New paper (behind paywall) The Expansion of the Indo-European Languages, by Frederik Kortlandt, JIES (2018) 46(1 & 2):219-231.

Abstract:

When considering the way the Indo-Europeans took to the west, it is important to realize that mountains, forests and marshlands were prohibitive impediments. Moreover, people need fresh water, all the more so when traveling with horses. The natural way from the Russian steppe to the west is therefore along the northern bank of the river Danube. This leads to the hypothesis that the western Indo-Europeans represent successive waves of migration along the Danube and its tributaries. The Celts evidently followed the Danube all the way to southern Germany. The ancestors of the Italic tribes, including the Veneti, may have followed the river Sava towards northern Italy. The ancestors of Germanic speakers apparently moved into Moravia and Bohemia and followed the Elbe into Saxony. A part of the Veneti may have followed them into Moravia and moved along the Oder through the Moravian Gate into Silesia. The hypothetical speakers of Temematic probably moved through Slovakia along the river Orava into western Galicia. The ancestors of speakers of Balkan languages crossed the lower Danube and moved to the south. This scenario is in agreement with the generally accepted view of the earliest relations between these branches of Indo-European.

The western Indo-European vocabulary in Baltic and Slavic is the result of an Indo-European substratum which contained an older non-Indo-European layer and was part of the Corded Ware horizon. The numbers show that a considerable part of the vocabulary was borrowed after the split between Baltic and Slavic, which came about when their speakers moved westwards north and south of the Pripet marshes. These events are older than the westward movement of the Slavs which brought them into contact with Temematic speakers. One may conjecture that the Venedi occupied the Oder basin and then expanded eastwards over the larger part of present-day Poland before the western Balts came down the river Niemen and moved onwards to the lower Vistula. We may then identify the Venedic expansion with the spread of the Corded Ware horizon and the westward migration of the Balts and the Slavs with their integration into the larger cultural complex. The theory that the Venedi separated from the Veneti in the upper Sava region and moved through Moravia and Silesia to the Baltic Sea explains the “im Namenmaterial auffällige Übereinstimmung zwischen dem Baltikum und den Gebieten um den Nordteil der Adria” (Udolph 1981: 61). The Balts probably moved in two stages because the differences between West and East Baltic are considerable.

Instead of reinterpreting his views in light of the recent genetic finds, Kortlandt tries to mix in this paper his own old theories (see his paper Baltic, Slavic, Germanic) with the recent interpretations of genetic papers, using also dubious secondary sources – e.g. Iversen and Kroonen (2017) or Klejn (2017) [see here, and here] – which, in my opinion, creates a potentially dangerous circular reasoning.

For example, even though he criticizes the general stance of recent genetic papers with regard to Proto-Indo-European dialectalization and expansion as too early, and he supports the Danube expansion route, he nevertheless follows their interpretations in accepting that Corded Ware was Indo-European (following the newest model proposed by Anthony):

The [Yamnaya] penetrated central and northern Europe from the lower Danube through the Carpathian basin, not from the east. The Carpathian basis was evidently the cradle of the Corded Ware cultures, where the descendants of the Yamnaya mixed with the local early farmers before proceeding to the north. The development has a clear parallel in the Middle Ages, when the Hungarians mixed with the local Slavic populations in the same territory (cf. Kushniarevich & al. 2015).

He still follows his good old Indo-Slavonic group in the east, but at the same time maintains Kallio’s view that there were no early Uralic loanwords in Balto-Slavic, and also Kallio’s (and the general) view that there were close contacts with PIE and Pre-Proto-Indo-Iranian…

NOTE. The latest paper on Eurasian migrations by Damgaard et al. (Nature 2018), which shows mainly Proto-Iranians dominating over East Europe after the Early Bronze Age, have left still fewer space for a Proto-Balto-Slavic group emerging from the east.

Also, he asserts the following, which is a rather weird interpretation of events:

It appears that the Corded Ware horizon spread to southern Scandinavia (cf. Iversen & Kroonen 2017) but not to the Baltic region during the Neolithic.

“However, we also find indications of genetic impact from exogenous populations during the Neolithic, most likely from northern Eurasia and the Pontic Steppe. These influences are distinct from the Anatolian-farmer-related gene flow found in Central Europe during this period.”

It follows that the Indo-Europeans did not reach the Baltic region before the Late Neolithic. The influx of non-local people from northern Eurasia may be identified with the expansion of the Finno-Ugrians, who came into contact with the Indo-Europeans as a result of the eastward expansion of the latter in the fourth millennium. This was long before the split between Balto-Slavic and Indo-Iranian.

In the Late Neolithic there was “a further population movement into the regions surrounding the Baltic Sea” that was “accompanied by the first evidence of extensive animal husbandry in the Eastern Baltic”, which “suggests import of the new economy by an incoming steppe-like population independent of the agricultural societies that were already established to the south and west of the Baltic Sea.” (Mittnik & al. 2018). These may have been the ancestors of Balto-Slavic speakers. At a later stage, the Corded Ware horizon spread eastward, giving rise to farming ancestry in Eastern Baltic individuals and to a female gene-flow from the Eastern Baltic into Central Europe (ibidem).

He is a strong Indo-Uralic supporter, and supports a parallel Indo-European – Uralic development in Eastern Europe, and (as you can read) he misunderstands the description of population movements in the Baltic region, and thus misplaces Finno-Ugric speakers as Eurasian migrants arriving in the Baltic from the east during the Late Neolithic, before the Corded Ware expansion, which is not what the cited papers implied.

NOTE. Such an identification of westward Neolithic migrations with Uralic speakers is furthermore to be rejected following the most recent paper on Fennoscandian samples.

He had previously asserted that the substrate common to Germanic and Balto-Slavic is Indo-European with non-Indo-European substrate influence, so I guess that Corded Ware influencing as a substrate both Germanic and Balto-Slavic is the best way he could put everything together, if one assumes the widespread interpretations of genetic papers:

Thus, I think that the western Indo-European vocabulary in Baltic and Slavic is the result of an Indo-European substratum which contained an older non-Indo-European layer and was part of the Corded Ware horizon. The numbers show that a considerable part of the vocabulary was borrowed after the split between Baltic and Slavic, (…)

NOTE. It is very likely that this paper was sent in late 2017. That’s the main problem with traditional publications including the most recent genetic investigation: by the time something gets eventually published, the text is already outdated.

I obviously share his opinion on precedence of disciplines in Indo-European studies:

The methodological point to be emphasized here is that the linguistic evidence takes precedence over archaeological and genetic data, which give no information about the languages spoken and can only support the linguistic evidence. The relative chronology of developments must be established on the basis of the comparative method and internal reconstruction. The location of a reconstructed language can only be established on the basis of lexical and onomastic material. On the other hand, archaeological or genetic data may supply the corresponding absolute chronology. It is therefore incorrect to attribute cultural influences in southern Scandinavia and the Baltic region in the third millennium to Germanic or Baltic speakers because these languages did not yet exist. While the Italo-Celtic branch may have separated from its Indo-European neighbors in the first half of the third millennium, Proto-Balto-Slavic and Proto-Indo-Iranian can be dated to the second millennium and Proto-Germanic to the end of the first millennium BC (cf. Kortlandt 2010: 173f., 197f., 249f.). The Indo-Europeans who moved to southern Scandinavia as part of the Corded Ware horizon were not the ancestors of Germanic speakers, who lived farther to the south, but belonged to an unknown branch that was eventually replaced by Germanic.

I hope we can see more and more anthropological papers like this, using traditional linguistics coupled with archaeology and the most recent genetic investigations.

EDIT (4 JUL 2018): Some errors corrected.

Related:

- East Bell Beakers, an in situ admixture of Yamna settlers and GAC-like groups in Hungary

- Consequences of Damgaard et al. 2018 (III): Proto-Finno-Ugric & Proto-Indo-Iranian in the North Caspian region

- Consequences of Damgaard et al. 2018 (I): EHG ancestry in Maykop samples, and the potential Anatolian expansion routes

- Consequences of Damgaard et al. 2018 (II): The late Khvalynsk migration waves with R1b-L23 lineages

- No large-scale steppe migration into Anatolia; early Yamna migrations and MLBA brought LPIE dialects in Asia

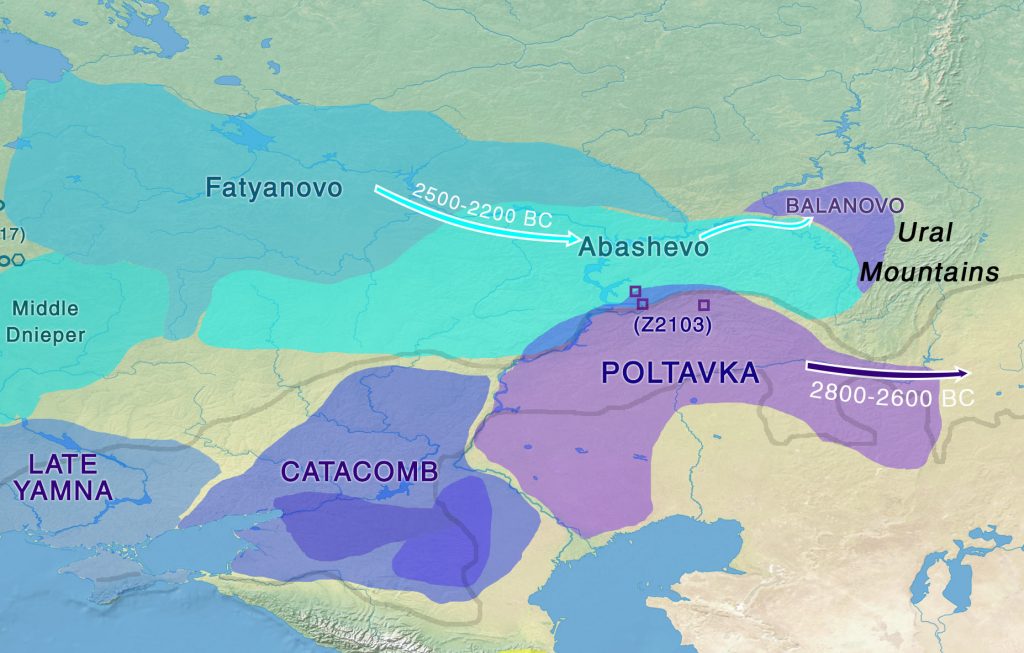

- Early Indo-Iranian formed mainly by R1b-Z2103 and R1a-Z93, Corded Ware out of Late PIE-speaking migrations

- Y-DNA haplogroup R1b-Z2103 in Proto-Indo-Iranians?

- North Pontic steppe Eneolithic cultures, and an alternative Indo-Slavonic model

- The concept of “Outlier” in Human Ancestry (III): Late Neolithic samples from the Baltic region and origins of the Corded Ware culture

- New Ukraine Eneolithic sample from late Sredni Stog, near homeland of the Corded Ware culture

- The renewed ‘Kurgan model’ of Kristian Kristiansen and the Danish school: “The Indo-European Corded Ware Theory”