Open access Characterizing the genetic history of admixture across inner Eurasia, by Jeong et al. (2018).

Abstract (emphasis mine):

The indigenous populations of inner Eurasia, a huge geographic region covering the central Eurasian steppe and the northern Eurasian taiga and tundra, harbor tremendous diversity in their genes, cultures and languages. In this study, we report novel genome-wide data for 763 individuals from Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Mongolia, Russia, Tajikistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. We furthermore report genome-wide data of two Eneolithic individuals (~5,400 years before present) associated with the Botai culture in northern Kazakhstan. We find that inner Eurasian populations are structured into three distinct admixture clines stretching between various western and eastern Eurasian ancestries. This genetic separation is well mirrored by geography. The ancient Botai genomes suggest yet another layer of admixture in inner Eurasia that involves Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in Europe, the Upper Paleolithic southern Siberians and East Asians. Admixture modeling of ancient and modern populations suggests an overwriting of this ancient structure in the Altai-Sayan region by migrations of western steppe herders, but partial retaining of this ancient North Eurasian-related cline further to the North. Finally, the genetic structure of Caucasus populations highlights a role of the Caucasus Mountains as a barrier to gene flow and suggests a post-Neolithic gene flow into North Caucasus populations from the steppe.

Interesting excerpts:

On North Eurasians

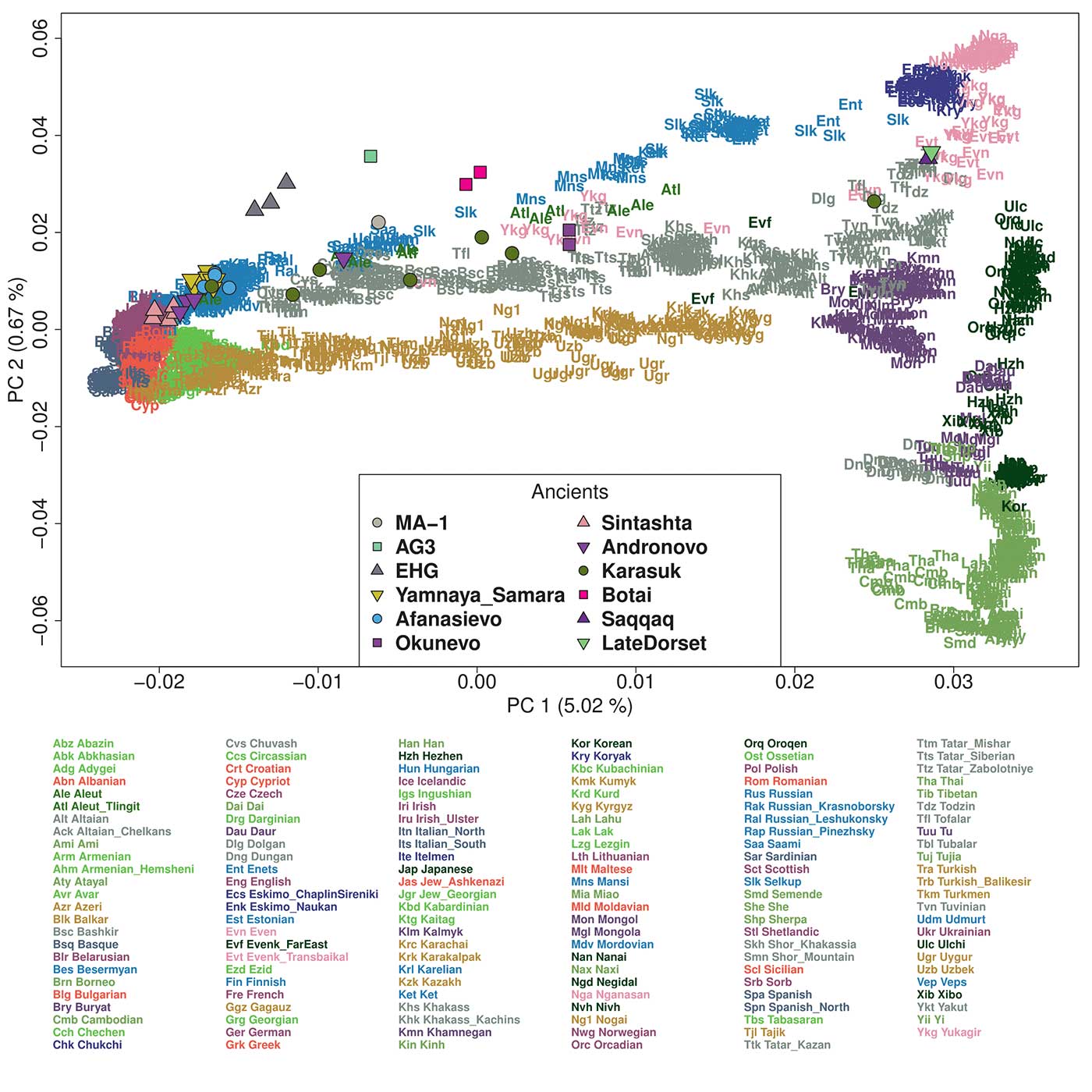

In a PCA of Eurasian individuals, we find that PC1 separates eastern and western Eurasian populations, PC2 splits eastern Eurasians along a north-south cline, and PC3 captures variation in western Eurasians with Caucasus and northeastern European populations at opposite ends (Figure 2A and Figures S1-S2). Inner Eurasians are scattered across PC1 in between, largely reflecting their geographic locations. Strikingly, inner Eurasian populations seem to be structured into three distinct west-east genetic clines running between different western and eastern Eurasian groups, instead of being evenly spaced in PC space. Individuals from northern Eurasia, speaking Uralic or Yeniseian languages, form a cline connecting northeast Europeans and the Uralic (Samoyedic) speaking Nganasans from northern Siberia (“forest-tundra” cline). Individuals from the Eurasian steppe, mostly speaking Turkic and Mongolic languages, are scattered along two clines below the forest-tundra cline. Both clines run into Turkic- and Mongolic-speaking populations in southern Siberia and Mongolia, and further into Tungusic-speaking populations in Manchuria and the Russian Far East in the East; however, they diverge in the west, oneheading to the Caucasus and the other heading to populations of the Volga-308 Ural area (the “southern steppe” and “steppe-forest” clines, respectively; Figure 2 and Figure S2).

(…)

The forest-tundra cline populations derive most of their eastern Eurasian ancestry from a component most enriched in Nganasans, while those on the steppe-forest and southern steppe clines have this component together with another component most enriched in populations from the Russian Far East, such as Ulchi and Nivkh. The southern steppe cline groups are distinct from the others in their western Eurasian ancestry profile, in the sense that they have a high proportion of a component most enriched in Mesolithic Caucasus hunter-gatherers (“CHG”) and Neolithic Iranians (“Iran_N”) and frequently harbor another component enriched in South Asians (Figure S4).

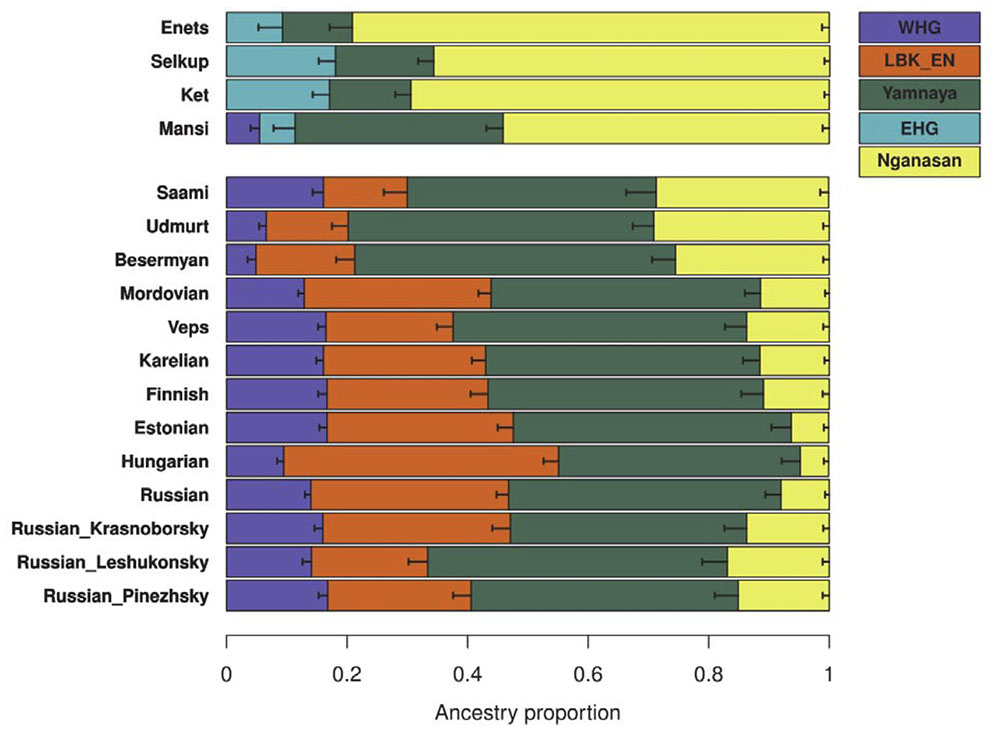

For the forest-tundra cline populations, for which currently no relevant Holocene ancient genomes are available, we took a more generalized approach of using proxies for contemporary Europeans: WHG, WSH (represented by “Yamnaya_Samara”), and early Neolithic European farmers (EEF; represented by “LBK_EN”; Table S2). Adding Nganasans as the fourth reference, we find that most Uralic-speaking populations in Europe (i.e. west of the Urals) and Russians are well modeled by this four-way admixture model (χ 2 p ≥ 0.05 for all but three groups; Figure 5 and Table S8). Nganasan-related ancestry substantially contributes to their gene pools and cannot be removed from the model without a significant decrease in model fit (4.7% to 29.1% contribution; χ 2 p ≤ 1.12×10-8; Table S8). The ratio of contributions from three European references varies from group to group, probably reflecting genetic exchange with neighboring non-Uralic groups. For example, Saami from northern Fennoscandia contain a higher WHG and lower WSH contribution (16.1% and 41.3%, respectively) than Udmurts or Besermyans from the Volga river region do (4.9-6.6% and 50.7-53.2%, respectively), while the three groups have similar amounts of Nganasan-related ancestry (25.5-29.1%).

The Caucasus Mountains form a barrier to gene flow

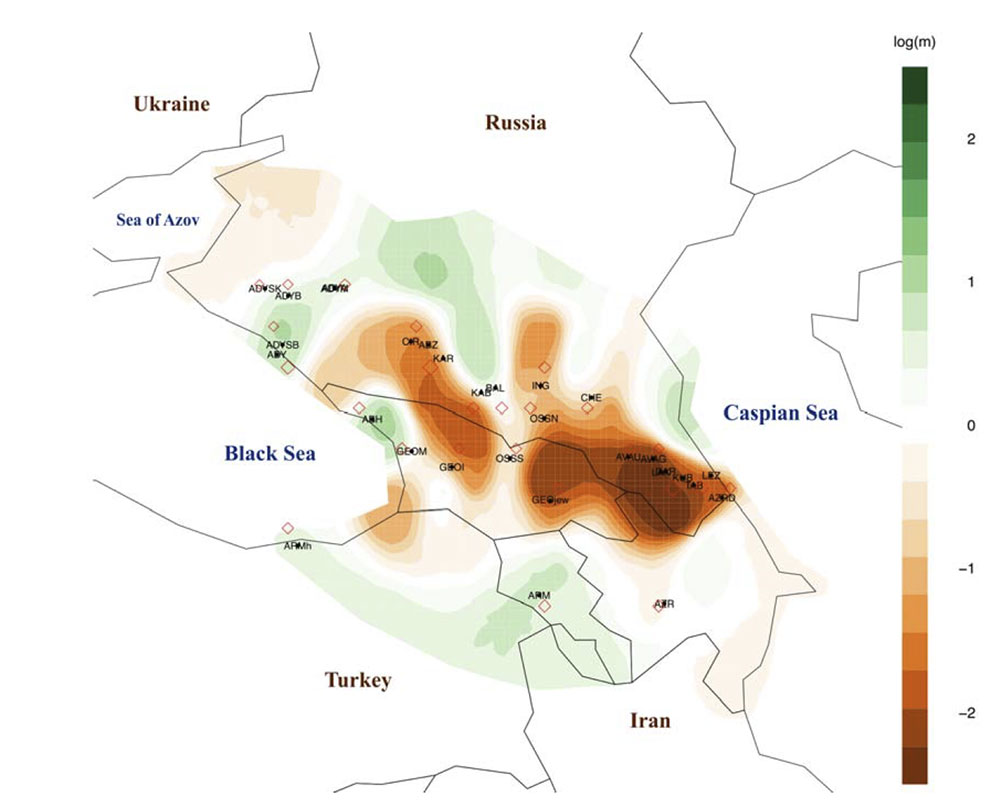

By applying EEMS to the Caucasus region, we identify a strong barrier to gene flow separating North and South Caucasus populations. This genetic barrier coincides with the Greater Caucasus mountain ridge even to small scale: a weaker barrier in the middle, overlapping with Ossetia, matches well with the region where the ridge also becomes narrow. We also observe weak barriers running in the north-south direction that separate northeastern populations from northwestern ones. Together with PCA, EEMS results suggest that the Caucasus Mountains have posed a strong barrier to human migration.

On the Botai individuals

The Y-chromosome of the male Botai individual (TU45) belongs to the haplogroup R1b (Table 411 S6). However, it falls into neither a predominant European branch R1b-L5165 nor into a R1b-GG400 branch found in Yamnaya individuals. Thus, phylogenetically this Botai individual should belong to the R1b-M73 branch which is frequent in the Eurasian steppe (Figure S9). This branch was also found in Mesolithic samples from Latvia as well as in numerous modern southern Siberian and Central Asian groups.

The Botai genomes provide a critical snapshot of the genetic profile of pre-Bronze Age steppe populations. Our admixture modeling positions Botai primarily on an ancient genetic cline of the pre-Neolithic western Eurasian hunter-gatherers: stretching from the post-Ice Age western European hunter-gatherers (e.g. WHG) to EHG in Karelia and Samara to the Upper Paleolithic southern Siberians (e.g. AG3). Botai’s position on this cline, between EHG and AG3, fits well with their geographic location and suggests that ANE-related ancestry in the East did have a lingering genetic impact on Holocene Siberian and Central Asian populations at least till the time of Botai.

(…)

The most recent clear connection with the Botai ancestry can be found in the Middle Bronze Age Okunevo individuals (Figure S6C). In contrast, additional EHG-related ancestry is required to explain the forest-tundra populations to the east of the Urals (Figure 5 and Table S8). Their multi-way mixture model may in fact portrait a prehistoric two-way mixture of a WSH population and a hypothetical eastern Eurasian one that has an ANE-related contribution higher than that in Nganasans. Botai and Okunevo individuals prove the existence of such ANE ancestry-rich populations. Pre-Bronze Age genomes from Siberia will be critical for testing this hypothesis.

So, to sum up:

- Northern Eurasia forms a Uralic – Yeniseian cline from east to west, with contribution from Steppe, WHG, and Siberian ancestry. Siberian ancestry is represented by Palaeo-Siberian Nganasans, who adopted Samoyedic quite late. It was already known that the different waves of Siberian ancestry are too late and do not represent the spread of Uralic languages, so that leaves us with Steppe and WHG.

- The Caucasus Mountains were a long-lasting prehistoric barrier to gene flow (as recently shown in Y-DNA, too).

- The Botai sample (ca. 3632-3100 BC) represents thus the furthest east that R1b-P297 subclades had expanded (we did know that, and that they didn’t have close genetic links with Khvalynsk, so the haplogroup spread there probably much earlier). It expanded R1b-M269’s sister clade R1b-M73 (also found in the Baltic region), and the Botai are on the ‘eastern’ end of an ancient genetic cline stretching from WHG to EHG to Afontova Gora.

EDIT (23 MAY 2018) Both samples share mtDNA, and the male one shares Y-DNA, with those reported in Damgaard et al. (Nature 2018); although dates are slightly different (3371-3354 calBC for BOT 14), it is within the range given for this one; for the female, the dates are similar (3521-3377 calBC for BOT2016, 3517-3367 cal. BCE for this one). The lack of data on their origin may point to the fact that we only have different bone samples from the same two Botai individuals. So probably still 50% R1b-M73 (with the other 50% being N2* from BOT15)…

It seems therefore not only that R1b-M269 is bound to split from the parent haplogroup in or around the steppe or forest-steppe: the Mesolithic spread of haplogroup R1b in North Eurasia is wider and its relevance thus greater than previously thought.

We may need to rethink the role of haplogroup R1a in spreading EHG and Indo-Uralic from east to west…

Featured image, from the supplementary materials: Frequency distribution map of the Y-chromosomal haplogroup R1b-P343(xM269) identified in the Eneolithic Botai individual. All modern Eurasian samples with this haplogroup tested to date for the downstream markers fall into R1b-M73 branch, suggesting Botai sample be one of its earliest representatives.

Related:

- The Caucasus a genetic and cultural barrier; Yamna dominated by R1b-M269; Yamna settlers in Hungary cluster with Yamna

- The Caucasus a genetic and cultural barrier; Yamna dominated by R1b-M269; Yamna settlers in Hungary cluster with Yamna

- Consequences of Damgaard et al. 2018 (I): EHG ancestry in Maykop samples, and the potential Anatolian expansion routes

- Consequences of Damgaard et al. 2018 (II): The late Khvalynsk migration waves with R1b-L23 lineages

- Consequences of Damgaard et al. 2018 (III): Proto-Finno-Ugric & Proto-Indo-Iranian in the North Caspian region

- No large-scale steppe migration into Anatolia; early Yamna migrations and MLBA brought LPIE dialects in Asia

- Eurasian steppe dominated by Iranian peoples, Indo-Iranian expanded from East Yamna

- Early Indo-Iranian formed mainly by R1b-Z2103 and R1a-Z93, Corded Ware out of Late PIE-speaking migrations