Another interesting paper, Life in the fast lane: Settled pastoralism in the Central Eurasian Steppe during the Middle Bronze Age, by Judd et al. (2017).

Abstract (emphasis mine):

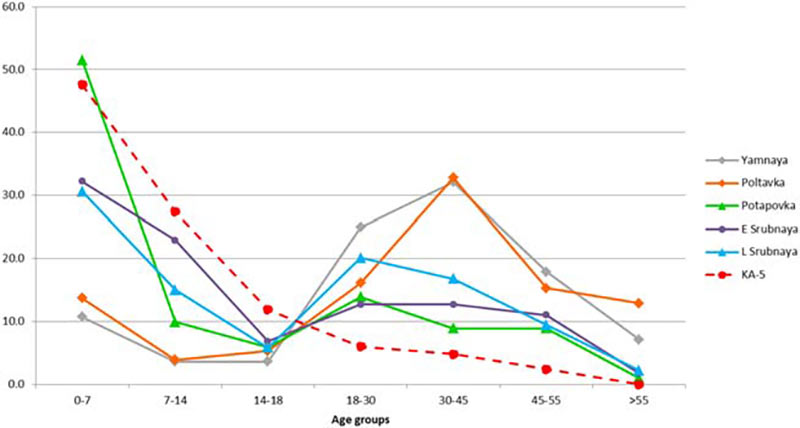

We tested the hypothesis that the purported unstable climate in the South Urals region during the Middle Bronze Age (MBA) resulted in health instability and social stress as evidenced by skeletal response.The skeletal sample (n = 99) derived from Kamennyi Ambar 5 (KA-5), a MBA kurgan cemetery (2040-1730 cal. BCE, 2 sigma) associated with the Sintashta culture. Skeletal stress indicators assessed included cribra orbitalia, porotic hyperostosis, dental enamel hypoplasia, and tibia periosteal new bone growth. Dental disease (caries, abscess, calculus, and periodontitis) and trauma were scored. Results were compared to regional data from the nearby Samara Valley, spanning the Early to Late Bronze Age (EBA, LBA).Lesions were minimal for the KA-5 and MBA-LBA groups except for periodontitis and dental calculus. No unambiguous weapon injuries or injuries associated with violence were observed for the KA-5 group; few injuries occurred at other sites. Subadults (<18 years) formed the majority of each sample. At KA-5, subadults accounted for 75% of the sample with 10% (n = 10) estimated to be 14-18 years of age.Skeletal stress markers and injuries were uncommon among the KA-5 and regional groups, but a MBA-LBA high subadult mortality indicates elevated frailty levels and inability to survive acute illnesses. Following an optimal weaning program, subadults were at risk for physiological insult and many succumbed. Only a small number of individuals attained biological maturity during the MBA, suggesting that a fast life history was an adaptive regional response to a less hospitable and perhaps unstable environment

Interesting excerpt:

The low frequencies of violence-related trauma contrast sharply to the epidemic of skeletal violence observed during the Iron Age (8th-2nd centuries BC) at other regional sites, notably Aymyrlyg (Murphy, 2003). The paucity of weapon-related injuries among the Bronze Age groups may be the outcome of many factors. While weapons and chariots did exist, they could have had multi-functional contexts aside from warfare. Individuals killed in warfare may not be present if bodies were abandoned on battlefields or disposed of where the individual died. Alternatively, warfare may have involved the capture of humans in addition to material resources, such as herds or weapons, leaving no skeletal trace of physical violence (Martin, Harrod, & Fields, 2010; Wilkinson, 1997). Trauma analysis is further complicated by the lack of soft tissue, which is the target for those attempting to kill or immobilize their opponent (Judd, 2008; Judd & Redfern, 2012), and it is possible that violence-related injuries or burns sustained from metallurgy were absent because only the soft tissue was affected. The skeletal evidence for trauma is minimal at KA-5 and its contemporary sites, which may be partially attributed to the less than desirable preservation of the collections. Based on the skeletal material available, internal or external social tensions resulting in altercations are not supported.

The lack of material or skeletal evidence for warfare has encouraged a more optimistic interpretation of Steppe community relations living with environmental instability. Herding camps, such as that at Peschanyi Dol, provided evidence for assorted groups utilizing the site based on the clay sources of ceramic sherds found in the camp’s trash pit (Anthony, Brown, Kuznetsov, & Mochalov, 2016a). Anthony et al. (2016a, 2016b) suggested that herders shifted according to a schedule that permitted several settlements to use prime camp sites. They proposed a cooperative region-wide organization of groups that worked together in three key activities: mining, summer herding, and winter wolf-dog rituals (Anthony et al., 2016a). A similar regional social arrangement may have existed in the KA-5 vicinity and accords with the livestock management models proposed by Stobbe and colleagues (2016).

Using the available sampling, and based on the absence of skeletal stress markers (in combination with the high subadult mortality among Sintashta samples), the study concludes that the available data cannot support the traditional view that MBA was a period of social strife.

Since other Samara Valley samples do not follow a similar trend with Sintashta, a homogeneous, long-term relationship with the environment is suggested for this culture, independent of climatic shift or unpredictability.

We already know that R1a-Z645 subclades, which expanded with the Corded Ware culture, appeared in a Poltavka cemetery rather early, which, coupled with the incomplete replacement that we see in Early Indo-Iranian communities, suggest a gradual expansion of its (mostly R1a-Z93) subclades among Proto-Indo-Iranians.

My limited, speculative proposal of how this lineage replacement took place was based precisely on this traditional description of partially isolated, warring communities:

The process by which this cultural assimilation happened in the Sintashta-Petrovka region, given the presupposed warring nature of their contacts, remains unclear. It is conceivable, in a region of highly fortified settlements, to think about alliances of different groups against each other, akin to the situation found in Bronze Age Europe: a minority of Abashevo chiefs and their families would dominate over certain fortified settlements and wage war against other, neighbouring tribes.

After a certain number of generations, the most successful settlements would have replaced the paternal lineages of the region – with only a slight drift to steppe admixture observed in PCA compared to Corded Ware –, while the majority of the population in these settlements – including females, commoners and slaves – retained the original Poltavka culture. R1b1a1a2a2-Z2103 lineages were mostly replaced in the region by haplogroup R1a1a1b2-Z93, as demonstrated by the later expansion of its subclades with Andronovo and Srubna cultures, and by present-day distribution of R1a1a1b2-Z93 lineages in Eurasia.

Now we see more proof for a likely bottleneck in a more peaceful (or, rather, cooperative) region, as recently described by Anthony. In fact, if you take a look at the sampling of the paper (which is obviously not randomised), Potapovka – coeval with Sintashta, but genetically more similar to the earlier Yamna and Poltavka – follows a less steep demographic distribution than Sintashta, with succeeding Srubna (which shows a marked shift toward the Corded Ware cluster) maintaining a similar demographic pattern…

I guess the answer is probably between both positions, war and environment; the main issue is which one was the most important contributing factor. If we judged the whole picture solely by the samples studied in this paper, the answer would be the environment.

In any case, even though we like to see every single paternal lineage substitution in a territory as necessarily linked with a meaningful migration coupled with ethnolinguistic change, sometimes this is not the case; as, the replacement of R1b-L23 lineages in Proto-Balto-Slavic and Proto-Indo-Iranian communities by R1a-Z645 subclades; the replacement of R1a-Z645 by N1c-L392 subclades in Uralic-speaking territories; or the replacement of native lineages by R1b-L51 subclades among Basques.

Related:

- Early Indo-Iranian formed mainly by R1b-Z2103 and R1a-Z93, Corded Ware out of Late PIE-speaking migrations

- Y-DNA haplogroup R1b-Z2103 in Proto-Indo-Iranians?

- The Aryan migration debate, the Out of India models, and the modern “indigenous Indo-Aryan” sectarianism

- Consequences of O&M 2018 (I): The latest West Yamna “outlier”

- Olalde et al. and Mathieson et al. (Nature 2018): R1b-L23 dominates Bell Beaker and Yamna, R1a-M417 resurges in East-Central Europe during the Bronze Age

- The Indo-European demic diffusion model, and the “R1b – Indo-European” association

- The concept of “Outlier” in Human Ancestry (III): Late Neolithic samples from the Baltic region and origins of the Corded Ware culture

- New Ukraine Eneolithic sample from late Sredni Stog, near homeland of the Corded Ware culture

- Germanic–Balto-Slavic and Satem (‘Indo-Slavonic’) dialect revisionism by amateur geneticists, or why R1a lineages *must* have spoken Proto-Indo-European