It has been known for a long time that the Caucasus must have hosted many (at least partially) isolated populations, probably helped by geographical boundaries, setting it apart from open Eurasian areas.

David Reich writes in his book the following about India:

The genetic data told a clear story. Around a third of Indian groups experienced population bottlenecks as strong or stronger than the ones that occurred among Finns or Ashkenazi Jews. We later confirmed this finding in an even larger dataset that we collected working with Thangaraj: genetic data from more than 250 jati groups spread throughout India (…)

Rather than an invention of colonialism as Dirks suggested, long-term endogamy as embodied in India today in the institution of caste has been overwhelmingly important for millennia. (…)

The Han Chinese are truly a large population. They have been mixing freely for thousands of years. In contrast, there are few if any Indian groups that are demographically very large, and the degree of genetic differentiation among Indian jati groups living side by side in the same village is typically two to three times higher than the genetic differentiation between northern and southern Europeans. The truth is that India is composed of a large number of small populations.

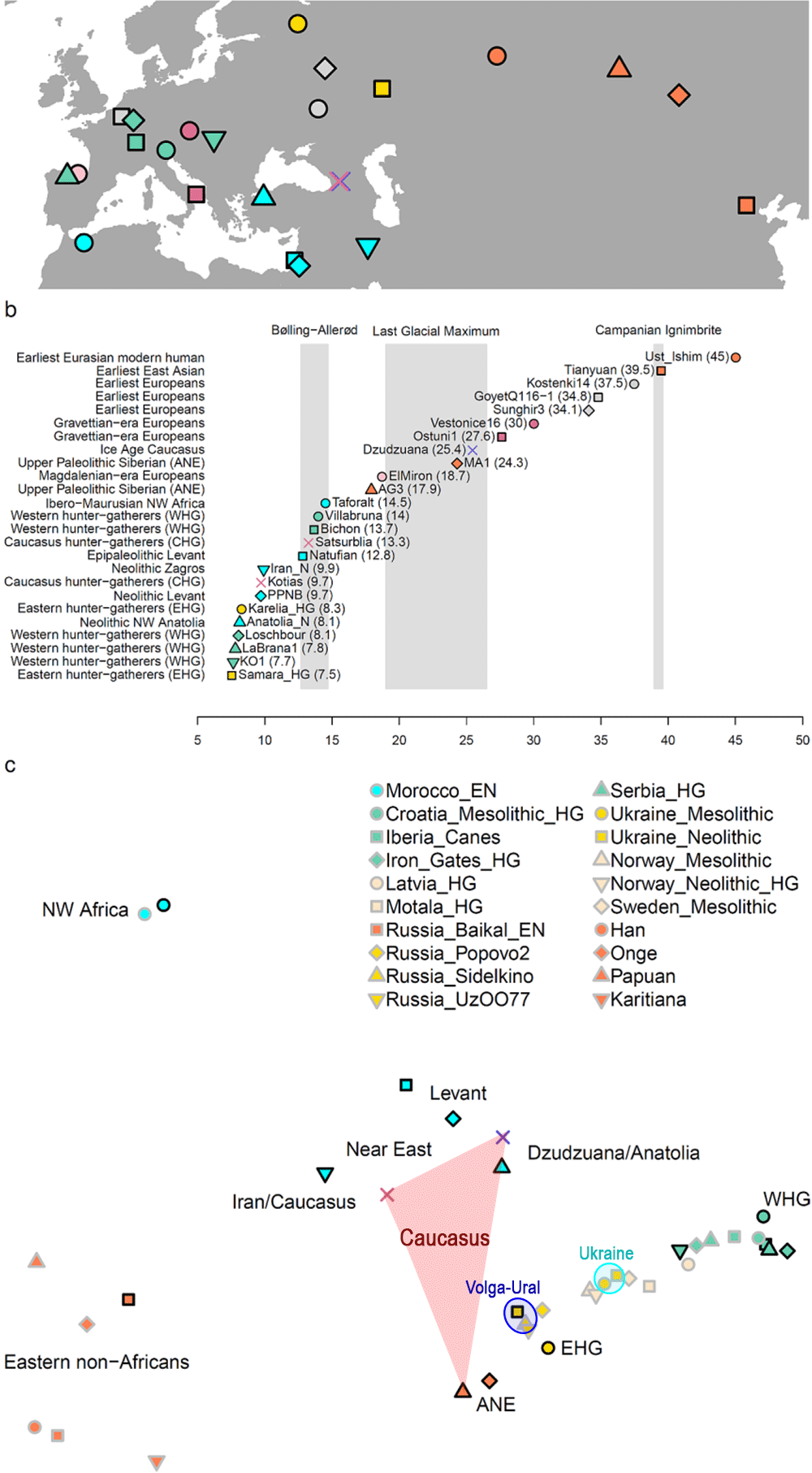

There is little doubt now, based on findings spanning thousands of years, that the Mesolithic and Neolithic Caucasus hosted various very small populations, even if the ancestral components may be reduced to the few known to date (such as ANE, EHG, AME*, ENA, CHG, and other “deep” ancestral components).

NOTE. I will call the ancestral component of Dzudzuana/Anatolian hunter-gatherers Ancient Middle Easterner (AME), to give a clear idea of its likely extension during the Late Upper Palaeolithic, and to avoid using the more simplistic Dzudzuana, unless it is useful to mention these specific local samples.

Genetic labs have a strong fixation with ancestry. I guess the use of complex statistical methods gives professionals and laymen alike the feeling of dealing with “Science”, as opposed to academic fields where you have to interpret data. I think language reveals a lot about the way people think, and the fact that ancestral components are called ‘lineages’ – while not wrong per se – is a clear symptom of the lack of interest in the true lineages: Y-DNA haplogroups.

Y-DNA bottlenecks

It has become quite clear that male-biased migrations are often the ones which can be confidently followed for actual population movements and ethnolinguistic identification, at least until the Iron Age. The frequently used Palaeolithic clusters offer a clear example of why ancestry does not represent what some people believe: They merely give a basic idea of sizeable population replacements by distant peoples.

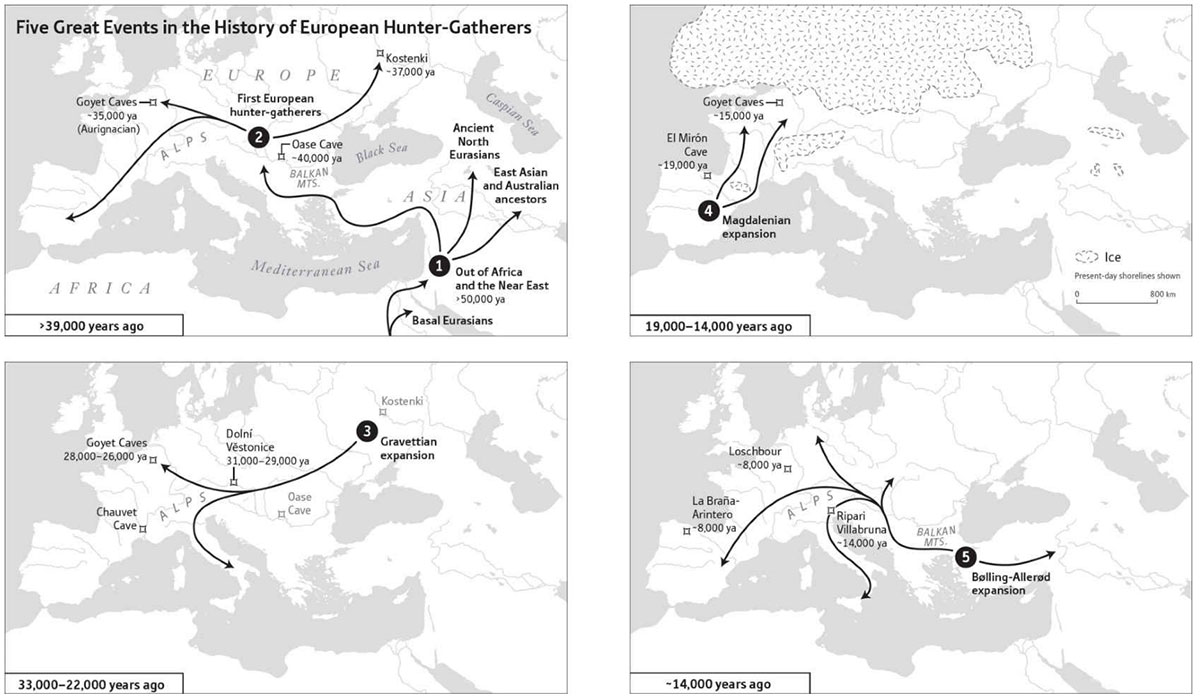

Both concepts are important: sizeable and distant peoples. For example, during the Upper Palaeolithic in Europe there was a sizeable population replacement of the Aurignacian Goyet cluster by the Gravettian Vestonice cluster (probably from populations of far eastern Russia) coupled with the arrival of haplogroup I, although during the thousands of years that this material culture lasted, the previously expanded C1a2 lineages did not disappear, and there were probably different resurgence and admixture events.

Haplogroup I certainly expanded with the Gravettian culture to Iberia, where the Goyet ancestry did not change much – probably because of male-driven migrations -, to the extent that during the Magdalenian expansions haplogroup I expanded with an ancestry closer to Goyet, in what is called a ‘resurge’ of the Goyet cluster – even though there is a clear replacement of male lines.

The Villabruna (WHG) cluster is another good example. It probably spread with haplogroup R1b-L754, which – based on the extra ‘East Asian’ affinity of some samples and on modern samples from the Middle East – came probably from the east through a southern route, and not too long before the expansion of WHG likely from around the Black Sea, although this is still unclear. The finding of haplogroup I in samples of mostly WHG ancestry could confuse people that do not care about timing, sub-structured populations, and gene flow.

NOTE. If you don’t understand why ‘clusters’ that span thousands of years don’t really matter for the many Palaeolithic population expansions that certainly happened among hunter-gatherers in Europe, just take a look at what happened with Bell Beakers expanding from Yamna into western Europe within 500 years.

If we don’t thread carefully when talking about population migrations, these terms are bound to confuse people. Just as the fixation on “steppe ancestry” – which marks the arrival in Chalcolithic Europe of peoples from the Pontic-Caspian region – has confused a lot of researchers to this day.

When I began to write about the Indo-European demic diffusion model, my concern was to find a single spot where a North-West Indo-European proto-language could have expanded from ca. 2000 BC (our most common guesstimate). Based on the 2015 papers, and in spite of their conclusions, I thought it had become clear that Corded Ware was not it, and it was rather Bell Beakers. I assumed that Uralic was spoken to the north (as was the traditional belief), and thus Corded Ware expanded from the forest zone, hence steppe ancestry would also be found there with other R1a lineages.

With the publication of Mathieson et al. (2017) and Olalde et al. (2017), I changed my mind, seeing how “steppe ancestry” did in fact appear quite late, hence it was likely to be the result of very specific population movements, probably directly from the Caucasus. Later, Mathieson published in a revision the sample from Alexandria of hg R1a-M417 (probably R1a-Z645, possibly Z93+), which further supported the idea that the migration of Corded Ware peoples started near the North Pontic forest-steppe (as I included in a the next revision).

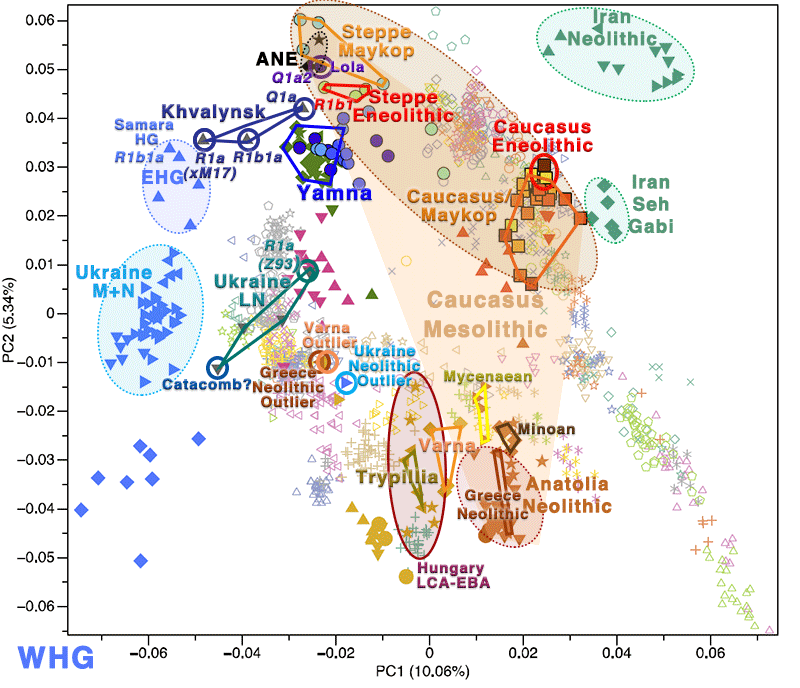

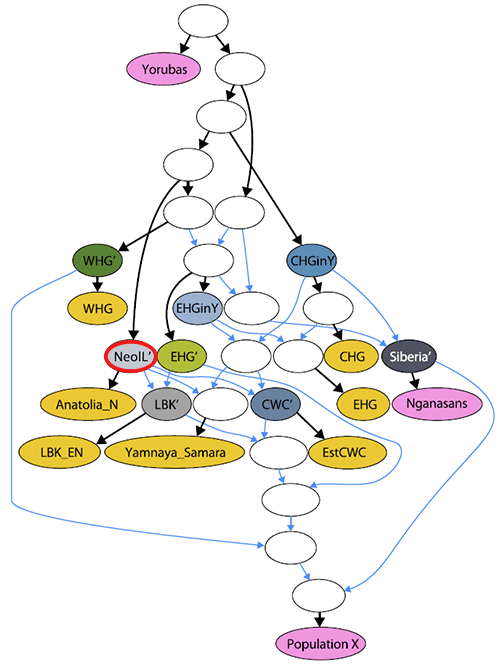

The question remains the same I repeated recently, though: where do the extra Caucasus components (i.e. beyond EHG) of Eneolithic Ukraine/Corded Ware and Khvalynsk/Yamna come from?

Steppe ancestry: “EHG” + “CHG”?

About EHG ancestry

From Lazaridis et al. (2018):

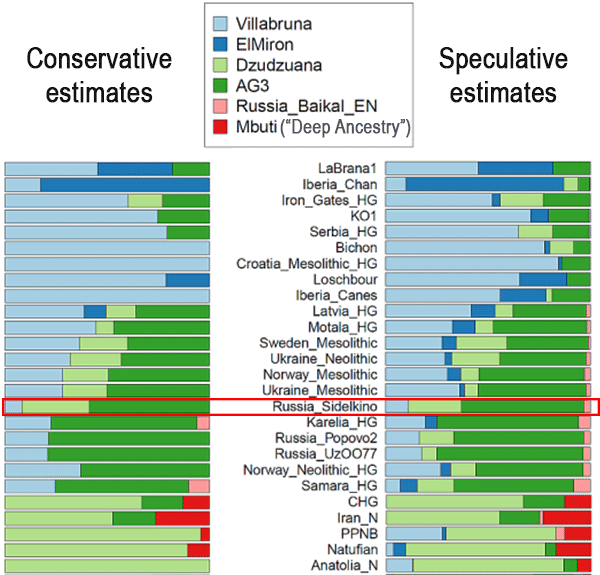

Considering 2-way mixtures, we can model Karelia_HG as deriving 34 ± 2.8% of its ancestry from a Villabruna-related source, with the remainder mainly from ANE represented by the AfontovaGora3 (AG3) sample from Lake Baikal ~17kya.

AG3 was likely of haplogroup Q1a (as reported by YFull, see Genetiker), and probably the ANE ancestry found in Eastern Europe accompanied a Palaeolithic migration of Q1a2-M25 (formed ca. 22600 BC, TMRCA ca. 14300 BC).

NOTE. You can read more about the expansion of Q lineages during the Palaeolithic.

Combined with what we know about the Eneolithic Steppe and Caucasus populations – it is likely that ANE ancestry remained the most important component of some of the small ghost populations of the Caucasus until their emergence with the Lola culture.

The first sample we have now attributed to the EHG cluster is Sidelkino, from the Samara region (ca. 9300 BC), mtDNA U5a2. In Damgaard et al. (Science 2018), Yamnaya could be modelled as a CHG population related to Kotias Klde (54%) and the remaining from ANE population related to Sidelkino (>46%), with the following split events:

- A split event, where the CHG component of Yamnaya splits from KK1. The model inferred this time at 27 kya (though we note the larger models in Sections S2.12.4 and S2.12.5 inferred a more recent split time).

- A split event, where the ANE component of Yamnaya splits from Sidelkino. This was inferred at about about 11 kya.

- A split event, where the ANE component of Yamnaya splits from Botai. We inferred this to occur 17 kya. Note that this is above the Sidelkino split time, so our model infers Yamnaya to be more closely related to the EHG Sidelkino, as expected.

- An ancestral split event between the CHG and ANE ancestral populations. This was inferred to occur around 40 kya.

Other samples classified as of the EHG cluster:

- Popovo2 (ca. 6250 BC) of hg J1, mtDNA U4d – Po2 and Po4 from the same site (ca. 6550 BC) show continuity of mtDNA.

- Karelia_HG, from Juzhnii Oleni Ostrov (ca. 6300 BC): I0211/UzOO40 (ca. 6300 BC) of hg J1(xJ1a), mtDNA U4a; and I0061/UzOO74 of hg R1a1(xR1a1a), mtDNA C1

- UzOO77 and UzOO76 from Juzhnii Oleni Ostrov (ca. 5250 BC) of mtDNA R1b.

- Samara_HG from Lebyanzhinka (ca. 5600 BC) of hg R1b1a, mtDNA U5a1d.

From the analysis of Lazaridis et al. (2018), we have some details about their admixture:

About Anatolia_Neolithic ancestry

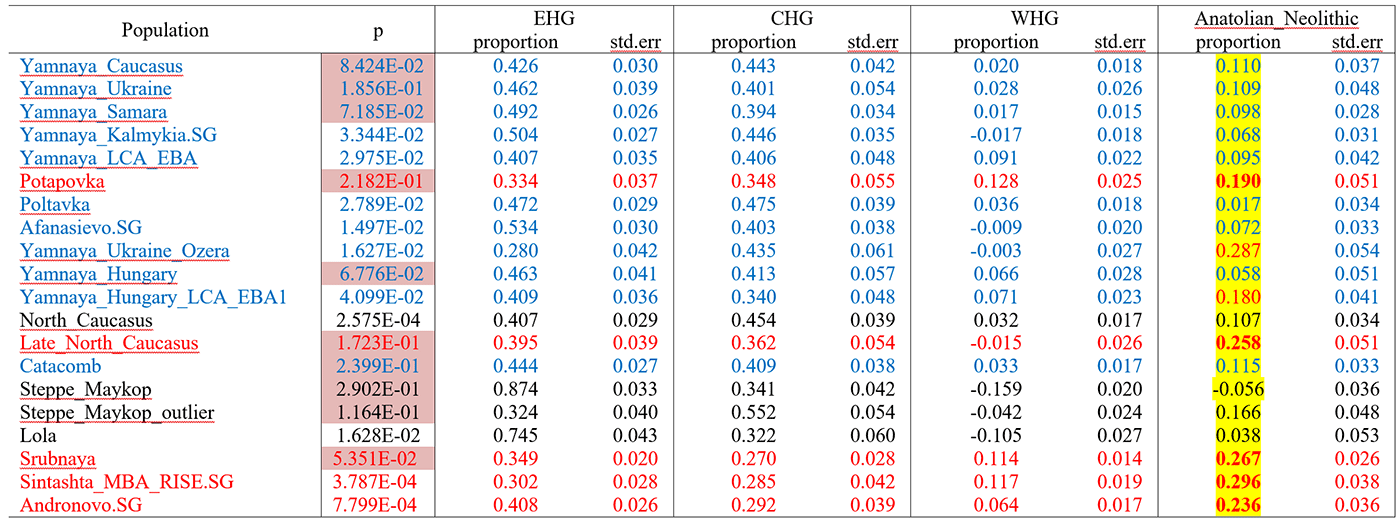

About the enigmatic Anatolia_Neolithic-related ancestry found in Pontic-Caspian steppe samples, this is what Wang et al. (2018) had to say:

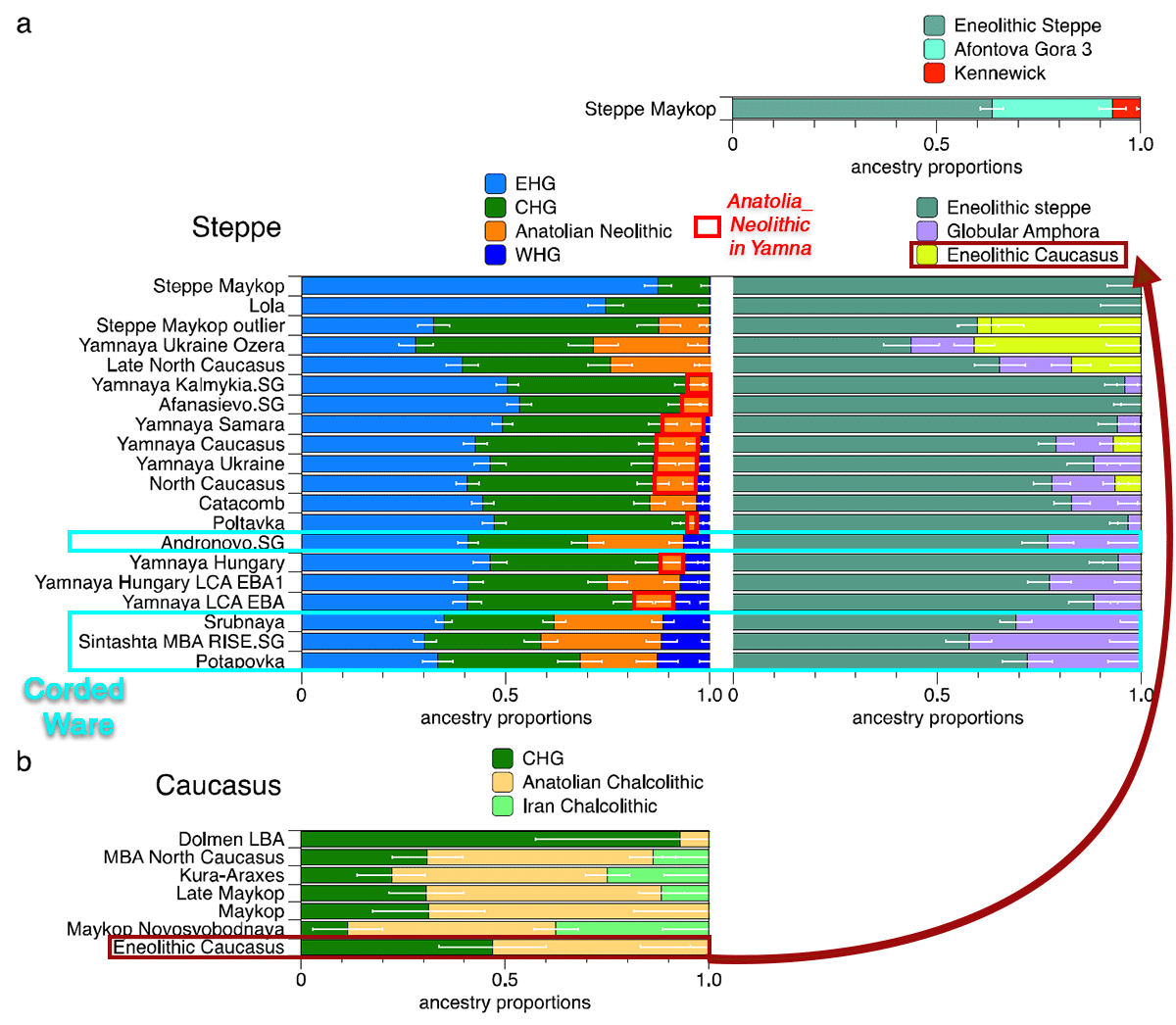

We focused on model of mixture of proximal sources such as CHG and Anatolian Chalcolithic for all six groups of the Caucasus cluster (Eneolithic Caucasus, Maykop and Late Makyop, Maykop-Novosvobodnaya, Kura-Araxes, and Dolmen LBA), with admixture proportions on a genetic cline of 40-72% Anatolian Chalcolithic related and 28-60% CHG related (Supplementary Table 7). When we explored Romania_EN and Greece_Neolithic individuals as alternative southeast European sources (30-46% and 36-49%), the CHG proportions increased to 54-70% and 51-64%, respectively. We hypothesize that alternative models, replacing the Anatolian Chalcolithic individual with yet unsampled populations from eastern Anatolia, South Caucasus or northern Mesopotamia, would probably also provide a fit to the data from some of the tested Caucasus groups.

Also:

The first appearance of ‘Near Eastern farmer related ancestry’ in the steppe zone is evident in Steppe Maykop outliers. However, PCA results also suggest that Yamnaya and later groups of the West Eurasian steppe carry some farmer related ancestry as they are slightly shifted towards ‘European Neolithic groups’ in PC2 (Fig. 2D) compared to Eneolithic steppe. This is not the case for the preceding Eneolithic steppe individuals. The tilting cline is also confirmed by admixture f3-statistics, which provide statistically negative values for AG3 as one source and any Anatolian Neolithic related group as a second source

Detailed exploration via D-statistics in the form of D(EHG, steppe group; X, Mbuti) and D(Samara_Eneolithic, steppe group; X, Mbuti) show significantly negative D values for most of the steppe groups when X is a member of the Caucasus cluster or one of the Levant/Anatolia farmer-related groups (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). In addition, we used f- and D-statistics to explore the shared ancestry with Anatolian Neolithic as well as the reciprocal relationship between Anatolian- and Iranian farmer-related ancestry for all groups of our two main clusters and relevant adjacent regions (Supplementary Fig. 4). Here, we observe an increase in farmer-related ancestry (both Anatolian and Iranian) in our Steppe cluster, ranging from Eneolithic steppe to later groups. In Middle/Late Bronze Age groups especially to the north and east we observe a further increase of Anatolian farmer related ancestry consistent with previous studies of the Poltavka, Andronovo, Srubnaya and Sintashta groups and reflecting a different process not especially related to events in the Caucasus.

(…) Surprisingly, we found that a minimum of four streams of ancestry is needed to explain all eleven steppe ancestry groups tested, including previously published ones (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table 12). Importantly, our results show a subtle contribution of both Anatolian farmer-related ancestry and WHG-related ancestry (Fig.4; Supplementary Tables 13 and 14), which was likely contributed through Middle and Late Neolithic farming groups from adjacent regions in the West. The discovery of a quite old AME ancestry has rendered this probably unnecessary, because this admixture from an Anatolian-like ghost population could be driven even by small populations from the Caucasus.

NOTE. For a detailed account of the possibilities regarding this differential admixture in the North Pontic area in contrast to the Don-Volga-Ural region, you can read the posts Sredni Stog, Proto-Corded Ware, and their “steppe admixture”, and Corded Ware culture origins: The Final Frontier.

While it is not yet fully clear, the increased Anatolian_Neolithic-like ancestry in Ukraine_Eneolithic samples (see below) makes it unlikely that all such ancestry in Corded Ware groups comes from a GAC-related contribution. It is likely that at least part of it represents contributions from populations of the Caucasus, based on the mostly westward population movements in the steppe from ca. 4600 BC on, including the Suvorovo-Novodanilovka expansion, and especially the Kuban-Maykop expansion during the final Eneolithic into the North Pontic area.

NOTE. Since CHG-like groups from the Caucasus may have combinations of AME and ANE ancestry similar to Yamna (which may thus appear as ‘steppe ancestry’ in the North Pontic area), it is impossible to interpret with precision the following ADMIXTURE graphic:

North-Eastern Technocomplex

The East Asian contribution to samples from the WHG samples (like Loschbour or La Braña), as specified in Fu et al. (2016), does not seem to be related to Baikal_EN, and appears possibly (in the ADMIXTURE analysis) integrated into he Villabruna component. I guess this implies that the shared alleles with East Asians are quite early, and potentially due to the expansion of R1b-L754 from the East.

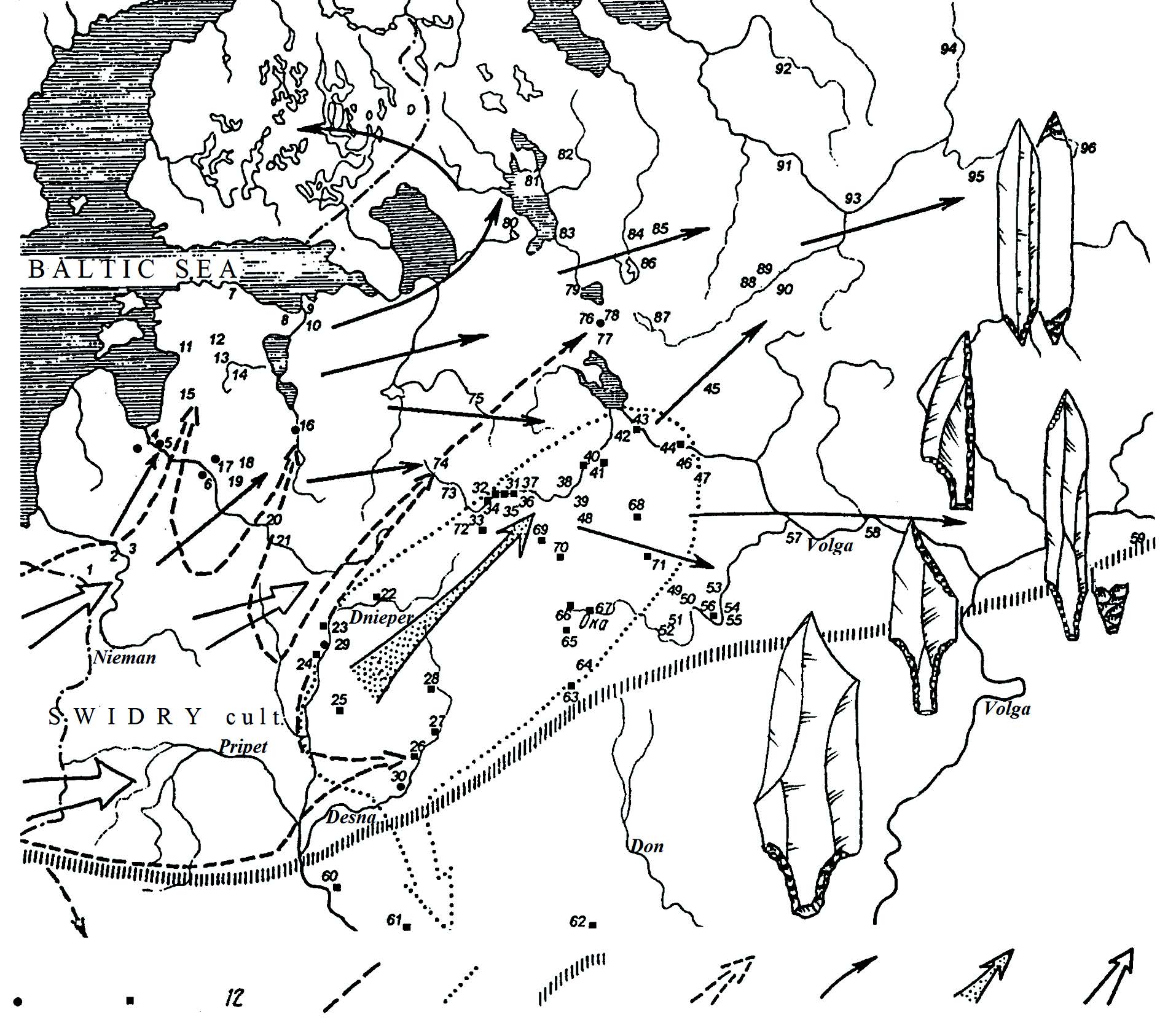

It would be interesting to know the specific material culture Sidelkino belonged to – i.e. if it was related to the expansion of the North-Eastern Technocomplex – , and its Y-DNA. The Post-Swiderian expansion into eastern Europe, probably associated with the expansion of R1b-P297 lineages (including R1b-M73, found later in Botai and in Baltic HG) is supposed to have begun during the 11th millennium BC, but migrations to the Urals and beyond are probably concentrated in the 9th millennium, so this sample is possibly slightly early for R1b.

NOTE. User Rozenfeld at Anthrogenica posted this, which I think is interesting (in case anyone wants to try a Y-SNP call):

there is something strange with Sidelkino EHG: first, its archaeological context is not described in the supplementary. Second, its sex is not listed in the supplementary tables. Third, after looking for info about this sample, I found that: “Сиделькино-3. Для снятия вопроса о половой принадлежности индивида была проведена генетическая экспертиза, выявившая принадлежность останков мужчине.”(translation: Sidelkino-3. To resolve the question about sex of the remains, the genetic analysis was conducted, which showed that remains belonged to male), source: http://static.iea.ras.ru/books/7487_Traditsii.pdf

So either they haven’t mentioned his Y-DNA in the paper for some reason, or there are more than one Sidelkino sample and the male one has not yet been published. The coverage of the Sidelkino sample from the paper is 2.9, more than enough to tell Y-DNA haplogroup.

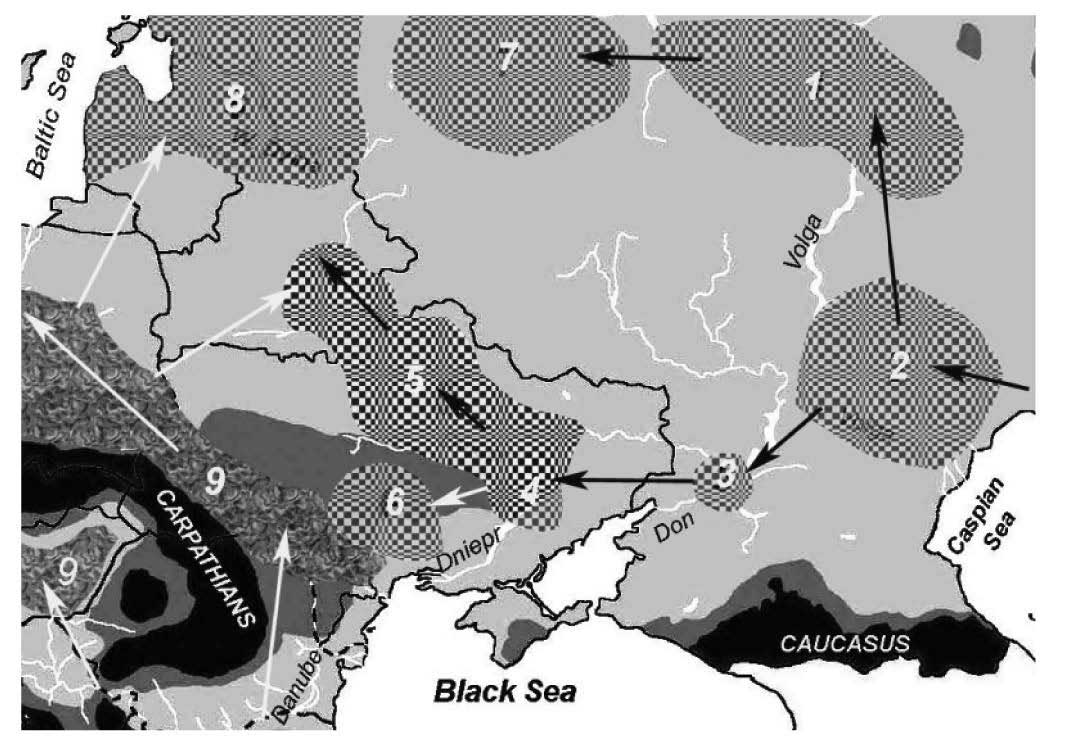

My speculative guess right now about specific population movements in far eastern Europe, based on the few data we have:

- The expansion of the North-Eastern Technocomplex first around the 9th millennium BC, most likely expanded R1b-P279 ca. 11300 BC, judging by its TMRCA, with both R1b-M73 (TMRCA 5300) and R1b-M269 (TMRCA 4400 BC) info (with extra El Mirón ancestry) back, and thus Eurasiatic.

- The expansion of haplogroup J1 to the north may have happened before or after the R1b-P279 expansion. Judging by the increase in AG3-related ancestry near Karelia compared to Baltic_HG, it is possible that it expanded just after R1b-P279 (hence possibly J1-Y6304? TMRCA 9700 BC). Its long-lasting presence in the Caucasus is supported by the Satsurblia (ca. 11300 BC) and the Dolmen BA (ca. 1300 BC) samples.

- The expansion of R1a-M17 ca. 6600 BC is still likely to have happened from the east, based on the R1a-M17 samples found in Baikalic cultures slightly later (ca. 5300 BC). The presence of elevated Baikal_EN ancestry in Karelia HG and in Samara HG, and the finding of R1a-M417 samples in the Forest Zone after the Mesolithic suggests a connection with the expansion of Hunter-Gatherer pottery, from the Elshanka culture in the Samara region northward into the Forset Zone and westward into the North Pontic area.

- The expansion of R1b-M73 ca. 5300 BC is likely to be associated with the emergence of a group east of the Urals (related to the later Botai culture, and potentially Pre-Yukaghir). Its presence in a Narva sample from Donkalnis (ca. 5200 BC) suggest either an early split and spread of both R1b-P297 lineages (M73 and M269) through Eastern Europe, or maybe a back-migration with hunter-gatherer pottery.

- R1b-M269 spread successfully ca. 4400 BC (and R1b-L23 ca. 4100 BC, both based on TMRCA), and this successful expansion is probably to be associated with the Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka expansion. We already know that Samara_HG ca. 5600 was R1b1a, so it is likely that R1b-M269 appeared (or ‘resurged’) in the Volga-Ural region shortly after the expansion of R1a-M17, whose expansion through the region may be inferred by the additional AG3 and Baikal_EN ancestry. Interesting from Samara_HG compared to the previous Sidelkino sample is the introduction of more El Mirón-related ancestry, typical of WHG populations (and thus proper of Baltic groups).

NOTE. The TMRCA dates are obviously gross approximations, because a) the actual rate of mutation is unknown and b) TMRCA estimates are based on the convergence of lineages that survived. The potential finding of R1a-Z645 (possibly Z93+) in Ukraine Eneolithic (ca. 4000 BC), and the potential finding of R1b-L23 in Khvalynsk ca. 4250 BC complicates things further, in terms of dates and origins of any subclade.

The question thus remains as it was long ago: did R1b-M269 lineages expand (‘return’) from the east, near the Urals, or directly from the north? Were they already near Samara at the same time as the expansion of hunter-gatherer pottery, and were not much affected by it? Or did they ‘resurge’ from populations admixed with Caucasus-related ancestry after the expansion of R1a-M17 with this pottery (since there are different stepped expansions from the Samara region)? We could even ask, did R1a-M17 really expand from the east, i.e. are the dates on Baikalic subclades from Moussa et al. (2016) reliable? Or did R1a-M17 expand from some pockets in the Pontic-Caspian steppe, taking over the expansion of HG pottery at some point?

Maglemose-related migrations

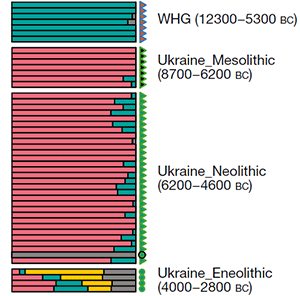

The most interesting aspect from the new paper (regarding Indo-Uralic migrations) is that Ancestral Middle Easterner ancestry will probably be a better proxy for the Anatolia_Neolithic component found in Ukraine Mesolithic to Eneolithic, and possibly also for some of the “more CHG-like” component found among Pontic-Caspian steppe populations, all likely derived from different admixture events with groups from the Caucasus.

NOTE. Even the supposed gene flow of Neolithic Iranian ancestry into the Caucasus can be put into question, since that means possibly a Dzudzuana-like population with greater “deep ancestry” proportion than the one found in CHG, which may still be found within the Caucasus.

If it was not clear already that following ‘steppe ancestry’ wherever it appears is a rather lame way of following Indo-European migrations, every single sample from the Caucasus and their admixture with Pontic-Caspian steppe populations will probably show that “steppe ancestry” is in fact formed by a variety of steppe-related ancestral components, impossible to follow coherently with a single population. Exactly what is happening already with the Siberian ancestry.

If the paper on the Dzudzuana samples has shown something, is that the expansion of an ANE-like population shook the entire Caucasus area up to the Zagros Mountains, creating this ANE – AME cline that are CHG and Iran_N, with further contributions of “deep ancestries” (probably from the south) complicating the picture further.

If this happens with few known samples, and we know of an ANE-like ghost population in the Caucasus (appearing later in the Lola culture), we can already guess that the often repeated “CHG component” found in Ukraine_Eneolithic and Khvalynsk will not be the same (except the part mediated by the Novodanilovka expansion).

This ANE-like expansion happened probably in the Late Upper Palaeolithic, and reached Northern Europe probably after the expansion of the Villabruna cluster (ca. 12000 BC), judging by the advance of AG3-like and ENA-like ancestry in later WHG samples.

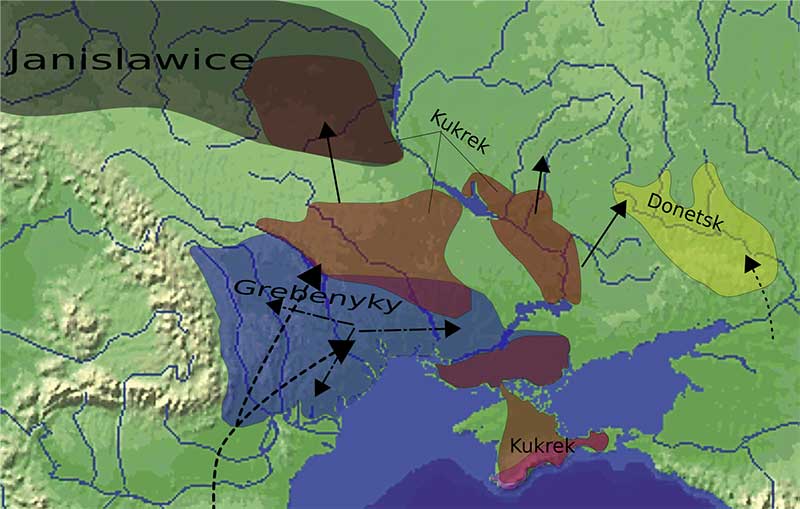

The population movements during the Mesolithic and Early Neolithic in the North Pontic area are quite complicated: the extra AME ancestry is probably connected to the admixture with populations from the Caucasus, while the close similarity of Ukraine populations with Scandinavian ones (with an increase in Villabruna ancestry from Mesolithic to Neolithic samples), probably reveal population movements related to the expansion of Maglemose-related groups.

These Maglemose-related groups were probably migrants from the north-west, originally from the Northern European Plains, who occupied the previous Swiderian territory, and then expanded into the North Pontic area. The overwhelming presence of I2a (likely all I2a2a1b1b) lineages in Ukraine Neolithic supports this migration.

The likely picture of Mesolithic-Neolithic migrations in the North Pontic area right now is then:

- Expansion of R1a-M459 from the east ca. 12000 BC – probably coupled with AG3 and also some Baikal_EN ancestry. First sample is I1819 from Vasilievka (ca. 8700 BC), another is from Dereivka ca. 6900 BC.

- Expansion of R1b-V88 from the Balkans in the west ca. 9700 BC, based on its TMRCA and also the Balkan hunter-gatherer population overwhemingly of this haplogroup from the 10th millennium until the Neolithic. First sample is I1734 from Vasilievka (ca. 7252 BC), which suggests that it replaced the male population there, based on their similar EHG-like adxmixture (and lack of sizeable WHG increase), and shared mtDNA U5b2, U5a2.

- Expansion of I2a-Y5606 probably ca. 6800 based on its TMRCA with Janislawice culture. Supporting this is the increase in WHG contribution to Neolithic samples, including the spread of U4 subclades compared to the previous period.

- Expansion of R1a-M17 starting probably ca. 6600 BC in the east (see above).

NOTE. The first sample of haplogroup I appears in the Mesolithic: I1763 (ca. 8100 BC) of haplogroup I2a1, probably related to an older Upper Palaeolithic expansion.

Conclusion

It is becoming more and more clear with each new paper that – unless the number of very ancient samples increases – the use of Y-chromosome haplogroups remains one of the most important tools for academics; this is especially so in the steppes, in light of the diversity found in populations from the Caucasus. A clear example comes from the Yamna – Corded Ware similarities:

After the publication of the 2015 papers, it was likely that Yamna expanded with haplogroup R1b-L23, but it has only become crystal clear that Yamna expanded through the steppes into Bell Beakers, now that we have data about the strict genetic homogeneity of the whole Yamna population from west to east (including Afanasevo), in contrast with contemporary Corded Ware peoples which expanded from a different forest-steppe population.

The presence of haplogroups Q and R1a-M459 (xM17) in Khvalynsk along with a R1b1a sample, which some interpreted as being akin to modern ‘mixed’ populations in the past, is likely to point instead to a period of Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka expansion with R1b-M269, where different small populations from the steppe were being integrated into the common Khvalynsk stock, but where differences are seen in material culture surrounding their burials, as supported by the finding of R1b1 in the Kuban area already in the first half of the 5th millennium. The case would be similar to the early ‘mixed’ Icelandic population.

Only after the emergence of the Samara culture (in the second half of the 6th millennium BC), with a sample of haplogroup R1b1a, starts then the obvious connection with Early Proto-Indo-Europeans; and only after the appearance of late Sredni Stog and haplogroup R1a-M417 (ca. 4000 BC) is its connection with Uralic also clear. In previous population movements, I think more haplogroups were involved in migrations of small groups, and only some communities among them were eventually successful, expanding to be dominant, creating ever growing cultures during their expansions.

Indeed, if you think in terms of Uralic and Indo-European just as converging languages, and forget their potential genetic connection, then the genetic + linguistic picture becomes simplified, and the upper frontier of the 6th millennium BC with a division North Pontic (Mariupol) vs. Volga-Ural (Samara) is enough. However, tracing their movements backwards – with cultural expansions from west to east (with the expansion of farming), and earlier east to west (with hunter-gatherer pottery), and still earlier west to east (with the north-eastern technocomplex), offers an interesting way to prove their potential connection to macrofamilies, at least in terms of population movements.

I am quite convinced right now that it would be possible to connect the expansion of R1b-L754 subclades with a speculative Nostratic (given the R1b-V88 connection with Afroasiatic, and the obvious connection of R1b-L297 with Eurasiatic). Paradoxically, the connection of an Indo-Uralic community in the steppes (after the separation of Yukaghir) with any lineage expansion (R1a-M17, R1b-M269, or even Q, I or J1) seems somehow blurrier than one year ago, possibly just because there are too many open possibilities.

David Reich says about the admixture with Neanderthals, which he helped discover:

At the conclusion of the Neanderthal genome project, I am still amazed by the surprises we encountered. Having found the first evidence of interbreeding between Neanderthals and modern humans, I continue to have nightmares that the finding is some kind of mistake. But the data are sternly consistent: the evidence for Neanderthal interbreeding turns out to be everywhere. As we continue to do genetic work, we keep encountering more and more patterns that reflect the extraordinary impact this interbreeding has had on the genomes of people living today.

I think this is a shared feeling among many of us who have made proposals about anything, to fear that we have made a gross, evident mistake, and constantly look for flaws. However, it seems to me that geneticists are more preoccupied with being wrong in their developed statistical methods, in the theoretical models they are creating, and not so much about errors in the true ancient ethnolinguistic picture human population genetics is (at least in theory) concerned about. Their publications are, after all, constantly associating genetic finds with cultures and (whenever possible) languages, so this aspect of their research should not be taken lightly.

Seeing how David Anthony or Razib Khan (among many others) have changed their previously preferred migration models as new data was published, and they continue to be respected in their own fields, I guess we can be confident that professionals with integrity are going to accept whatever new picture appears. While I don’t think that genetic finds can change what we can reconstruct with comparative grammar, I am also ready to revise guesstimates and routes of expansion of certain dialects if R1a-Z645 is shown to have accompanied Late Proto-Indo-Europeans during their expansion with Yamna, and later integrated somehow with Corded Ware.

However, taking into account the obsession of some with an ancestral, uninterrupted R1a—Indo-European association, and the lack of actual political repercussion of Neanderthal admixture, I think the most common nightmare that all genetic researchers should be worried about is to keep inflating this “Yamnaya ancestry”-based hornet’s nest, which has been constantly stirred up for the past two years, by rejecting it – or, rather, specifying it into its true complex nature.

This succession of corrections and redefinitions, coupled with the distinct Y-DNA bottleneck of each steppe population, will eventually lead to a completely different ethnolinguistic picture of the Pontic-Caspian region during the Eneolithic, which is likely to eventually piss off not only reasonable academics stubbornly attached to the CWC-IE idea, but also a part of those interested in daydreaming about their patrilineal ancestors.

Sometimes it’s better to just rip off the band-aid once and for all…

Featured image from The oldest pottery in hunter-gatherer communitiesand models of Neolithisation of Eastern Europe (2015), by Andrey Mazurkevich and Ekaterina Dolbunova.

Related

Interesting is today’s post in Ancient DNA Era: Is Male-driven Genetic Replacement always meaning Language-shift?

- Steppe and Caucasus Eneolithic: the new keystones of the EHG-CHG-ANE ancestry in steppe groups

- On the origin of haplogroup R1b-L51 in late Repin / early Yamna settlers

- On the origin and spread of haplogroup R1a-Z645 from eastern Europe

- Corded Ware culture origins: The Final Frontier

- Sredni Stog, Proto-Corded Ware, and their “steppe admixture”

- Kurgan origins and expansion with Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka chieftains

- About Scepters, Horses, and War: on Khvalynsk migrants in the Caucasus and the Danube

- The Caucasus a genetic and cultural barrier; Yamna dominated by R1b-M269; Yamna settlers in Hungary cluster with Yamna

- The concept of “Outlier” in Human Ancestry (III): Late Neolithic samples from the Baltic region and origins of the Corded Ware culture

- Consequences of Damgaard et al. 2018 (II): The late Khvalynsk migration waves with R1b-L23 lineages

- On the potential origin of Caucasus hunter-gatherer ancestry in Eneolithic steppe cultures

- North Pontic steppe Eneolithic cultures, and an alternative Indo-Slavonic model

- New Ukraine Eneolithic sample from late Sredni Stog, near homeland of the Corded Ware culture

- The renewed ‘Kurgan model’ of Kristian Kristiansen and the Danish school: “The Indo-European Corded Ware Theory”