New paper (behind paywall) The Production of Thin‐Walled Jointless Gold Beads from the Maykop Culture Megalithic Tomb of the Early Bronze Age at Tsarskaya in the North Caucasus: Results of Analytical and Experimental Research, by Trifonov et al. Archaeometry (2018)

Interesting excerpts (emphasis mine):

In 1898, two megalithic tombs containing graves of a local social elite dated to the Early Bronze Age were discovered by N. I. Veselovsky near the village of Tsarskaya (modern Novosvobodnaya, Republic of Adygeya) (Fig. 1 (a)) (Baye 1900, 43–59; IAC 1901, 33–8; Sagona 2018, 281–97).

Radiocarbon dates place both tombs within the Novosvobodnaya phase of the Maykop culture, between c. 3200 and 2900 BC (Trifonov et al. 2017). Along with the human remains (one adult individual was interred in each dolmen), the tombs yielded rich funerary offerings, including artefacts made of gold, silver and semi-precious stones. (…) This paper presents results of a technical analysis of just one type of artefact, from kurgan 2 at Tsarskaya: thin-walled jointless beads made from gold.

Ever since M. I. Rostovtzeff noted a stylistic similarity between Maykop art and Sumerian art (Rostovtzeff 1920) and M. V. Andreeva described this phenomenon within a broad cultural and chronological context (Andreeva 1977), new archaeological studies have only extended this picture of a vast cultural province that appeared between the Caucasus and the northern fringe of Western Asia (Trifonov 1987). The discovery of the Leyla-Tepe culture (Narimanov 1987) and Maykop-type kurgans in Azerbaijan (Lyonnet et al. 2008) and adjacent Iran (Muscarella 1969, 1971, 2003; Trifonov 2000) has confirmed the spatial and temporal unity of this phenomenon as a precondition for free circulation of cultural patterns and technical innovations across vast areas of the Caucasus and Western Asia. Jewellery made of gemstones and precious metals, primarily gold, was probably one such innovation.

Attempts to demarcate the historical region where the Maykop culture emerged and developed have emphasized the role of Upper Mesopotamia in the development of the Sumerian civilization and the definition of a northern centre of urbanization, independent from the centres of the south (Rothman 2002; Oats et al. 2007). The turn of the fourth millennium BC saw the development of various cultural traditions in south-east Anatolia, north-east Syria and north-west Iran; on the northern fringe, these traditions manifested themselves through the Maykop culture. Perhaps it is no coincidence that the first high-status burials containing gold and gemstone jewellery (including carnelian, turquoise and lapis lazuli) appear in these northern, rather than southern, centres in the first quarter of 4000 BC (e.g., Tepe Gawra, graves 109, 110) (Piasnall 2002). With regard to funeral rites and stylistic characteristics of jewellery pieces, these graves have many parallels with early Maykop burials (Munchaev 1975, 329; Trifonov 1987, 20).

It still remains unclear if the goldsmiths of Upper Mesopotamia mastered the technique of making thin-walled jointless beads. The gold beads from Tepe Gawra are described as spherical or ball-shaped, but their maximum diameter (5–8mm) always exceeds the length of the bore (3–4mm) (Tobler 1950, 89, 199, pl. LV, a). On the whole, these measurements are consistent with the proportions and sizes of some Maykop beads.(…)

It is quite possible that a distinctive technique of making thin-walled jointless beads from gold was a regional technological development of Maykop culture goldsmiths, within a wider tradition of Near East metalwork, as a type of production regulated by ritual beliefs (Gell 1992; Benzel 2013).

These deep-rooted Near East traditions of ritualization of the production and use of jewellery pieces made of gold, silver and gemstones in the Maykop culture, on the one hand, maintained familiar canons of ritual behaviour and, on the other, made perception of sophisticated symbolism of gemstones more difficult for neighbouring cultures with different living standards, levels of social development and value systems to understand. The jewellery traditions of the Maykop culture had no successors in the Caucasus or the adjacent steppes. In the third millennium BC, the goldsmiths of Europe and Asia had to reinvent the technique of making thin-walled jointless gold beads from scratch (Born et al. 2009).

Also interesting is Holocene environmental history and populating of mountainous Dagestan (Eastern Caucasus, Russia), by Ryabogina et al., Quaternary International (2018).

Related excerpts, about the climate of an adjacent region of the Caucasus before, during, and after the Maykop culture:

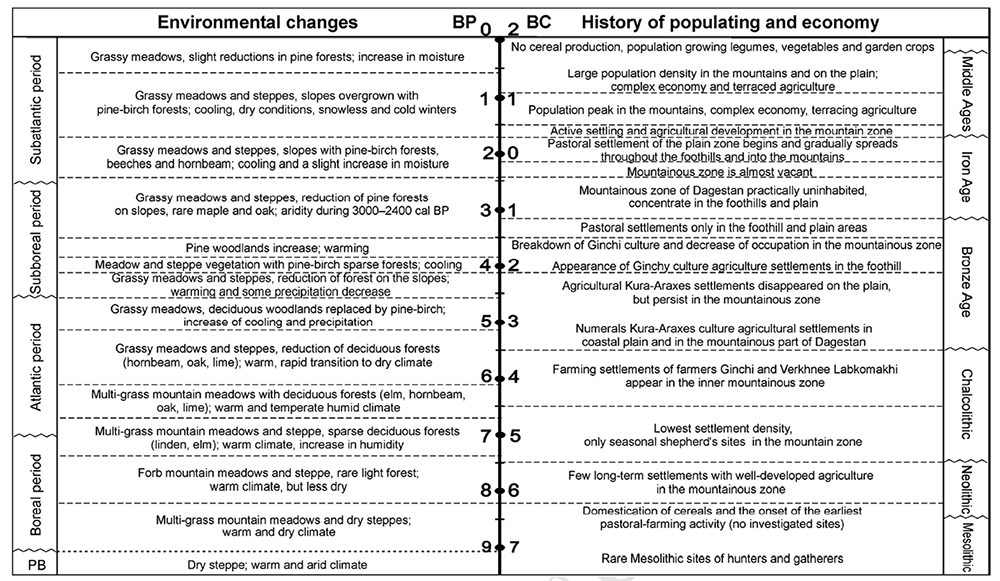

The 7th millennium BC featured a warm and arid climate, so that time corresponds to the steppe landscapes in the final stage of the Mesolithic. It is likely that the formation of a producing economy in the mountainous zone of Dagestan gradually emerged against this background. In the Neolithic period, the area remained almost treeless, as it was still warm and quite dry. However, archaeological data indicates that long-term settlements with well-developed farming spread in the mountainous zone around 6200-5500 BC.

The beginning of increasing humidity and the appearance of deciduous forests corresponds to the early Chalcolithic period of the Eastern Caucasus. It is the most poorly studied period in the history of this region. Covering a time span of 2000 years, this period was the least saturated by archaeological sites. At the start of this period, only the stands of herdsman in the mountain zone are known, dating to the second half of the 6th millennium BC (Gadgiev, 1991). It is still not clear whether the mountains were not settled in such a favorable climatic stage. The uncertainty may be due to the fact that people have chosen other ecological niches, or it could be we simply do not have data due to the insufficient archaeological survey of the territory. It is surprising that the turn to drier climate and the reduction of deciduous forests in the inner mountainous part of Dagestan, the large, long-term settlements like Ginchi emerge with pronounced specialization in agriculture (Fig. 7 panel (2)) (Gadgiev, 1991).

After the dry climate, simultaneously with cooling, the subsequent spread of pine forests coincides with the beginning of expansion of Kura-Araxes culture from the territory of Georgia through Chechnya to the mountainous Dagestan. Debates on the impact of past climate on Kura-Araxes societies in Transcaucasus have a long history (for the comprehensive review see, for example, Connor and Kvavadze, 2014 and references therein). In general, it is clear that after 3000 BC, forest cover in most areas of the Kura-Araxes region in the Transcaucasia reached its maximum extent in the Holocene (Connor and Kvavadze, 2014). However, at the same time lakes in Central Anatolia began to dry out and Caspian Sea levels fell (Roberts et al. 2011; Leroy et al. 2013), and arid conditions were identified in mountainous Dagestan in the 4th millennium. Clearly the regional moisture balance shifted in the Eastern Caucasus only in the late 4th to early 3rd millennium BC (this study). The only available radiocarbon dating of Dagestan confirms that the agricultural settlements of the Early Bronze Age appear not in the middle of the 4th millennium BC, but in the early 3rd millennium BC; that is not earlier than the stage of increasing moistening and the appearance of pine forests.

See also:

- Steppe and Caucasus Eneolithic: the new keystones of the EHG-CHG-ANE ancestry in steppe groups

- The Caucasus a genetic and cultural barrier; Yamna dominated by R1b-M269; Yamna settlers in Hungary cluster with Yamna

- Consequences of Damgaard et al. 2018 (I): EHG ancestry in Maykop samples, and the potential Anatolian expansion routes

- No large-scale steppe migration into Anatolia; early Yamna migrations and MLBA brought LPIE dialects in Asia

- Proto-Indo-European homeland south of the Caucasus?

- On the potential origin of Caucasus hunter-gatherer ancestry in Eneolithic steppe cultures

- Consequences of O&M 2018 (II): The unsolved nature of Suvorovo-Novodanilovka chiefs, and the route of Proto-Anatolian expansion

- North Pontic steppe Eneolithic cultures, and an alternative Indo-Slavonic model