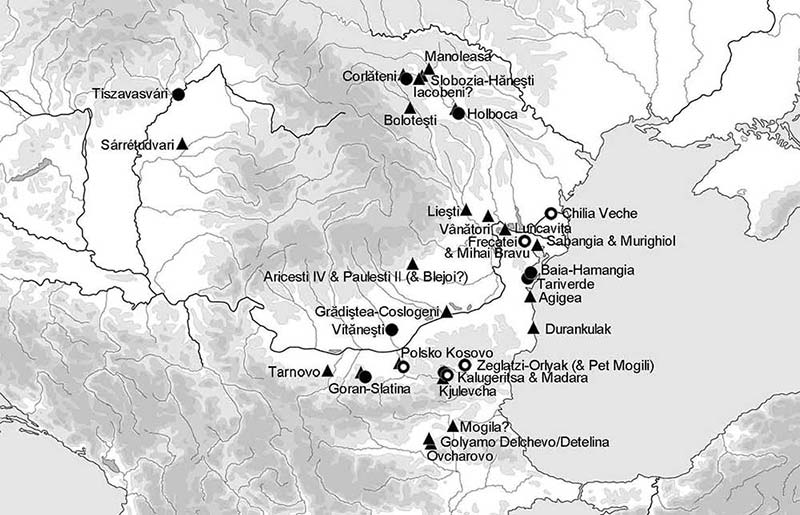

❔ Kurgans: The Yamna tradition was inherited from late Repin, in turn inherited from Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka proto-Kurgans. As for the CWC tradition, it is unclear if the tumuli were built as a tradition inherited from North and West Pontic cultures (in turn inherited or copied from Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka), such as late Trypillia, late Kvityana, late Dereivka, late Sredni Stog; or if they were built because of the spread of the ‘Transformation of Europe’, set in motion by the Early Yamna expansion ca. 3300-3000 BC (as found in east-central European cultures like Coţofeni, Lizevile, Șoimuș, or the Adriatic Vučedol). My guess is that it inherits an older tradition than Yamna, with an origin in east-central Europe, because of the mound-building distribution in the North Pontic area before the Yamna expansion, but we may never really know.

❌ Burial rite: Yamna features (with regional differences) single burials with body on its back, flexed upright knees, poor grave goods, common orientation east-west (heads to the west) inherited from Repin, in turn inherited from Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka. CWC tradition – partially connected to Złota and surrounding east-central European territories (in turn from the Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka expansion) – features single graves, body in fetal position, strict gender differentiation – men on the right, women on the left -, looking to the south, graves with standardized assemblages (objects representing affirmation of battle, hunting, and feasting). The burial rites clearly represent different ideologies.

❌ Corded decoration: Corded ware decoration appears in the Balkans during the 5th millennium, and represents a simple technique whereby a cord is twisted, or wrapped around a stick, and then pressed directly onto the fresh surface of a vessel leaving a characteristic decoration. It appears in many groups of the 5th and 4th millennium BC, but it was Globular Amphorae the culture which popularized the drinking vessels and their corded ornamentation. It appears thus in some regional groups of Yamna, but it becomes the standard pottery only in Corded Ware (especially with the A-horizon), which shows continuity with GAC pottery.

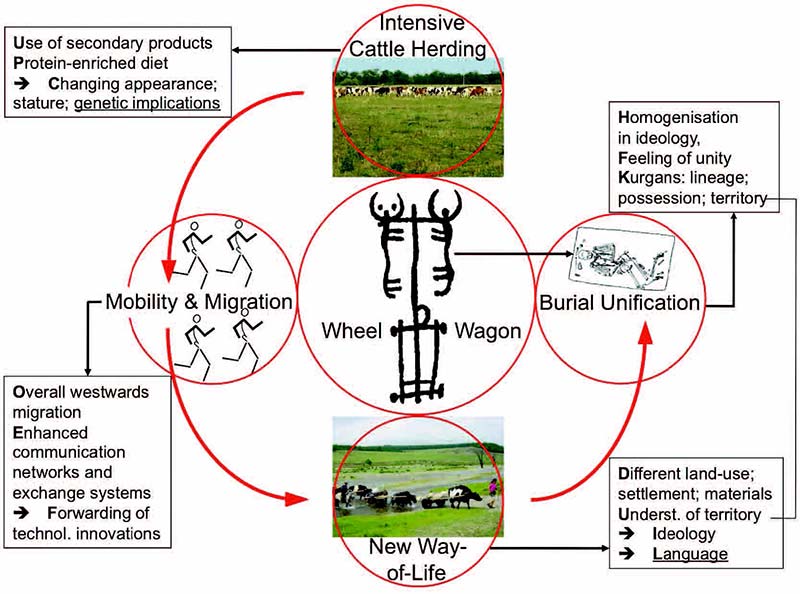

❌ Economy: Yamna expands from Repin (and Repin from Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka) as a nomadic or semi-nomadic purely pastoralist society (with occasional gathering of wild seeds), which naturally thrives in the grasslands of the Pontic-Caspian, lower Danube and Hungarian steppes. Corded Ware shows agropastoralism (as late Eneolithic forest-steppe and steppe groups of eastern Europe, such as late Trypillian, TRB, and GAC groups), inhabits territories north of the loess line, with heavy reliance of hunter-gathering depending on the specific region.

❌ Cattle herding: Interestingly, both west Yamna and Corded Ware show more reliance on cattle herding than other pastoralist groups, which – contrasted with the previous Eneolithic herding traditions of the Pontic-Caspian steppe, where sheep-goats predominate – make them look alike. However, the cattle-herding economy of Yamna is essential for its development from late Repin and its expansion through the steppes (over western territories practising more hunter-gathering and sheep-goat herding economy), and it does not reach equally the Volga-Ural region, whose groups keep some of the old subsistence economy (read more about the late Repin expansion). Corded Ware, on the other hand, inherits its economic strategy from east European groups like TRB, GAC, and especially late Trypillian communities, showing a predominance of cattle herding within an agropastoral community in the forest-steppe and forest zones of Volhynia, Podolia, and surrounding forest-steppe and forest regions.

❔ Horse riding: Horse riding and horse transport is proven in Yamna (and succeeding Bell Beaker and Sintashta), assumed for late Repin (essential for cattle herding in the seas of grasslands that are the steppes, without nearby water sources), quite likely during the Khvalynsk expansion (read more here), and potentially also for Samara, where the predominant horse symbolism of early Khvalynsk starts. Corded Ware – like the north Pontic forest-steppe and forest areas during the Eneolithic – , on the other hand, does not show a strong reliance on horse riding. The high mobility and short-term settlements characteristic of Corded Ware, that are often associated with horse riding by association with Yamna, may or may not be correct, but there is no need for horses to explain their herding economy or their mobility, and the north-eastern European areas – the one which survived after Bell Beaker expansion – did certainly not rely on horses as an essential part of their economy.

NOTE: I cannot think of more supposed similarities right now. If you have more ideas, please share in the comments and I will add them here.

Genetic similarities

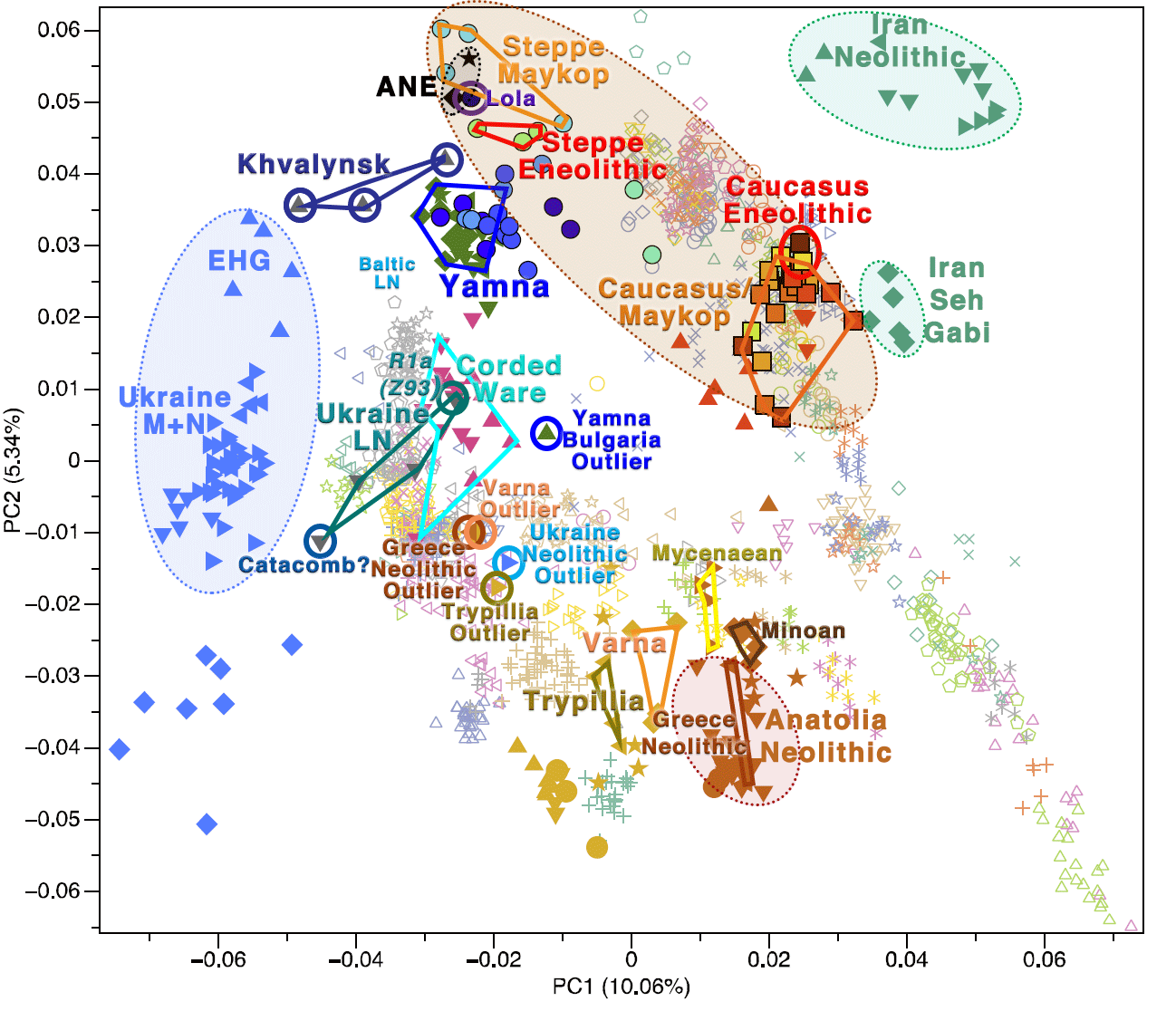

✅ EHG: This is the clearest link between both communities. We thought it was related to the expansion of ANE-related ancestry to the west into WHG territory, but now it seems that it will be rather WHG expanding into ANE territory from the Pontic-Caspian region to the east (read more on recent Caucasus Neolithic, on , and on Caucasus HG).

NOTE. Given how much each paper changes what we know about the Palaeolithic, the origin and expansion of the (always developing) known ancestral components and specific subclades (see below) is not clear at all.

❔ CHG: This is the key link between both cultures, which will delimit their interaction in terms of time and space. CHG is intermediate between EHG and Iran N (ca. 8000 BC). The ancestry is thus linked to the Caucasus south of the steppe before the emergence of North Pontic (western) and Don-Volga-Ural (eastern) communities during the Mesolithic. The real question is: when we have more samples from the steppe and the Caucasus during the Neolithic, how many CHG groups are we going to find? Will the new specific ancestral components (say CHG1, CHG2, CHG3, etc.) found in Yamna (from Khvalynsk, in the east) and Corded Ware (probably from the North Pontic forest-steppe) be the same? My guess is, most likely not, unless they are mediated by the Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka expansion (read more on CHG in the Caucasus).

❌ WHG/EEF: This is the obvious major difference – known today – in the formation of both communities in the steppe, and shows the different contacts that both groups had at least since the Eneolithic, i.e. since the expansion of Repin with its renewed Y-DNA bottleneck, and probably since before the early Khvalynsk expansion (read more on Yamna-Corded Ware differences contrasting with Yamna-Afanasevo, Yamna-Bell Beaker, and Yamna-Sintashta similarities).

NOTE 1. Some similarities between groups can be seen depending on the sampled region; e.g. Baltic groups show more similarities with southern Pontic-Caspian steppe populations, probably due to exogamy.

NOTE 2. We have this information on the differences in “steppe ancestry” between Yamna and Corded Ware, compared to previous studies, because now we have more samples of neighbouring, roughly contemporaneous Eneolithic groups, to analyse the real admixture processes. This kind of fine scale studies is what is going to show more and more differences between Khvalynsk-Yamna and Sredni Stog-Corded Ware as more data pours in. The evolution of both communities in archaeology and in PCA (see below) is probably witness to those differences yet to be published.

❌ R1: Even though some people try very hard to think in terms of “R1” vs. (Caucasus) J or G or any other upper clade, this is plainly wrong. It is possible, given what we know now, that Q1a2-M242 expanded ANE ancestry to the west ca. 13000 BC, while R1b-P279 expanded WHG ancestry to the east with the expansion of post-Swiderian cultures, creating EHG as a WHG:ANE cline. The role of R1a-M459 is unknown, but it might be related to any of these migrations, or others (plural) along northern Eurasia (read more on the expansion of R1b-P279, on Palaeolithic Q1a2, and on R1a-M417).

NOTE. I am inclined to believe in a speculative Mesolithic-Early Neolithic community involving Eurasiatic movements accross North Eurasia, and Indo-Uralic movements in its western part, with the last intense early Uralic-PIE contacts represented by the forming west (Mariupol culture) and east (Don-Volga-Ural cultures, including Samara) communities developing side by side. Before their known Eneolithic expansions, no large-scale Y-DNA bottleneck is going to be seen in the Pontic-Caspian steppe, with different (especially R1a and R1b subclades) mixed among them, as shown in North Pontic Neolithic, Samara HG, and Khvalynsk samples.

Corded Ware and ‘steppe ancestry’

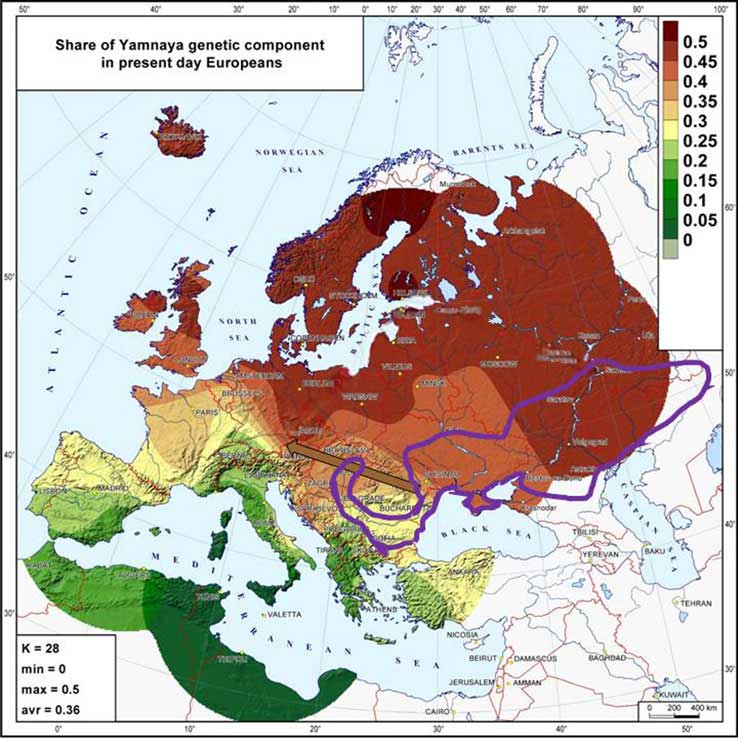

If we take a look at the evolution of Corded Ware cultures, the expansion of Bell Beakers – dominated over most previous European cultures from west to east Europe – influenced the development of the whole European Bronze Age, up to Mierzanowice and Trzciniec in the east.

The only relevant unscathed CWC-derived groups, after the expansion of Sintashta-Potapovka as the Srubna-Andronovo horizon in the Eurasian steppes, were those of the north-eastern European forest zone: between Belarus to the west, Finland to the north, the Urals to the east, and the forest-steppe region to the south. That is, precisely the region supposed to represent Uralic speakers during the Bronze Age.

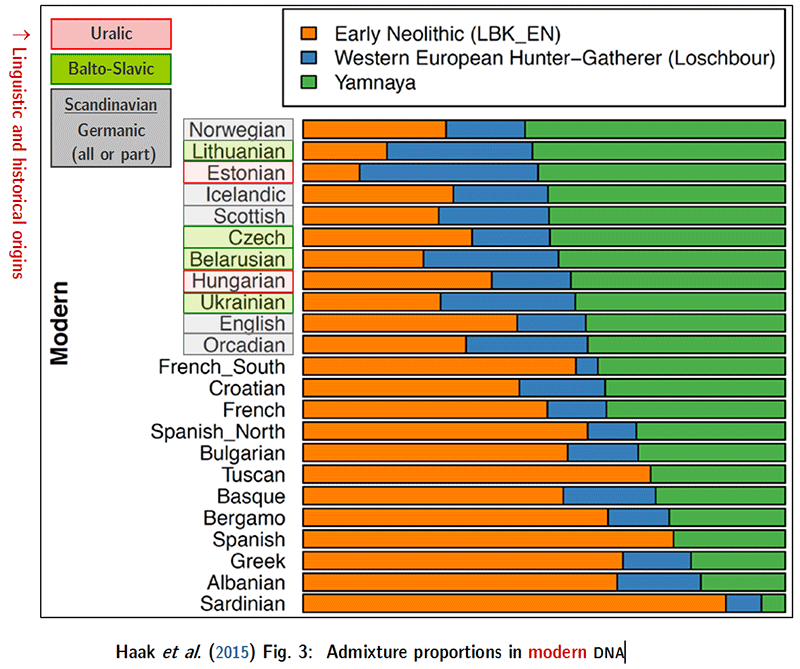

This inconsistency of steppe ancestry and its relation with Uralic (and Balto-Slavic) peoples was observed shortly after the publication of the first famous 2015 papers by Paul Heggarty, of the Max-Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (read more):

Haak et al. (2015) make much of the high Yamnaya ancestry scores for (only some!) Indo-European languages. What they do not mention is that those same results also include speakers of other languages among those with the highest of all scores for Yamnaya ancestry. Only these are languages of the Uralic family, not Indo-European at all; and their Yamnaya-ancestry signals are far higher than in many branches of Indo-European in (southern) Europe. Estonian ranks very high, while speakers of the very closely related Finnish are curiously not shown, and nor are the Saami. Hungarian is relevant less directly since this language arrived only c. 900 AD, but also high.

These data imply that Uralic-speakers too would have been part of the Yamnaya > Corded Ware movement, which was thus not exclusively Indo-European in any case. And as well as the genetics, the geography, chronology and language contact evidence also all fit with a Yamnaya > Corded Ware movement including Uralic as well as Balto-Slavic.

Both papers fail to address properly the question of the Uralic languages. And this despite — or because? — the only Uralic speakers they report rank so high among modern populations with Yamnaya ancestry. Their linguistic ancestors also have a good claim to have been involved in the Corded Ware and Yamnaya cultures, and of course the other members of the Uralic family are scattered across European Russia up to the Urals.

NOTE. Although the author was trying to support the Anatolian hypothesis – proper of glottochronological studies often published from the Max Planck Institute – , the question remains equally valid: “if Proto-Indo-European expands with Corded Ware and steppe ancestry, what is happening with Uralic peoples?”

For my part, I claimed in my draft that ancestral components were not the only relevant data to take into account, and that Y-DNA haplogroups R1a and R1b (appearing separately in CWC and Yamna-Bell Beaker-Afanasevo), together with their calculated timeframes of formation – and therefore likely expansion – did not fit with the archaeological and linguistic description of the spread of Proto-Indo-European and its dialects.

In fact, it seemed that only one haplogroup (R1b-M269) was constantly and consistenly associated with the proposed routes of Late PIE dialectal expansions – like Anthony’s second (Afanasevo) and third (Lower Danube, Balkan) waves. What genetics shows fits seamlessly with Mallory’s association of the North-West Indo-European expansion with Bell Beakers (read here how archaeologists were right).

More precise inconsistencies were observed after the publication of Olalde et al. (2017) and Mathieson et al. (2017), by Volker Heyd in Kossinna’s smile (2017). Letting aside the many details enumerated (you can read a summary in my latest draft), this interesting excerpt is from the conclusion:

NOTE. An open access ealier draft version of the paper is offered for download by the author.

Simple solutions to complex problems are never the best choice, even when favoured by politicians and the media. Kossinna also offered a simple solution to a complex prehistoric problem, and failed therein. Prehistoric archaeology has been aware of this for a century, and has responded by becoming more differentiated and nuanced, working anthropologically, scientifically and across disciplines (cf. Müller 2013; Kristiansen 2014), and rejecting monocausal explanations. The two aDNA papers in Nature, powerful and promising as they are for our future understanding, also offer rather straightforward messages, heavily pulled by culture-history and the equation of people with culture. This admittedly is due partly to the restrictions of the medium that conveys them (and despite the often relevant additional detail given as supplementary information, which is unfortunately not always given full consideration).

While I have no doubt that both papers are essentially right, they do not reflect the complexity of the past. It is here that archaeology and archaeologists contributing to aDNA studies find their role; rather than simply handing over samples and advising on chronology, and instead of letting the geneticists determine the agenda and set the messages, we should teach them about complexity in past human actions and interactions. If accepted, this could be the beginning of a marriage made in heaven, with the blessing smile of Gustaf Kossinna, and no doubt Vere Gordon Childe, were they still alive, in a reconciliation of twentieth- and twenty-first-century approaches. For us as archaeologists, it could also be the starting point for the next level of a new archaeology.

The question was made painfully clear with the publication of Olalde et al. (2018) & Mathieson et al. (2018), where the real route of Yamna expansion into Europe was now clearly set through the steppes into the Carpathian basin, later expanded as Bell Beakers.

This has been further confirmed in more recent papers, such as Narasimhan et al. (2018), Damgaard et al. (2018), or Wang et al. (2018), among others.

However, the discussion is still dominated by political agendas based on prevalent Y-DNA haplogroups in modern countries and ethnic groups.

Related

- Haplogroup R1a and CWC ancestry predominate in Fennic, Ugric, and Samoyedic groups

- The Iron Age expansion of Southern Siberian groups and ancestry with Scythians

- Evolution of Steppe, Neolithic, and Siberian ancestry in Eurasia (ISBA 8, 19th Sep)

- Mitogenomes from Avar nomadic elite show Inner Asian origin

- On the origin and spread of haplogroup R1a-Z645 from eastern Europe

- Oldest N1c1a1a-L392 samples and Siberian ancestry in Bronze Age Fennoscandia

- Consequences of Damgaard et al. 2018 (III): Proto-Finno-Ugric & Proto-Indo-Iranian in the North Caspian region

- The concept of “Outlier” in Human Ancestry (III): Late Neolithic samples from the Baltic region and origins of the Corded Ware culture

- Genetic prehistory of the Baltic Sea region and Y-DNA: Corded Ware and R1a-Z645, Bronze Age and N1c

- More evidence on the recent arrival of haplogroup N and gradual replacement of R1a lineages in North-Eastern Europe

- Another hint at the role of Corded Ware peoples in spreading Uralic languages into north-eastern Europe, found in mtDNA analysis of the Finnish population

- New Ukraine Eneolithic sample from late Sredni Stog, near homeland of the Corded Ware culture