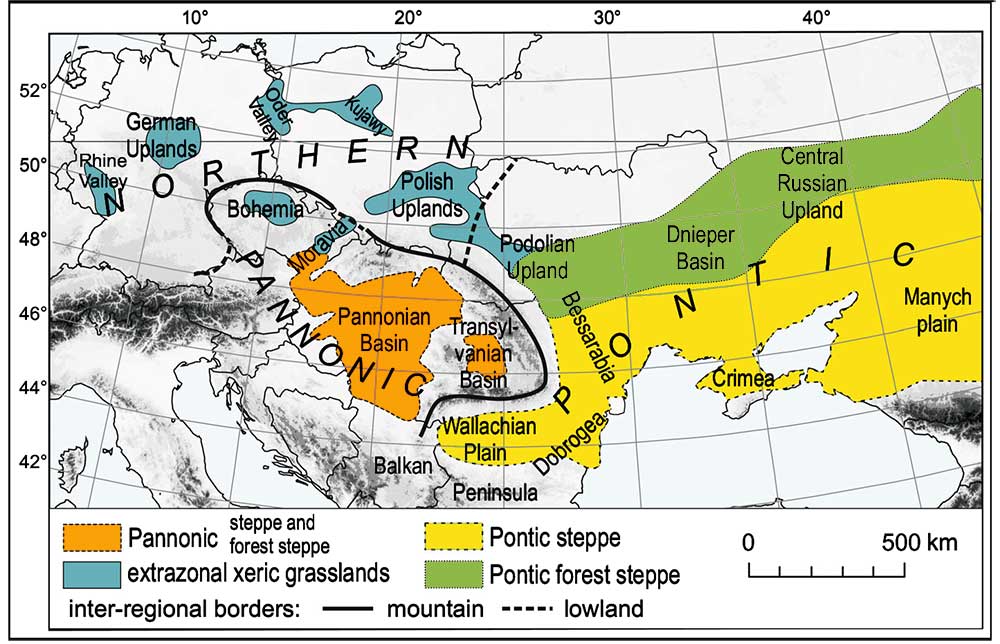

We know that the Caucasus Mountains formed a persistent prehistoric barrier to cultural and population movements. Nevertheless, an even more persistent frontier to population movements in Europe, especially since the Neolithic, is the Pontic-Caspian steppe – forest-steppe ecotone.

Like the Caucasus, this barrier could certainly be crossed, and peoples and cultures could permeate in both directions, but there have been no massive migrations through it. The main connection between both regions (steppe vs. forest-steppe/forest zone) was probably through its eastern part, through the Samara region in the Middle Volga.

The chances of population expansions crossing this natural barrier anywhere else seem quite limited, with a much less porous crossing region in the west, through the Dnieper-Dniester corridor.

A Persistent ecological and cultural frontier

It is very difficult to think about any culture that transgressed this persistent ecological and cultural frontier: many prehistoric and historical steppe pastoralists did appear eventually in the neighbouring forest-steppe areas during their expansions (e.g. Yamna, Scythians, or Turks), as did forest groups who permeated to the south (e.g. Comb Ware, GAC, or Abashevo), but their respective hold in foreign biomes was mostly temporary, because their cultures had to adapt to the new ecological environment. Most if not all groups originally from a different ecological niche eventually disappeared, subjected to renewed demographic pressure from neighbouring steppe or forest populations…

The Samara region in the Middle Volga may be pointed out as the true prehistoric link between forests and steppes (see David Anthony’s remarks), something reflected in its nature as a prehistoric sink in genetics. This strong forest – forest-steppe – steppe connection was seen in the Eurasian technocomplex, during the expansion of hunter-gatherer pottery, in the expansion of Abashevo peoples to the steppes (in one of the most striking cases of population admixture in the area), with Scythians (visible in the intense contacts with Ananyino), and with Turks (Volga Turks).

Before the emergence of pastoralism, the cultural contacts of the Pontic region (i.e. forest-steppes) with the Baltic were intense. In fact, the connection of the north Pontic area with the Baltic through the Dnieper-Dniester corridor and the Podolian-Volhynian region is essential to understand the spread of peoples of post-Maglemosian and post-Swiderian cultures (to the south), hunter-gatherer pottery (to the north), TRB (to the south), Late Trypillian groups (north), GAC (south), or Comb Ware (south) (see here for Eneolithic movements), and finally steppe ancestry and R1a-Z645 with Corded Ware (north). After the complex interaction of TRB, Trypillia, GAC, and CWC during the expansion of late Repin, this traditional long-range connection is lost and only emerges sporadically, such as with the expansion of East Germanic tribes.

A barrier to steppe migrations into northern Europe

One may think that this barrier was more permeable, then, in the past. However, the frontier is between steppe and forest-steppe ecological niches, and this barrier evolved during prehistory due to climate changes. The problem is, before the drought that began ca. 4000 BC and increased until the Yamna expansion, the steppe territory in the north Pontic region was much smaller, merely a strip of coastal land, compared to its greater size ca. 3300 BC and later.

This – apart from the cultural and technological changes associated with nomadic pastoralism – justifies the traditional connection of the north Pontic forest-steppes to the north, broken precisely after the expansion of Khvalynsk, as the north Pontic area became gradually a steppe region. The strips of north Pontic and Azov steppes and Crimea seem to have had stronger connections to the Northern Caucasus and Northern Caspian steppes than with the neighbouring forest-steppe areas during the Upper Palaeolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic.

NOTE. We still don’t know the genetic nature of Mikhailovka or Ezero, steppe-related groups possibly derived from Novodanilovka and Suvorovo close to the Black Sea (which possibly include groups from the Pannonian plains), and how they compare to neighbouring typically forest-steppe cultures of the so-called late Sredni Stog groups, like Dereivka or partly Kvityana.

Despite the Pontic-Caspian steppes and forest-steppes neighbouring each other for ca. 2,000 km, peoples from forested and steppe areas had an obvious advantage in their own regions, most likely due to the specialization of their subsistence economy. While this is visible already in Palaeolithic and Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, the arrival of the Neolithic package in the Pontic-Caspian region incremented the difference between groups, by spreading specialized animal domestication. The appearance of nomadic pastoralism adapted to the steppe, eventually including the use of horses and carts, made the cultural barrier based on the economic know-how even stronger.

Even though groups could still adapt and permeate a different territory (from steppe to forest-steppe/forest and vice-versa), this required an important cultural change, to the extent that it is eventually complicated to distinguish these groups from neighbouring ones (like north-west Pontic Mesolithic or Neolithic groups and their interaction with the steppes, Trypillia-Usatovo, Scythians-Thracians, etc.). In fact, this steppe – forest-steppe barrier is also seen to the east of the Urals, with the distinct expansion of Andronovo and Seima-Turbino/Andronovo-like horizons, which seem to represent completely different ethnolinguistic groups.

As a result of this cultural and genetic barrier, like that formed by the Northern Caucasus:

1) No steppe pastoralist culture (which after the emergence of Khvalynsk means almost invariably horse-riding, chariot-using nomadic herders who could easily pasture their cows in the huge grasslands without direct access to water) has ever been successful in spreading to the north or north-west into northern Europe, until the Mongols. No forest culture has ever been successful in expanding to the steppes, either (except for the infiltration of Abashevo into Sintashta-Potapovka).

2) Corded Ware was not an exception: like hunter-gatherer pottery before it (and like previous population movements of TRB, late Trypillia, GAC, Comb Ware or Lublin-Volhynia settlers) their movements between the north Pontic area and central Europe happened through forest-steppe ecological niches due to their adaptation to them. There is no reason to support a direct connection of CWC with true steppe cultures.

3) The so-called “Steppe ancestry” permeated the steppe – forest-steppe ecotone for hundreds of years during the 5th and early 4th millennium BC, due to the complex interaction of different groups, and probably to the aridization trend that expanded steppe (and probably forest-steppe) to the north. Language, culture, and paternal lineages did not cross that frontier, though.

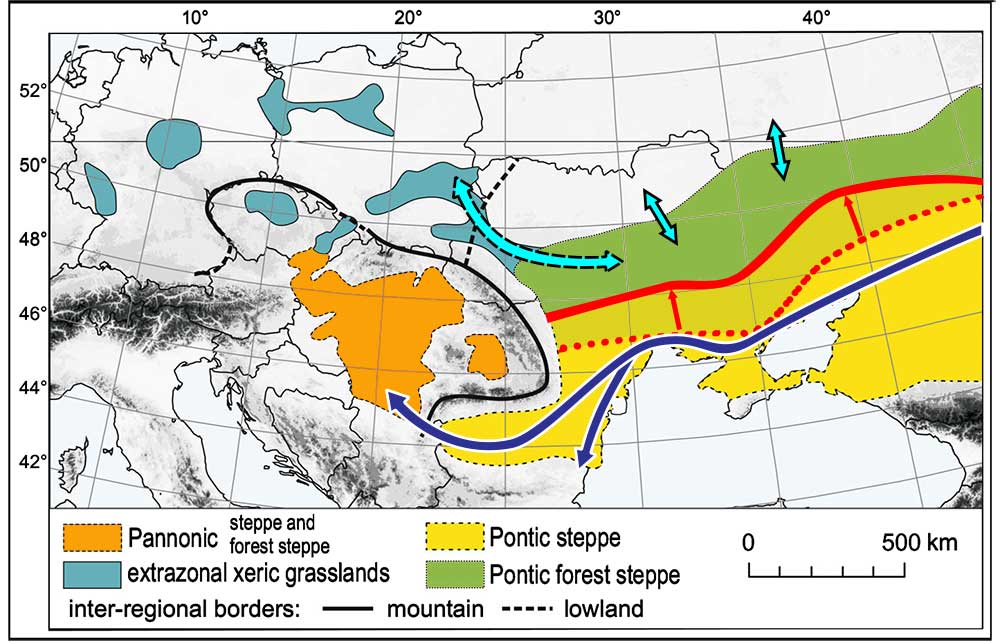

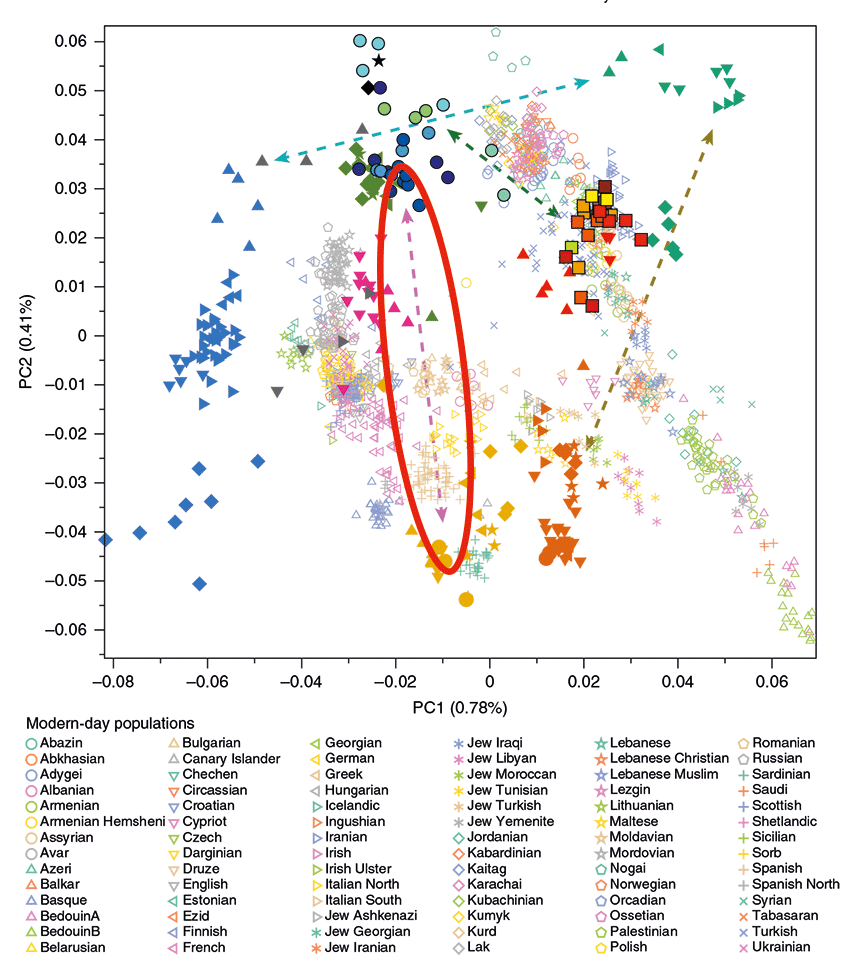

EDIT (4 FEB 2019): Wang et al. is out in Nature Communications. They deleted the Yamna Hungary samples and related analyses, but it’s interesting to see where exactly they think the trajectory of admixture of Yamna with European MN cultures fits best. This path could also be inferred long ago from the steppe connections shown by the Yamna Hungary -> Bell Beaker evolution and by early Balkan samples:

Related

- The uneasy relationship between Archaeology and Ancient Genomics

- Dzudzuana, Sidelkino, and the Caucasus contribution to the Pontic-Caspian steppe

- Steppe and Caucasus Eneolithic: the new keystones of the EHG-CHG-ANE ancestry in steppe groups

- On the origin of haplogroup R1b-L51 in late Repin / early Yamna settlers

- On the origin and spread of haplogroup R1a-Z645 from eastern Europe

- Corded Ware culture origins: The Final Frontier

- Sredni Stog, Proto-Corded Ware, and their “steppe admixture”

- Kurgan origins and expansion with Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka chieftains

- About Scepters, Horses, and War: on Khvalynsk migrants in the Caucasus and the Danube

- The Caucasus a genetic and cultural barrier; Yamna dominated by R1b-M269; Yamna settlers in Hungary cluster with Yamna

- The concept of “Outlier” in Human Ancestry (III): Late Neolithic samples from the Baltic region and origins of the Corded Ware culture

- Consequences of Damgaard et al. 2018 (II): The late Khvalynsk migration waves with R1b-L23 lineages

- On the potential origin of Caucasus hunter-gatherer ancestry in Eneolithic steppe cultures

- North Pontic steppe Eneolithic cultures, and an alternative Indo-Slavonic model

- New Ukraine Eneolithic sample from late Sredni Stog, near homeland of the Corded Ware culture

- The renewed ‘Kurgan model’ of Kristian Kristiansen and the Danish school: “The Indo-European Corded Ware Theory”