Interesting new paper (behind paywall) Megalakes in the Sahara? A Review, by Quade et al. (2018).

Abstract (emphasis mine):

The Sahara was wetter and greener during multiple interglacial periods of the Quaternary, when some have suggested it featured very large (mega) lakes, ranging in surface area from 30,000 to 350,000 km2. In this paper, we review the physical and biological evidence for these large lakes, especially during the African Humid Period (AHP) 11–5 ka. Megalake systems from around the world provide a checklist of diagnostic features, such as multiple well-defined shoreline benches, wave-rounded beach gravels where coarse material is present, landscape smoothing by lacustrine sediment, large-scale deltaic deposits, and in places, tufas encrusting shorelines. Our survey reveals no clear evidence of these features in the Sahara, except in the Chad basin. Hydrologic modeling of the proposed megalakes requires mean annual rainfall ≥1.2 m/yr and a northward displacement of tropical rainfall belts by ≥1000 km. Such a profound displacement is not supported by other paleo-climate proxies and comprehensive climate models, challenging the existence of megalakes in the Sahara. Rather than megalakes, isolated wetlands and small lakes are more consistent with the Sahelo-Sudanian paleoenvironment that prevailed in the Sahara during the AHP. A pale-green and discontinuously wet Sahara is the likelier context for human migrations out of Africa during the late Quaternary.

The whole review is an interesting read, but here are some relevant excerpts:

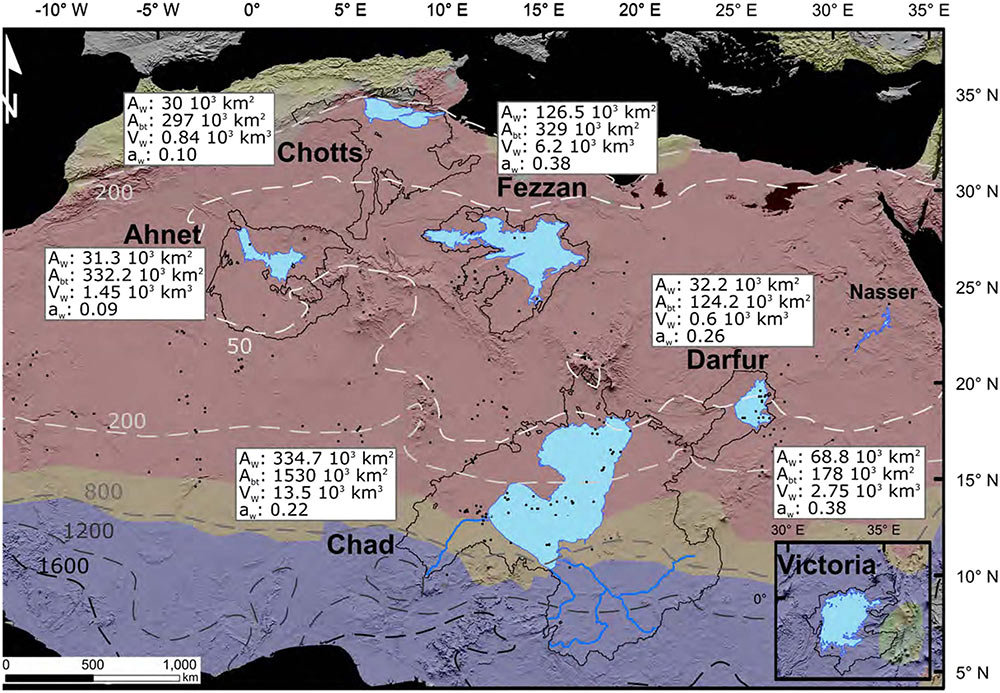

Various researchers have suggested that megalakes coevally covered portions of the Sahara during the AHP and previous periods, such as paleolakes Chad, Darfur, Fezzan, Ahnet-Mouydir, and Chotts (Fig. 2, Table 2). These proposed paleolakes range in size by an order of magnitude in surface area from the Caspian Sea–scale paleo-Lake Chad at 350,000 km2 to Lake Chotts at 30,000 km2. At their maximum, megalakes would have covered ~ 10% of the central and western Sahara, similar to the coverage by megalakes Victoria, Malawi, and Tanganyika in the equatorial tropics of the African Rift today. This observation alone should raise questions of the existence of megalakes in the Sahara, and especially if they developed coevally. Megalakes, because of their significant depth and area, generate large waves that become powerful modifiers of the land surface and leave conspicuous and extensive traces in the geologic record.

Lakes, megalakes, and wetlands

Active ground-water discharge systems abound in the Sahara today, although they were much more widespread in the AHP. They range from isolated springs and wet ground in many oases scattered across the Sahara (e.g., Haynes et al., 1989) to wetlands and small lakes (Kröpelin et al., 2008). Ground water feeding these systems is dominated by fossil AHP-age and older water (e.g., Edmunds and Wright 1979; Sonntag et al., 1980), although recently recharged water (<50 yr) has been locally identified in Saharan ground water (e.g., Sultan et al., 2000; Maduapuchi et al., 2006).

Megalake Chad

In our view, Lake Chad is the only former megalake in the Sahara firmly documented by sedimentologic and geomorphic evidence. Mega-Lake Chad is thought to have covered ~ 345,000 km2, stretching for nearly 8° (10–18°N) of latitude (Ghienne et al., 2002) (Fig. 2). The presence of paleo- Lake Chad was at one point challenged, but several—and in our view very robust—lines of evidence have been presented to support its development during the AHP. These include: (1) clear paleo-shorelines at various elevations, visible on the ground (Abafoni et al., 2014) and in radar and satellite images (Schuster et al., 2005; Drake and Bristow, 2006; Bouchette et al., 2010); (2) sand spits and shoreline berms (Thiemeyer, 2000; Abafoni et al., 2014); and (3) evaporites and aquatic fauna such as fresh-water mollusks and diatoms in basin deposits (e.g., Servant, 1973; Servant and Servant, 1983). Age determinations for all but the Holocene history of mega- Lake Chad are sparse, but there is evidence for Mio-Pliocene lake (s) (Lebatard et al., 2010) and major expansion of paleo- Lake Chad during the AHP (LeBlanc et al., 2006; Schuster et al., 2005; Abafoni et al., 2014; summarized in Armitage et al., 2015) up to the basin overflow level at ~ 329m asl.

Insights from hydrologic mass balance of megalakes

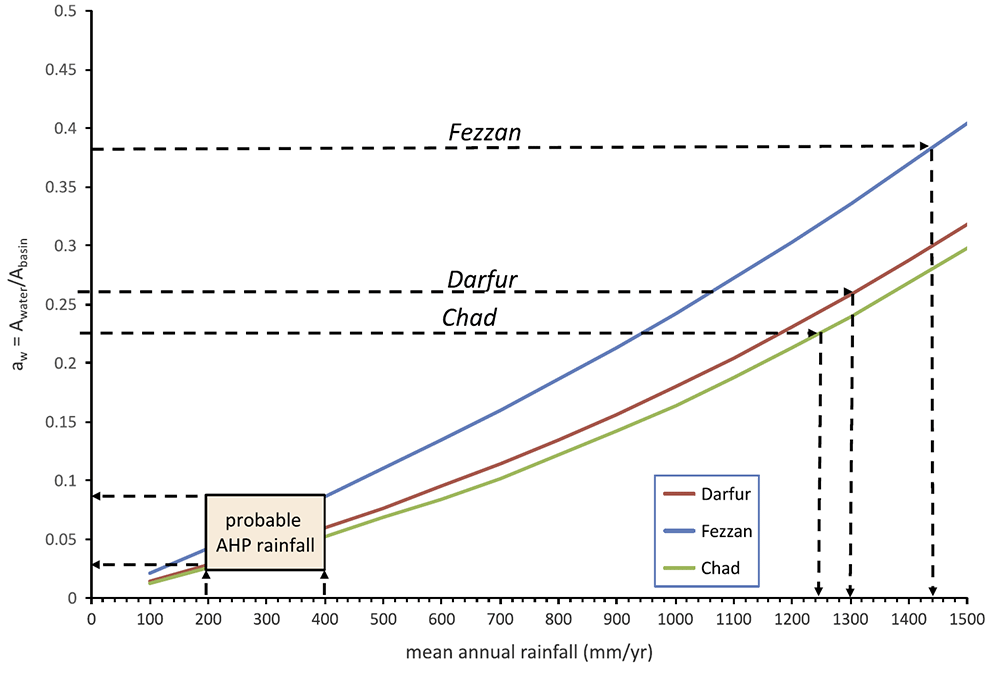

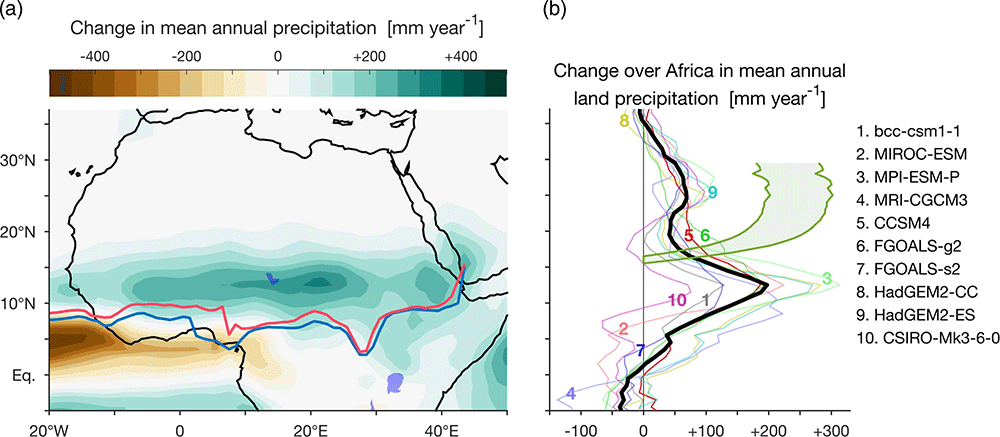

Using these conservative conditions (i.e., erring in the direction that will support megalake formation), our hydrologic models for the two biggest central Saharan megalakes (Darfur and Fezzan) require minimum annual average rainfall amounts of ~ 1.1 m/yr to balance moisture losses from their respective basins (Supplementary Table S1). Lake Chad required a similar amount (~1 m/yr; Supplementary Table S1) during the AHP according to our calculations, but this is plausible, because even today the southern third of the Chad basin receives ≥1.2 m/yr (Fig. 2) and experiences a climate similar to Lake Victoria. A modest 5° shift in the rainfall belt would bring this moist zone northward to cover a much larger portion of the Chad basin, which spans N13° ±7°. Estimated rainfall rates for Darfur and Fezzan are slightly less than the average of ~ 1.3 m/yr for the Lake Victoria basin, because of the lower aw values, that is, smaller areas of Saharan megalakes compared with their respective drainage basins (Fig. 15).

Estimates of paleo-rainfall during the AHP

Here major contradictions develop between the model outcomes and paleo-vegetation evidence, because our Sahelo-Sudanian hydrologic model predicts wetter conditions and therefore more tropical vegetation assemblages than found around Lake Victoria today. In fact, none of the very wet rainfall scenarios required by all our model runs can be reconciled with the relatively dry conditions implied by the fossil plant and animal evidence. In short, megalakes cannot be produced in Sahelo-Sudanian conditions past or present; to form, they require a tropical or subtropical setting, and major displacements of the African monsoon or extra-desert moisture sources.

Conclusions

If not megalakes, what size lakes, marshes, discharging springs, and flowing rivers in the Sahara were sustainable in Sahelo-Sudanian climatic conditions? For lakes and perennial rivers to be created and sustained, net rainfall in the basin has to exceed loss to evapotranspiration, evaporation, and infiltration, yielding runoff that then supplies a local lake or river. Our hydrologic models (see Supplementary Material) and empirical observations (Gash et al., 1991; Monteith, 1991) for the Sahel suggest that this limit is in the 200–300 mm/yr range, meaning that most of the Sahara during the AHP was probably too dry to support very large lakes or perennial rivers by means of local runoff. This does not preclude creation of local wetlands supplied by ground-water recharge focused from a very large recharge area or forced to the surface by hydrologic barriers such as faults, nor megalakes like Chad supplied by moisture from the subtropics and tropics outside the Sahel. But it does raise a key question concerning the size of paleolakes, if not megalakes, in the Sahara during the AHP. Our analysis suggests that Sahelo-Sudanian climate could perhaps support a paleolake approximately ≤5000 km2 in area in the Darfur basin and ≤10,000–20,000 km2 in the Fezzan basin. These are more than an order of magnitude smaller than the megalakes envisioned for these basins, but they are still sizable, and if enclosed in a single body of water, should have been large enough to generate clear shorelines (Enzel et al., 2015, 2017). On the other hand, if surface water was dispersed across a series of shallow and extensive but partly disconnected wetlands, as also implied by previous research (e.g., Pachur and Hoelzmann, 1991), then shorelines may not have developed.

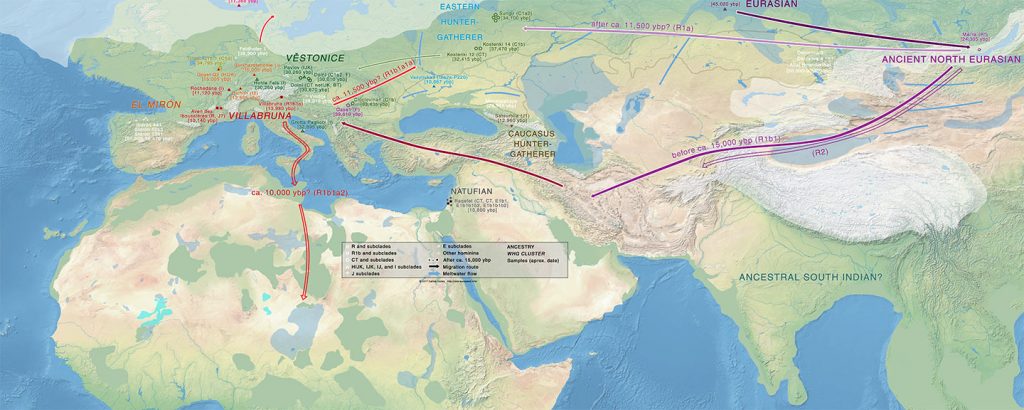

One of the underdeveloped ideas of my Indo-European demic diffusion model was that R1b-V88 had migrated through South Italy to Northern Africa, and from it using the Sahara Green Corridor to the south, from where the “upside-down” view of Bender (2007) could have occurred, i.e. Afroasiatic expanding westwards within the Green Sahara, precisely at this time, and from a homeland near the Megalake Chad region (see here).

Whether or not R1b-V88 brought the ‘original’ lineage that expanded Afroasiatic languages may be contended, but after D’Atanasio et al. (2018) it seems that only two lineages, E-M2 and R1b-V88, fit the ‘star-like’ structure suggesting an appropriate haplogroup expansion and necessary regional distribution that could explain the spread of Afroasiatic languages within a reasonable time frame.

This review shows that the hypothesized Green Sahara corridor full of megalakes that some proposed had fully connected Africa from west to east was actually a strip of Sahelo-Sudanian steppe spread to the north of its current distribution, including the Chad megalake, East Africa and Arabia, apart from other discontinuous local wetlands further to the north in Africa. This greenish belt would have probably allowed for the initial spread of early Afroasiatic proto-languages only through the southern part of the current Sahara Desert. This and the R1b-V88 haplogroup distribution in Central and North Africa (with a prevalence among Chadic speakers probably due to later bottlenecks), and the Near East, leaves still fewer possibilities for an expansion of Afroasiatic from anywhere else.

If my proposal turns out to be correct, this Afroasiatic-like language would be the one suggested by some in the vocabulary of Old European and North European local groups (viz. Kroonen for the Agricultural Substrate Hypothesis), and not Anatolian farmer ancestry or haplogroup G2, which would have been rather confined to Southern Europe, mainly south of the Loess line, where incoming Middle East farmers encountered the main difficulties spreading agriculture and herding, and where they eventually admixed with local hunter-gatherers.

NOTE. If related to attested languages before the Roman expansion, Tyrsenian would be a good candidate for a descendant of the language of Anatolian farmers, given the more recent expansion of Anatolian ancestry to the Tuscan region (even if already influenced by Iran farmer ancestry), which reinforces its direct connection to the Aegean.

The fiercest opposition to this R1b-V88 – Afroasiatic connection may come from:

- Traditional Hamito-Semitic scholars, who try to look for any parent language almost invariably in or around the Near East – the typical “here it was first attested, ergo here must be the origin, too”-assumption (coupled with the cradle of civilization memes) akin to the original reasons behind Anatolian or Out-of-India hypotheses; and of course

- autochthonous continuity theories based on modern subclades, of (mainly Semitic) peoples of haplogroup E or J, who will root for either one or the other as the Afroasiatic source no matter what. As we have seen with the R1a – Indo-European hypothesis (see here for its history), this is never the right way to look at prehistoric migrations, though.

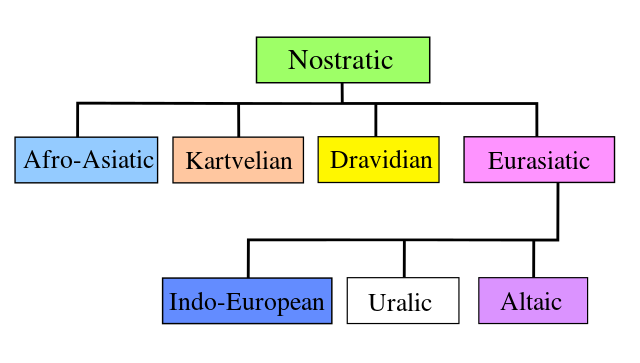

I proposed that it was R1a-M417 the lineage marking an expansion of Indo-Uralic from the east near Lake Baikal, then obviously connected to Yukaghir and Altaic languages marked by R1a-M17, and that haplogroup R could then be the source of a hypothetic Nostratic expansion (where R2 could mark the Dravidian expansion), with upper clades being maybe responsible for Borean.

However, recent studies have shown early expansions of R1b-297 to East Europe (Mathieson et al. 2017 & 2018), and of R1b-M73 to East Eurasia probably up to Siberia, and possibly reaching the Pacific (Jeong et al. 2018). Also, the Steppe Eneolithic and Caucasus Eneolithic clusters seen in Wang et al. (2018) would be able to explain the WHG – EHG – ANE ancestry cline seen in Mesolithic and Neolithic Eurasia without a need for westward migrations.

Dravidian is now after Narasimhan et al. (2018) and Damgaard et al. (Science 2018) more and more likely to be linked to the expansion of the Indus Valley civilization and haplogroup J, in turn strongly linked to Iranian farmer ancestry, thus giving support to an Elamo-Dravidian group stemming from Iran Neolithic.

NOTE. This Dravidian-IVC and Iran connection has been supported for years by knowledgeable bloggers and commenters alike, see e.g. one of Razib Khan’s posts on the subject. This rather early support for what is obvious today is probably behind the reactionary views by some nationalist Hindus, who probably saw in this a potential reason for a strengthened Indo-Aryan/Dravidian divide adding to the religious patchwork that is modern India.

I am not in a good position to judge Nostratic, and I don’t think Glottochronology, Swadesh lists, or any statistical methods applied to a bunch of words are of any use, here or anywhere. The work of pioneers like Illich-Svitych or Starostin, on the other hand, seem to me solid attempts to obtain a faithful reconstruction, if rather outdated today.

NOTE. I am still struggling to learn more about Uralic and Indo-Uralic; not because it is more difficult than Indo-European, but because – in comparison to PIE comparative grammar – material about them is scarce, and the few available sources are sometimes contradictory. My knowledge of Afroasiatic is limited to Semitic (Arabic and Akkadian), and the field is not much more developed here than for Uralic…

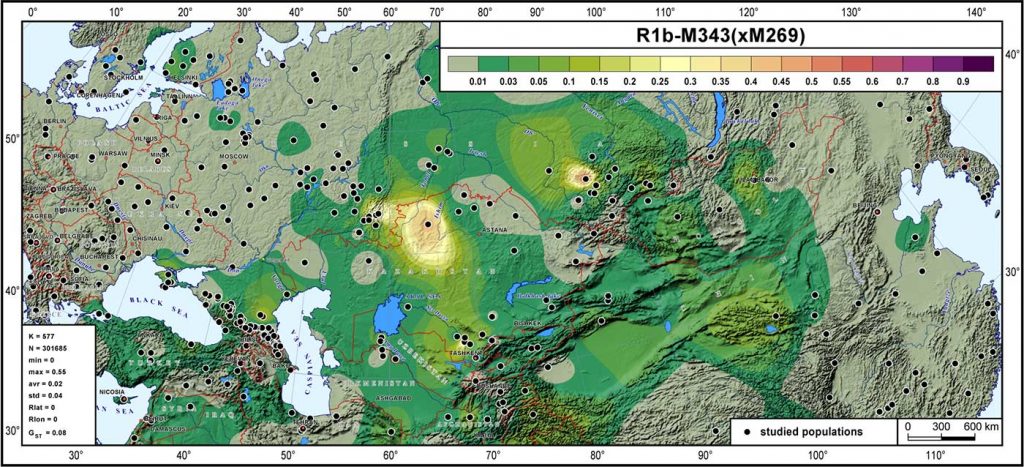

If one wanted to support a Nostratic proto-language, though, and not being able to take into account genome-wide autosomal admixture, the only haplogroup right now which can connect the expansion of all its branches is R1b-M343:

- R1b-L278 expanded from Asia to Europe through the Iranian Plateau, since early subclades are found in Iran and the Caucasus region, thus supporting the separation of Elamo-Dravidian and Kartvelian branches;

- From the Danube or another European region ‘near’ the Villabruna 1 sample (of haplogroup R1b-L754):

- R1b-V88 expanding everywhere in Europe, and especially the branch expanding to the south into Africa, may be linked to the initial Afroasiatic expansion through the Pale-Green Sahara corridor (and even a hypothetic expansion with E-M2 subclades and/or from the Middle East would also leave open the influence of V88 and previous R1b subclades from the Middle East in the emergence of the language);

- R1b-297 subclades expanding to the east may be linked to Eurasiatic, giving rise to both Indo-Uralic (M269) and Macro- or Micro-Altaic (M73) expansions.

This is shameless, simplistic speculation, of course, but not more than the Nostratic hypothesis, and it has the main advantage of offering ‘small and late’ language expansions relative to other proposals spanning thousands (or even tens of thousands) of years more of language separation. On the other hand, that would leave Borean out of the question, unless the initial expansion of R1b subclades happened from a community close to lake Baikal (and Mal’ta) that was also at the origin of the other supposedly related Borean branches, whether linked to haplogroup R or to any other…

NOTE. If Afroasiatic and Indo-Uralic (or Eurasiatic) are not genetically related, my previous simplistic model, R1b-Afroasiatic vs. R1a-Eurasiatic, may still be supported, with R1a-M17 potentially marking the latest meaningful westward population expansion from which EHG ancestry might have developed (see here). Without detailed works on Nostratic comparative grammar and dialectalization, and especially without a lot more Palaeolithic and Mesolithic samples, all this will remain highly speculative, like proposals of the 2000s about Y-DNA-haplogroup – language relationships.

Related:

- Genetic history of admixture across inner Eurasia; Botai shows R1b-M73

- Steppe and Caucasus Eneolithic: the new keystones of the EHG-CHG-ANE ancestry in steppe groups

- Ancient genomes from North Africa evidence Neolithic migrations to the Maghreb

- Tales of Human Migration, Admixture, and Selection in Africa

- Pleistocene North African genomes link Near Eastern and sub-Saharan African human populations

- Genetic ancestry of Hadza and Sandawe peoples reveals ancient population structure in Africa

- R1b-V88 migration through Southern Italy into Green Sahara corridor, and the Afroasiatic connection

- Potential Afroasiatic Urheimat near Lake Megachad

- Expansion of peoples associated with spread of haplogroups: Mongols and C3*-F3918, Arabs and E-M183 (M81)

- The arrival of haplogroup R1a-M417 in Eastern Europe, and the east-west diffusion of pottery through North Eurasia

- Genetic landscapes showing human genetic diversity aligning with geography

- Human ancestry solves language questions? New admixture citebait