The Indo-Iranian – Finno-Ugric connection

On the linguistic aspect, this is what the Copenhagen group had to say (in the linguistic supplement) based on Kuz’mina (2001):

(…) a northern connection is suggested by contacts between the Indo-Iranian and the Finno-Ugric languages. Speakers of the Finno-Ugric family, whose antecedent is commonly sought in the vicinity of the Ural Mountains, followed an east-to-west trajectory through the forest zone north and directly adjacent to the steppes, producing languages across to the Baltic Sea. In the languages that split off along this trajectory, loanwords from various stages in the development of the Indo-Iranian languages can be distinguished: 1) Pre-Proto-Indo-Iranian (Proto-Finno-Ugric *kekrä (cycle), *kesträ (spindle), and *-teksä (ten) are borrowed from early preforms of Sanskrit cakrá- (wheel, cycle), cattra- (spindle), and daśa- (10); Koivulehto 2001), 2) Proto-Indo-Iranian (Proto-Finno-Ugric *śata (one hundred) is borrowed from a form close to Sanskrit śatám (one hundred), 3) Pre-Proto-Indo-Aryan (Proto-Finno-Ugric *ora (awl), *reśmä (rope), and *ant- (young grass) are borrowed from preforms of Sanskrit ā́rā- (awl), raśmí- (rein), and ándhas- (grass); Koivulehto 2001: 250; Lubotsky 2001: 308), and 4) loanwords from later stages of Iranian (Koivulehto 2001; Korenchy 1972). The period of prehistoric language contact with Finno-Ugric thus covers the entire evolution of Pre-Proto-Indo-Iranian into Proto-Indo-Iranian, as well as the dissolution of the latter into Proto-Indo- Aryan and Proto-Iranian. As such, it situates the prehistoric location of the Indo-Iranian branch around the southern Urals (Kuz’mina 2001).

NOTE. While I agree with the evident ancestral nature of the *kekrä borrowing, I will repeat it here again: I don’t believe that the distinction of late Proto-Indo-Iranian from ‘Pre-Proto-Indo-Aryan’ loans is warranted; not for words reconstructed from recent Finno-Ugric languages.

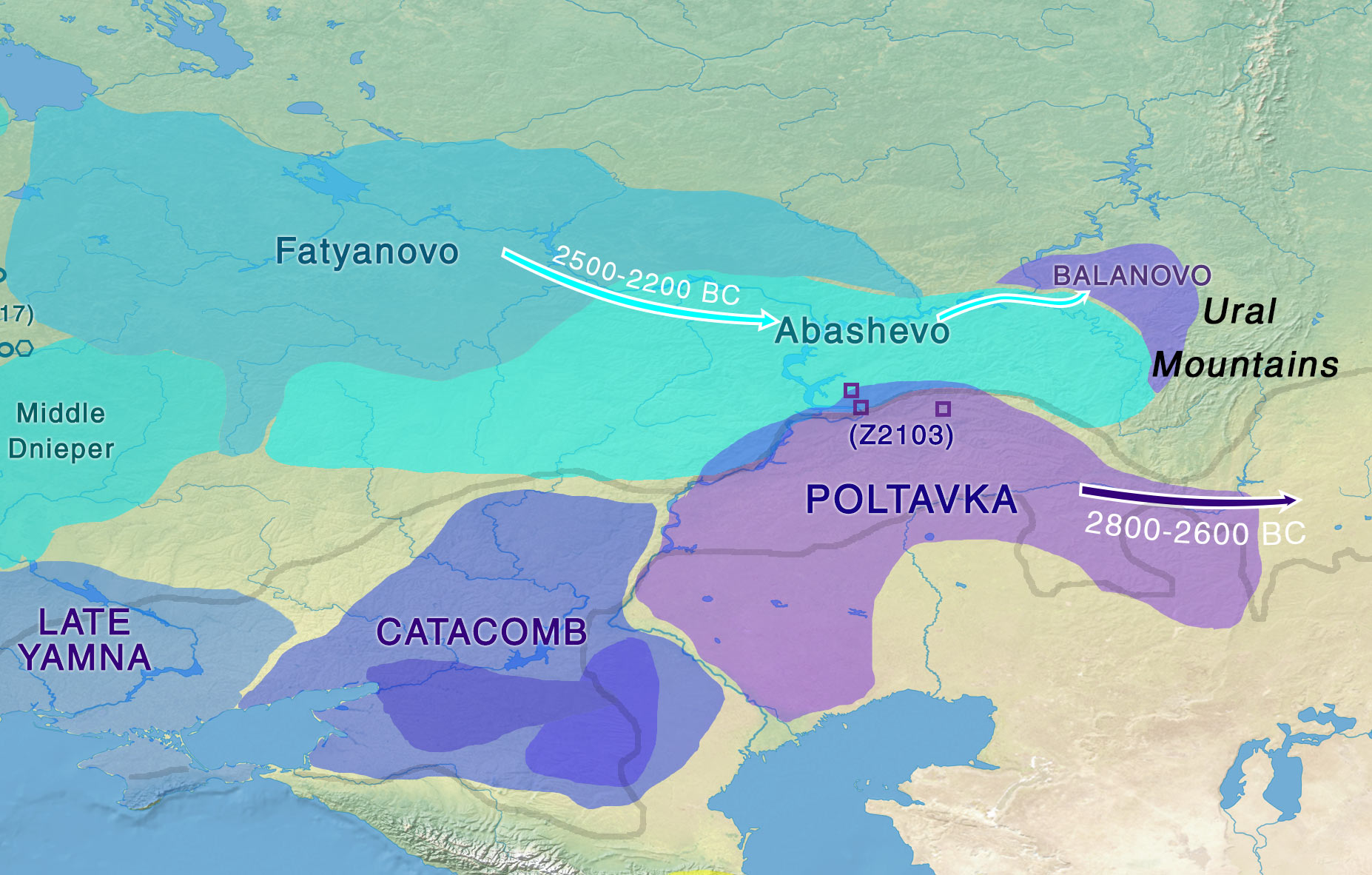

In this period of a Pre-Proto-Indo-Iranian community, which is to be associated with East Yamna/Poltavka, ca. 3000-2400 BC – as accepted in the supplement from de Barros Damgaard et al. (Nature 2018) – , both Poltavka and Abashevo/Balanovo herders were expanding ca. 2800-2600 BC to the east (and Abashevo already admixing into Poltavka territory), near the southern Urals.

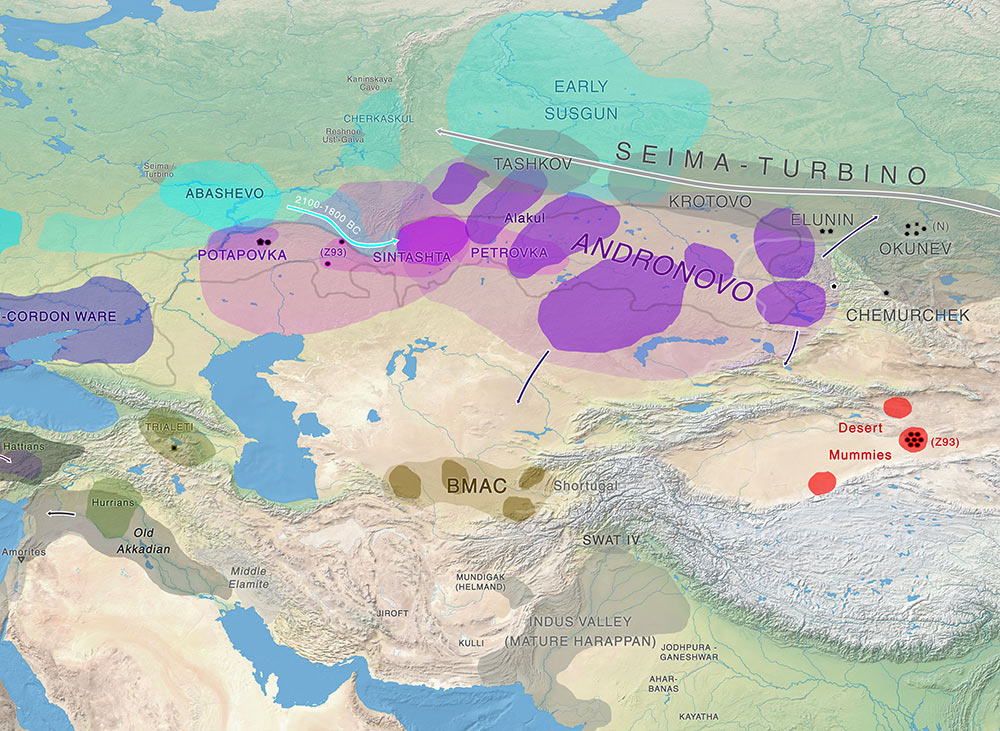

There is no other, clearer, later connection between Finno-Ugric and Proto-Indo-Iranian speakers. Even the arrival of the Seima-Turbino phenomenon (after ca. 2000 BC), if it brought migrants to North-East Europe, would not fit the linguistic, archaeological, or genetic data. It is by now quite clear that Seima-Turbino does not fit with incoming N1c1 lineages and/or Siberian ancestry, either, for those looking for these as potential signs of incoming Uralic speakers.

While the Copenhagen group did not have access to data from Sintashta ca. 2100 BC onwards – now available in Narasimhan et al. (2018) – when submitting the papers, we already know that there was a clear long period of slow progressive admixture in the North Caspian region. It can be seen in the genetic contribution of Yamna to incoming Abashevo groups, and in the R1b-L23 samples still appearing in Sintashta until ca. 1800 BC (as I predicted could happen).

Since the first sample signalling incoming Abashevo migrants is found in the Poltavka outlier dated ca. 2700 BC (of R1a-Z93 lineage), this represents a rather unique, several centuries long process of admixture in the North Caspian region, different from the massive Afanasevo or Bell Beaker migrations in Asia and Europe, whereby a great part of the native male population was suddenly replaced.

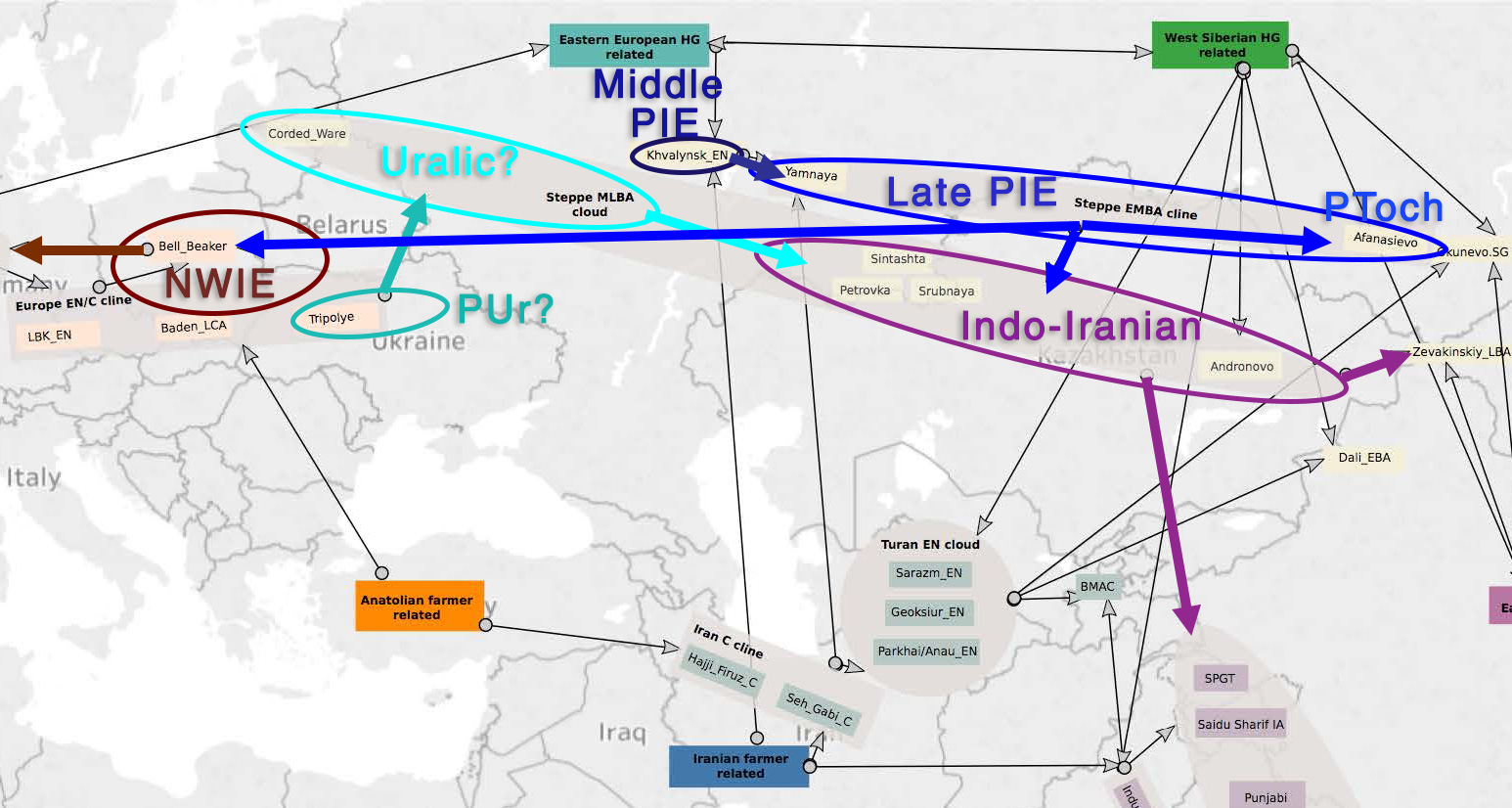

This offers further support for language continuity despite genetic replacement in the development of East Yamna/Poltavka (part of the Steppe EMBA cline, formed by Yamna and Afanasevo) mixing with Abashevo migrants (probably identical to Corded Ware samples) to form Potapovka, Sintashta, and later Srubna, and Andronovo communities (all forming, with Corded Ware groups, a wide Eurasian Steppe MLBA cloud). See the available data from Narasimhan et al. (2018).

The continuous interactions and migrations left thus eventually two communities in the southern Urals genetically similar, but ethnolinguistically diverse:

- To the north, Abashevo-Balanovo – but potentially also Fatyanovo, and related North-East European late Corded Ware groups – borrowed necessary words from Indo-Iranian neighbours, while maintaining their Finno-Ugric language and culture.

- To the south, immigrants (or their descendants) of Abashevo origin expanding among Pre-Proto-Indo-Iranian-speaking North Caspian communities assimilated the surrounding culture and language, giving it their own accent (i.e. ‘satemizing’ it) and turning it into Proto-Indo-Iranian (see e.g. Parpola’s account).

Anthropologically, this ‘long-term founder effect’ that appears as genetic replacement is probably explained by the faster life history in MLBA North Caspian populations, likely due to a combination of changing environmental and social circumstances.

NOTE. The prevalent explanation before the latest studies on the Sintashta society were social strife and isolation of small groups, an argument I used in my demic diffusion model. Other, similar cases of proven linguistic continuity despite genetic replacement are seen in Iberian Bronze Age after the expansion of R1b-L23 lineages (with Vasconic, Iberian, and Tartessian surviving at least until proto-historic times), and in Remote Oceania.

Implications for Late PIE migrations

I am happy to see that people are resorting now to dialectal classifications and Y-DNA to explain the findings in Old Hittites, Tocharians (and related migrations), and Indo-Iranians. It is especially interesting to see precisely this Danish group downplay the relevance of ancestry and favor complex anthropological models when assessing migrations and ethnolinguistic identification.

So let’s talk about the growing elephant in the room.

It seems we all accept now Tocharian’s more archaic Late PIE nature, which is supported by waves of late Khvalynsk migrants starting probably ca. 3300 BC, as seen in different samples to the east in Central Asia, and to the south in Iran. Almost all of them share R1b-L23 lineages.

NOTE. Whereas their early LPIE dialects have not survived to historic times, the rather speculative hypotheses of Euphratic and Gutian languages may be of interest.

We also know of the coetaneous migrants that settled to the west of the Don River (in the territory of the previous late Sredni Stog culture), to form the western South-Bug / Lower Don groups, which, together with the Volga-Ural / North Caucasian groups formed the early Yamna culture, that dominated from ca. 3300 BC over the Pontic-Caspian steppe.

It is only logical that the other attested languages belonging to the common Late PIE trunk must come from these groups, which must have stuck together for quite some time – after the recently proven late Khvalynsk migrations – , to allow for the spread of isoglosses (not found in Tocharian) among them.

This is agreed, even by the Copenhagen group, who expressly state that Yamna is to be identified with the rest of Late PIE languages after the Tocharian-related migrations.

The period of an early Yamna community constrained to the Pontic-Caspian steppe (ca. 3300-3000 BC) is followed by renewed waves of Late Proto-Indo-European migrations, during which areal contacts and innovations (even between unrelated LPIE branches) can still be reconstructed.

These later migrations can be precisely described as follows (after the latest studies):

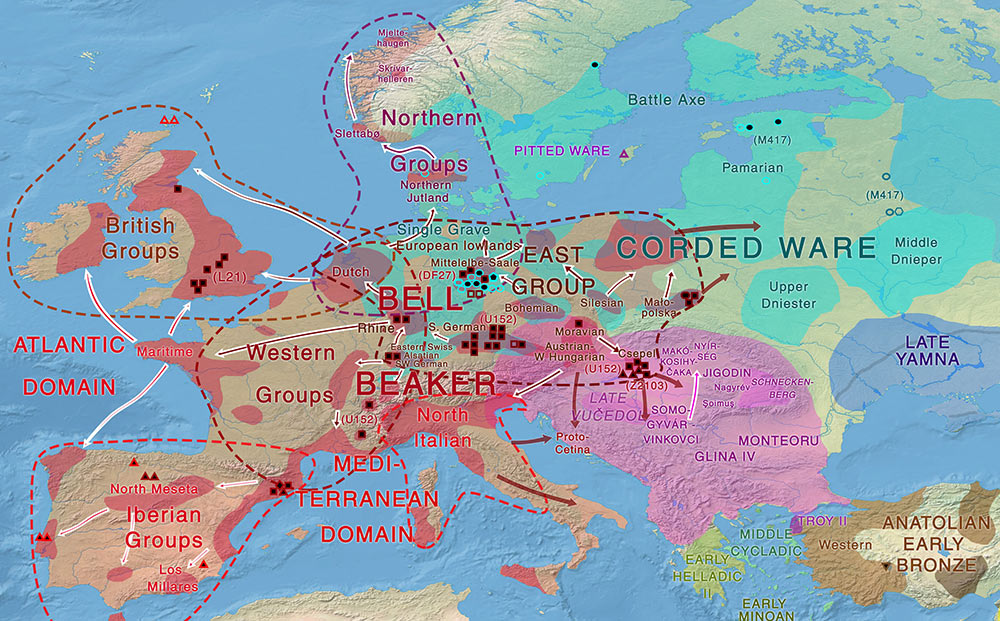

- Yamna migrants, of mixed R1b-L51 and R1b-Z2103 lineages, settle ca. 3000-2600 BC along the lower Danube, in the Balkans and the Carpathian basin, giving rise later to groups of:

- East Bell Beakers expanding ca. 2500 BC onwards from the Carpathian basin into the upper Danube and all of Europe, mainly with R1b-L51 subclades (see Olalde et al. 2018);

- Palaeo-Balkan migrants, expanding mainly with R1b-Z2103 subclades, representing languages ancestral to Proto-Greek and other Balkan languages.

- In the Pontic-Caspian steppe, early Yamna groups evolve into (from west to east) Late Yamna, Catacomb, and Poltavka groups, ca. 2800-2300 BC, all still dominated by R1b-L23 lineages (see discussion on the Catacomb sample), with:

- Poltavka peoples admixing with Abashevo migrants to form admixed Potapovka and Sintashta-Petrovka groups, showing still after ca. 1800 BC a mixed society of R1a-Z93 and R1b-Z2103 lineages (see Narasimhan et al. 2018);

- Expanding early Proto-Iranian and Proto-Indo-Aryan groups in Srubna (to the west) and Andronovo (to the east), during the first half of the 2nd millennium BC, dominate over the Bronze Age steppe and Central Asia with expanding R1a-Z93 lineages.

Conclusion

1) East Bell Beakers clearly dominated culturally and genetically over almost all of Europe, ca. 2500-2000 BC, including previous Corded Ware territory, representing thus the most recent massive migration of steppe peoples in Europe, and being the only pan-European culture derived from Late Proto-Indo-European-speaking Yamna. They must therefore be identified with North-West Indo-European speakers, as proposed by Mallory (2013), and not just Italo-Celtic (as supported recently by the Danish school, based on Gimbutas’ outdated model):

1.A) For Germanic, we already have proof that an appropriate, unitary Scandinavian society, ripe for the development of a common Pre-Germanic language (that expanded much later, during the Iron Age, as Proto-Germanic) could have developed only after the arrival of Bell Beakers (see Prescott 2017). The association of proto-historic Germanic tribes mainly with the expansion of R1b-U106 lineages bears witness to that.

NOTE. Even without taking into account the likely L51 samples from Khvalynsk, it is by now quite clear that R1b-L51 lineages were already admixed in Yamna settlers from the Carpathian Basin, and any subclade of U106, L21, DF27, or U152 can thus be found everywhere in Europe associated with any of those North-West Indo-European migrations. What we are seing later, as in the East Bell Beaker migrants arriving in the British Isles (L21), Iberia (DF27), or the Netherlands/Scandinavia (U106), is the further reduction in variability coupled with the expansion of a few sucessful families (and their lineages), as we know it usually happens during migrations.

1.B) For Balto-Slavic, it seems they were not part of the eastern Corded Ware peoples: the Copenhagen group denies an Indo-Slavonic group in the Nature paper, referring instead to a dominion of early Iranians in the steppes, following their traces to proto-historic and historic Iranian-speaking peoples. And we knew already that Bell Beakers dominated over Central-East Europe, before the resurge of R1a-Z645 lineages in the region, which is compatible with the North-West Indo-European nature of their language undergoing a satemization process similar (but not equal to) to the Indo-Iranian one (see the full discussion on Balto-Slavic here).

NOTE. The few ancestral traits common to Germanic and Balto-Slavic are today considered a common substrate language to both, and not due to close contacts (and still less a common branch, as was proposed in the 1st half of the 20th c.). You can read e.g. Kortlandt’s Baltic, Slavic, Germanic (2017), or our Corded Ware substrate hypothesis (2017). In both theories, the referenced substrate is likely a non-Indo-European language, and in both cases it is related to the Corded Ware culture, which represents their most common immediate ancestral population before the spread of Bell Beakers.

2) The late Corded Ware groups of Finland and Estonia, as well as Fatyanovo and Abashevo (and succeeding groups of Eastern Europe) may now be more clearly associated with Proto-Finno-Ugric dialects, and thus probably Corded Ware groups in general with Uralic languages, whose western branches have not survived to this day, with their culture and language being replaced quite early by expanding Bell Beakers.

NOTE. While the demise of Central and Central-East European CWC groups is evident, continuous contacts among Battle Axe culture groups in Scandinavia and the Gulf of Finland through the Baltic Sea – and the strong Bronze Age Palaeo-Germanic influence on Finnic languages (stronger than earlier Indo-Iranian borrowings) may point to the continuity of Proto-Finnic in Northern Scandinavia, which may force a reinterpretation of the prehistoric location of Proto-Finnic-speaking groups.

Those supporting a Corded Ware expansion of Germanic or Balto-Slavic with R1a subclades, now rejecting the expansion of Proto-Indo-European from an Anatolian homeland (following the spread of Neolithic farmer ancestry), and negating the close Proto-Indo-Iranian – Uralic contacts, are willfully ignoring linguistic, archaeological, and genetic data whenever it does not fit with their previous theories.

Good times ahead to chase false syllogisms and contradictions everywhere.

Related:

- Eurasian steppe dominated by Iranian peoples, Indo-Iranian expanded from East Yamna

- No large-scale steppe migration into Anatolia; early Yamna migrations and MLBA brought LPIE dialects in Asia

- Early Indo-Iranian formed mainly by R1b-Z2103 and R1a-Z93, Corded Ware out of Late PIE-speaking migrations

- Y-DNA haplogroup R1b-Z2103 in Proto-Indo-Iranians?

- The Aryan migration debate, the Out of India models, and the modern “indigenous Indo-Aryan” sectarianism

- Consequences of O&M 2018 (III): The Balto-Slavic conundrum in Linguistics, Archaeology, and Genetics

- North Pontic steppe Eneolithic cultures, and an alternative Indo-Slavonic model

- Olalde et al. and Mathieson et al. (Nature 2018): R1b-L23 dominates Bell Beaker and Yamna, R1a-M417 resurges in East-Central Europe during the Bronze Age

- The concept of “Outlier” in Human Ancestry (III): Late Neolithic samples from the Baltic region and origins of the Corded Ware culture

- New Ukraine Eneolithic sample from late Sredni Stog, near homeland of the Corded Ware culture

- The renewed ‘Kurgan model’ of Kristian Kristiansen and the Danish school: “The Indo-European Corded Ware Theory”

- Correlation does not mean causation: the damage of the ‘Yamnaya ancestral component’, and the ‘Future America’ hypothesis

- Germanic–Balto-Slavic and Satem (‘Indo-Slavonic’) dialect revisionism by amateur geneticists, or why R1a lineages *must* have spoken Proto-Indo-European