Matrilineal and patrilineal genetic continuity of two iron age individuals from a Pazyryk culture burial, by Tikhonov, Gurkan, Peler, & Dyakonov, Int J Hum Genet (2019).

Relevant excerpts (emphasis mine):

Of particular interest to the current study are the archaeogenetic investigations associated with the exemplary mound 1 from the Ak-Alakha-1 site on the Ukok Plateau in the Altai Republic (Polosmak 1994a; Pilipenko et al. 2015). This typical Pazyryk “frozen grave” was dated around 2268±39 years before present (Bln-4977) (Gersdorff and Parzinger 2000). Initial anthropological findings suggested an undisturbed dual inhumation comprising “a middle-aged European- type man” and “a young European-type woman”, both of whom presumably had a high social status among the Pazyryk elite (Polosmak 1994a). In contrast, recent archaeogenetic investigations revealed somewhat contradicting results since analyses at both the amelogenin gene and Y-chromosome short tandem repeat (Y-STR) loci clearly established that both Scythians were actually males and had paternal and maternal lineages that are typically associated with eastern Eurasians (Pilipenko et al. 2015). Through the use of mitochondrial, autosomal and Y-chromosomal DNA typing systems, it was possible to not only investigate the potential relationships between the two ancient Scythians but also to gather initial phylogenetic and phylogeographic information on their paternal and maternal lineages (Pilipenko et al. 2015).

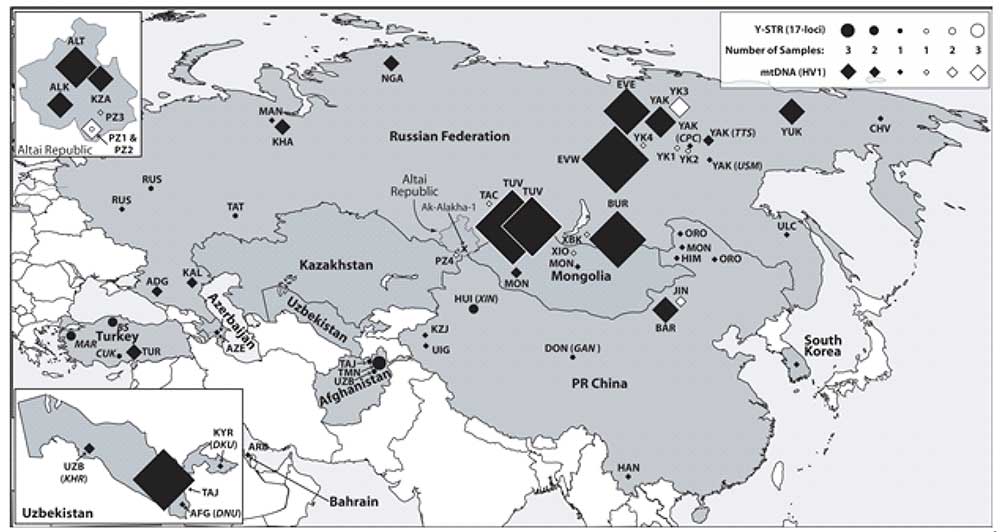

Based on the Y-STR data available, the two Ak-Alakha-1 Scythians had an in silico haplogroup assignment of N, which first appeared in southeastern Asia and then expanded in southern Siberia (Rootsi et al. 2007; Pilipenko et al. 2015).

Current study aims to investigate the geographical distributions of the ancient and contemporary matches and close genetic variants of the maternal and paternal lineages observed in the two Scythians from the exemplary Ak-Alakha-1 kurgan.

In response to aggressive Xiongnu expansion into the Altai region around the 2nd century BCE, some members of the Pazyryk culture may have started moving up North, and eventually reached the Vilyuy River at the beginning of 1st century CE. Notably, there is clear population continuity between the Uralic people such as Khants, Mansis and Nganasans, Paleo-Siberian people such as Yukaghirs and Chuvantsi, and the Pazyryk people even when considering just the two mtDNA and Y-STR haplotypes from the Ak-Alakha-1 mound 1 kurgan (Tables 1a, b, Table 2, Fig. 1). These concepts are also in agreement with the famous Yakut ethnographer Ksenofontov, who suggested that technologies associated with ferrous metallurgy were brought to the Vilyuy Valley at around 1st century CE by the first (proto)Turkic-speaking pioneers (Ksenofontov 1992). Yakut ethnogenesis per se possibly involved two major stages, the first being the proto-Turkic epoch through the arrival of Scytho-Siberian culture originating from Southern Siberia, such as that associated with the Pazyryk culture and the second being the proper Turkic epoch.

Nomadic peoples from the Central Asian steppes are East Iranian speakers whenever they are of haplogroup R1a, but “Uralic-Altaic” speakers whenever they are of haplogroup N. True story.

So they followed a haplogroup ca. 37,000 years old, in a sample dated some 2,300 years ago, whose precise subclade and ancient history is (yet) unknown, compared it to present-day populations, and the result is that they spoke “Uralic-Altaic” because haplogroup N and continuity. Sound familiar? Yep, it’s the kind of reasoning you might be reading right now about Iberian Bell Beakers, about Bell Beakers, or even about Yamna and their relationship to a Vasconic-Caucasian language, based on haplogroup R1b in modern Basques. Another true story.

Anyway, based on the multi-ethnic federations created during this time, and on the ancestral components visible in the different groups (see a post on Karasuk by Chad Rohlfsen), the Pazyryk culture’s language is unknown, and it could be, as a matter of fact (apart from the obvious East Iranian connection):

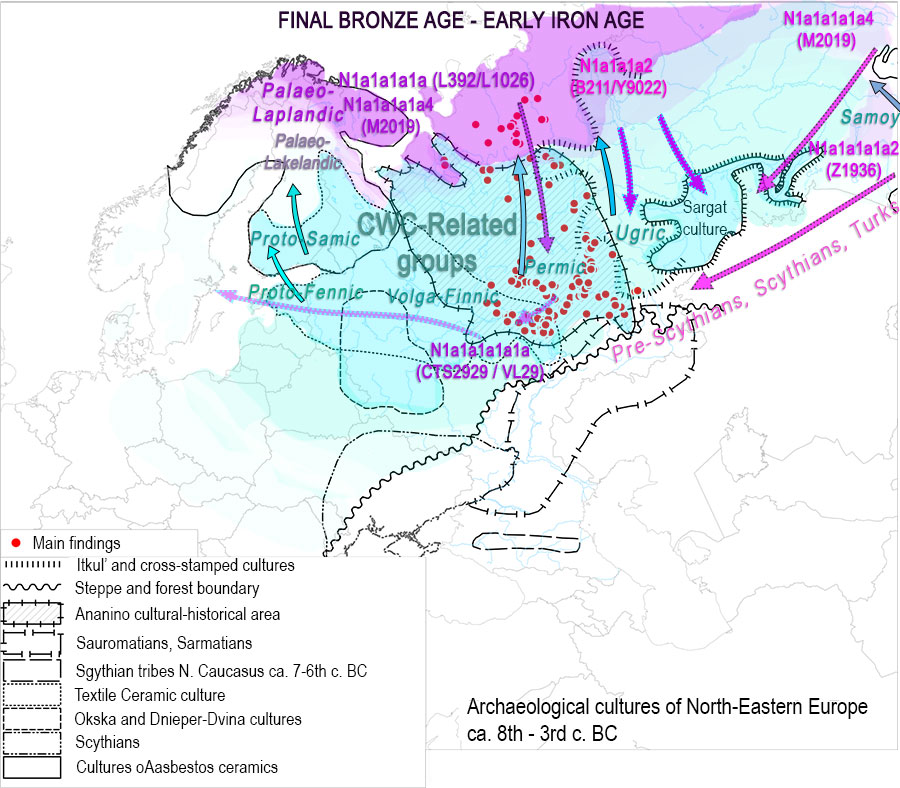

- Uralic: based on the presence of other Uralic-speaking groups nearby in the Siberian forest-steppes, and on their Karasuk-like admixture in common with Eastern Uralians. In fact, we already have a Pazyryk sample of haplogroup R1a-Z2124 from Berel’ in the Altai region (ca. 4th-3rd c. BC) from Unterländer et al. (2017), which may correspond to Eastern Uralic peoples (as the Bronze Age expansion of R1a-Z645 up to the eastern steppes shows). The appearance of haplogroup N in elite individuals would be quite representative of the infiltration process that must have happened among Ugrians and Samoyeds, and among Finno-Permians in the west.

- Turkic: based on the presence of haplogroup N in West Siberian forest and forest-steppe groups – including Botai, which shows Y-DNA hg. R1b-M73 and N – because we really don’t know where Proto-Turkic comes from, and by the Iron Age (even if the connection with Eurasians speaking a Eurasiatic macro-language is correct) it could be associated with any (and possibly many) haplogroups, as the presence of R1a-Z645 lineages among Hunnic-Sarmatian groups show.

We also know that haplogroup N and Siberian ancestry expanded into cultures of Northern Eurasia precisely with the creation of the new social paradigm of chiefdoms and alliances, roughly at the same time as Scythians expanded, with the first sample of haplogroup N in Hungary appearing with Cimmerians.

While the study of modern populations is interesting, the problem I have with the paper is the reasoning of “language of ancient haplogroups based on modern populations”, and especially with the concept of “Uralic-Altaic”, and the highly hypothetic “Proto-Turkic” nomadic steppe pastoralists before “Hunnic Turkic” (which is itself questionable), before the “real Turkic” layer (being the authors apparently Turkic themselves), and the supposed “continuity” of Eastern Uralic and Turkic groups in Asia since the Out of Africa migration. The combination of all of this in the same text is just disturbing.

If you look at it from the bright side, at least these samples were not of haplogroup R1a-Z280, or we would be talking about great Slavonic Scythians showing continuity from Russia with love, as the paper threatened to do in its introduction…

If you are enjoying the comeback of this retro 2000s comedy in 2019 (based on the classic nativist “R1a=IE”, “R1b=Basque”, and “N=Uralic” combo) it’s because you – like me – are putting yourself in this guy’s shoes every time a new episode of funny self-destruction appears:

Related

- Minimal gene flow from western pastoralists in the Bronze Age eastern steppes

- Ancient nomadic tribes of the Mongolian steppe dominated by a single paternal lineage

- Y-DNA haplogroups of Tuvinian tribes show little effect of the Mongol expansion

- Corded Ware—Uralic (II): Finno-Permic and the expansion of N-L392/Siberian ancestry

- Corded Ware—Uralic (III): “Siberian ancestry” and Ugric-Samoyedic expansions

- Corded Ware—Uralic (IV): Haplogroups R1a and N in Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic

- Haplogroup R1a and CWC ancestry predominate in Fennic, Ugric, and Samoyedic groups

- The Iron Age expansion of Southern Siberian groups and ancestry with Scythians

- Evolution of Steppe, Neolithic, and Siberian ancestry in Eurasia (ISBA 8, 19th Sep)

- Mitogenomes from Avar nomadic elite show Inner Asian origin

- Oldest N1c1a1a-L392 samples and Siberian ancestry in Bronze Age Fennoscandia

- Genetic prehistory of the Baltic Sea region and Y-DNA: Corded Ware and R1a-Z645, Bronze Age and N1c

- More evidence on the recent arrival of haplogroup N and gradual replacement of R1a lineages in North-Eastern Europe