Open Access The genetic prehistory of the Baltic Sea region, by Mittnik et al., Nature Communications 9: 442 (2018), based on preprint The Genetic History of Northern Europe, at BioRxirv.

As you can see, it follows my predictions in terms of haplogroups, and sadly the same trend to substitute ‘Yamna’ for ‘steppe’ while keeping linguistic interpretations unchanged…

Important excerpts for the Indo-European question (emphasis mine):

Mesolithic to Neolithic

In the archaeological understanding, the transition from Mesolithic to Neolithic in the Eastern Baltic region does not coincide with a large-scale population turnover and a stark shift in economy as seen in Central and Southern Europe. Rather, it is signified by a change in networks of contacts and the use of pottery, among other material, cultural and economic changes. Our results suggest continued admixture between groups in the south of the Eastern Baltic region, who are more closely related to WHG, and northern or eastern groups, more closely related to EHG. Neolithic social networks from the Eastern Baltic to the River Volga could also explain similarities of the hunter-gatherer pottery styles, although morphologically analogous ceramics might also have developed independently due to similar functionality. The genetic evidence for a change in networks and possibly even a large-scale population movement is most pronounced in the Middle Neolithic in individuals attributed to the CCC. The distribution of this culture overlaps in the north with the Narva culture and extends further north to Finland and Karelia. Its spread in the Eastern Baltic is linked with a significant change in imported raw materials, artefacts, and the appearance of village-like settlements15.

Neolithic to Chalcolithic

We see a further population movement into the regions surrounding the Baltic Sea with the CWC in the Late Neolithic that was accompanied by the first evidence of extensive animal husbandry in the Eastern Baltic. The presence of ancestry from the Pontic-Caspian Steppe among Baltic CWC individuals without the genetic component from north-western Anatolian Neolithic farmers must be due to a direct migration of steppe pastoralists that did not pick up this ancestry in Central Europe. It suggests import of the new economy by an incoming steppe-like population independent of the agricultural societies that were already established to the south and west of the Baltic Sea. The presence of direct contacts to the steppe could lend support to a linguistic model that sees an early branching of Balto-Slavic from a Proto-Indo-European language, for which the west Eurasian steppe was proposed as a homeland. However, as farmer ancestry is found in later Eastern Baltic individuals, it is likely that considerable individual mobility and a network of contact throughout the range of the CWC facilitated its spread eastward, possibly through exogamous marriage practices. Conversely, the appearance of mitochondrial haplogroup U4 in the Central European Late Neolithic after millennia of absence could indicate female gene-flow from the Eastern Baltic, where this haplogroup was present at high frequency.

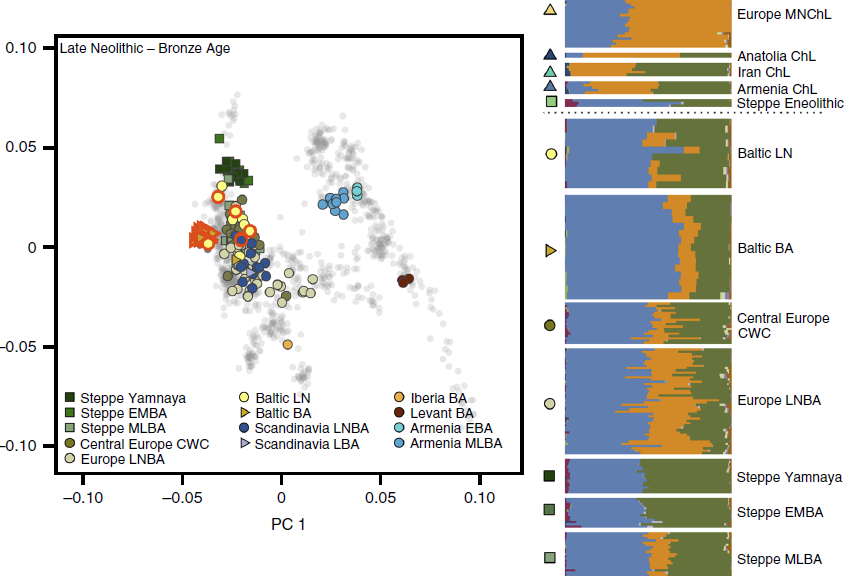

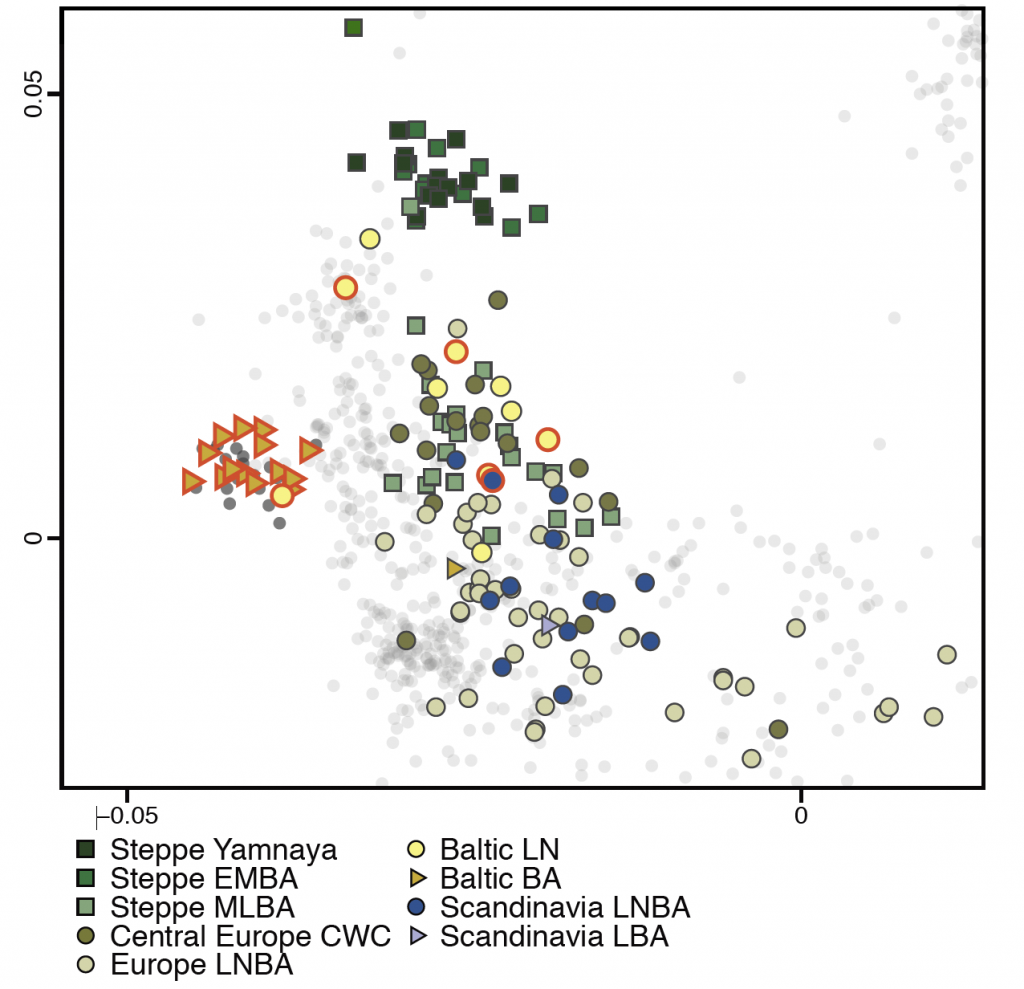

So, we see that no farmer ancestry is found in the Baltic (unlike in Western Yamna), that PCA of Late Neolithic is closer to Corded Ware samples from Europe (or to earlier samples from the region) and not to Yamna, as suggested at first by the Zvejnieki individual.

There obviously was exogamy – which may in fact justify the findings in PCA close to Yamna (like the Zvejnieki sample), although researchers obviate that.

Also, as expected, no R1b-M269 in the Baltic (during the Corded Ware period), most are R1a with the majority showing subclade R1a-Z645 (and others poor SNP coverage), which support the reduction in haplogroup diversity to this very subclade during the expansion of Corded Ware peoples, as I predicted it would happen.

Bronze Age

Local foraging societies were, however, not completely replaced and contributed a substantial proportion to the ancestry of Eastern Baltic individuals of the latest LN and Bronze Age. This ‘resurgence’ of hunter-gatherer ancestry in the local population through admixture between foraging and farming groups recalls the same phenomenon observed in the European Middle Neolithic and is responsible for the unique genetic signature of modern-day Eastern Baltic populations.

We suggest that the Siberian and East Asian related ancestry in Estonia, and Y-haplogroup N in north-eastern Europe, where it is widespread today, arrived there after the Bronze Age, ca. 500 calBCE, as we detect neither in our Bronze Age samples from Lithuania and Latvia. As Uralic speaking populations of the Volga-Ural region show high frequencies of haplogroup N, a connection was proposed with the spread of Uralic language speakers from the east that contributed to the male gene pool of Eastern Baltic populations and left linguistic descendants in the Finno-Ugric languages Finnish and Estonian. A potential future direction of research is the identification of the proximate population that contributed to the arrival of this eastern ancestry into Northern Europe.

I predicted that haplogroup N arrived probably to the region west of the Urals with the Sejma-Turbino phenomenon, and that it expanded quite late, probably through founder effects. A late arrival to the region leaves obviously (safe for these researchers and others working with old ideas) only the Corded Ware culture (represented by steppe admixture and mainly haplogroup R1a-Z645) as the vector of expansion of Uralic languages, which show obviously a dialectalization process and regional expansion much older than 500 BC…

It is funny to see how people keep trying to identify R1a with ‘Yamnaya’, now ‘steppe’, but always Indo-European (an ethnolinguistic term, mind you) supposedly because of the ‘Yamnaya’ (now ‘steppe’) admixture, but the only ‘mark’ of Uralic languages for the same researchers in the same paper using this very concept is nevertheless, paradoxically, haplogroup N, with an assumption explicitly based on prevalence in modern populations…

This admixture vs. haplogroup question for language and culture identification in genetic papers is really gettting messed up with new data, now in a contortionist-like way…

Images and text: Content of the paper is licensed under CC-by 4.0.

See also:

- The Indo-European demic diffusion model, and the “R1b – Indo-European” association

- Massive Migrations? The Impact of Recent aDNA Studies on our View of Third Millennium Europe

- More evidence on the recent arrival of haplogroup N and gradual replacement of R1a lineages in North-Eastern Europe

- The new “Indo-European Corded Ware Theory” of David Anthony

- Bell Beaker/early Late Neolithic (NOT Corded Ware/Battle Axe) identified as forming the Pre-Germanic community in Scandinavia

- The renewed ‘Kurgan model’ of Kristian Kristiansen and the Danish school: “The Indo-European Corded Ware Theory”

- Correlation does not mean causation: the damage of the ‘Yamnaya ancestral component’, and the ‘Future America’ hypothesis

- Something is very wrong with models based on the so-called ‘Yamnaya admixture’ – and archaeologists are catching up (II)

- New Ukraine Eneolithic sample from late Sredni Stog, near homeland of the Corded Ware culture

- Germanic–Balto-Slavic and Satem (‘Indo-Slavonic’) dialect revisionism by amateur geneticists, or why R1a lineages *must* have spoken Proto-Indo-European