New paper (behind paywall) A case-study in historical sociolinguistics beyond Europe: Reconstructing patterns of multilingualism in a linguistic community in Siberia, by Khanina and Meyerhoff, Journal of Historical Sociolinguistics (2018) 4(2).

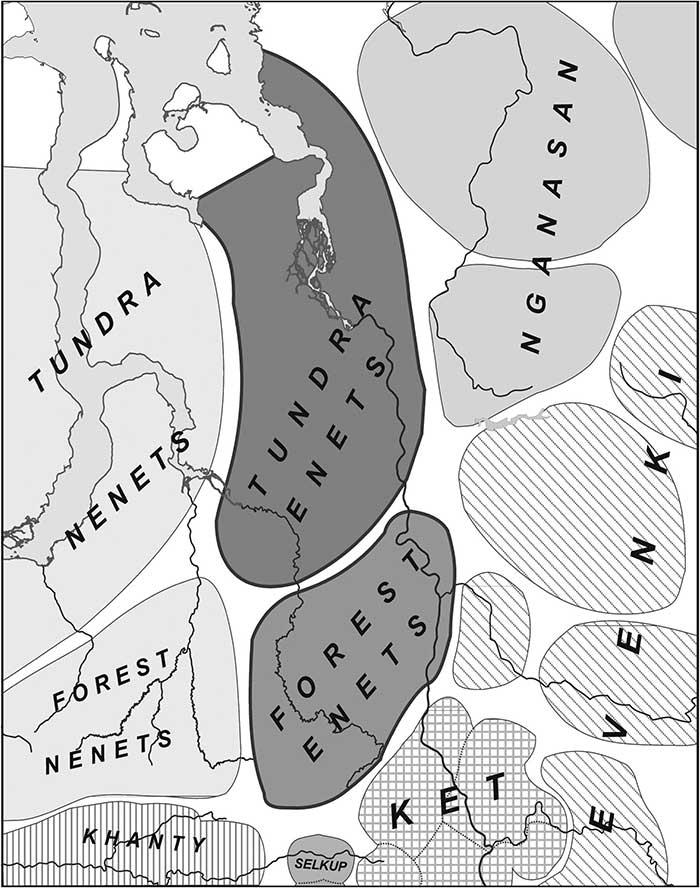

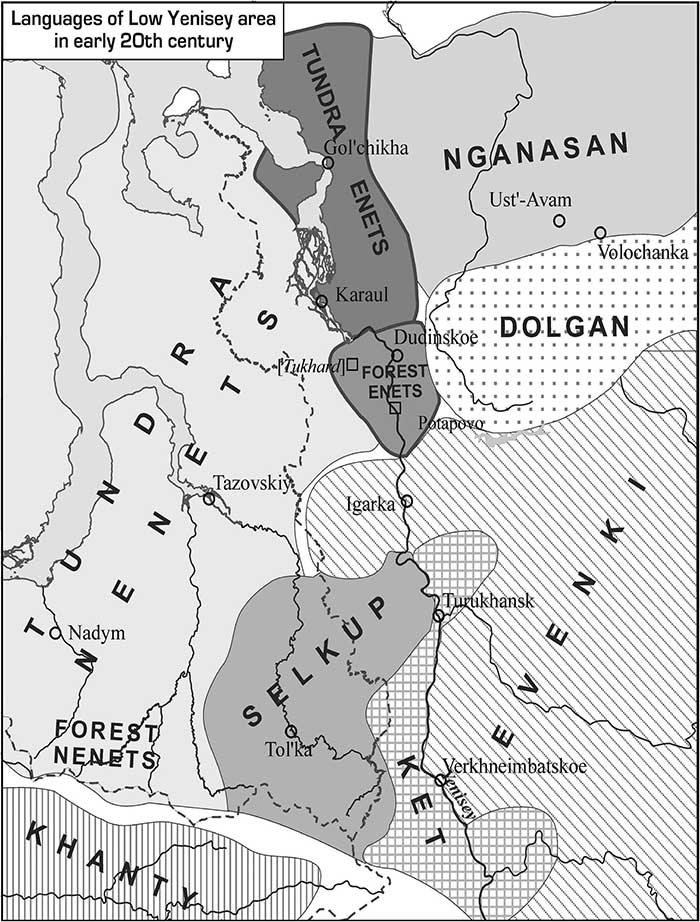

The Nganasans have been eastern neighbours of the Enets for at least several centuries, or even longer, as indicated in Figures 2 and 3.10 They often dwelled on the same grounds and had common households with the Enets. Nganasans and Enets could intermarry (Dolgikh 1962a), while the Nganasans did not marry representatives of any other ethnic groups. As a result, it was not unusual for Enets and Nganasans to live in the same tent and/or to have common relatives. Such close contact must clearly have favoured acquisition of Nganasan by Enets children and of Enets by Nganasan children from an early age.

The Nenets have been close neighbours of all the Enets groups more recently (Figures 2 and 3). In the seventeenth century, there were only warlike contacts between the Nenets and the Enets, while in the eighteenth century the Nenets started to live on the traditional Enets lands, on the western bank of the Yenisey river, with more peaceful interactions reported. (…) Since then the same situation of intermarriages and common households has been attested for these western Enets neighbours as with the Nganasans (Dolgikh 1962a), and this has also created conditions favouring early acquisition of both languages by children.

As for the Evenkis and the Selkups, the Enets had regular contact with these peoples (Figures 2 and 3), though they were not their close neighbours: in fact, geographically, the Selkups were not neighbours at all by the end of the nineteenth century. The Evenkis had always been direct south-eastern neighbours (…) Contacts with Selkups could be trade based, or they could simply be occasional encounters on adjacent lands. (…) [With Evenkis] some sporadic contacts were similar in nature to those with the Selkups, however many other contacts were war-like. Traditionally, the Enets considered the Evenkis to have a martial spirit, and the Evenkis were known as being accustomed to stealing Enets women. A number of stories in Dolgikh (1961) concern Evenkis stealing Enets women and Enets men going to Evenki lands to find and return them. It is clear, therefore, that if Evenki or Selkup were acquired by the Enets, this happened later in life, and this acquisition required particular conditions for it, i. e. it was not readily acquired through regular or harmonious contact (as with Nganasan).

In a pattern similar to the situation with Nganasan, in the second half of the twentieth century most Enets elders could speak Nenets (Vasil’jev 1963; Eugen Helimski p.c., the lead author’s fieldwork experience).

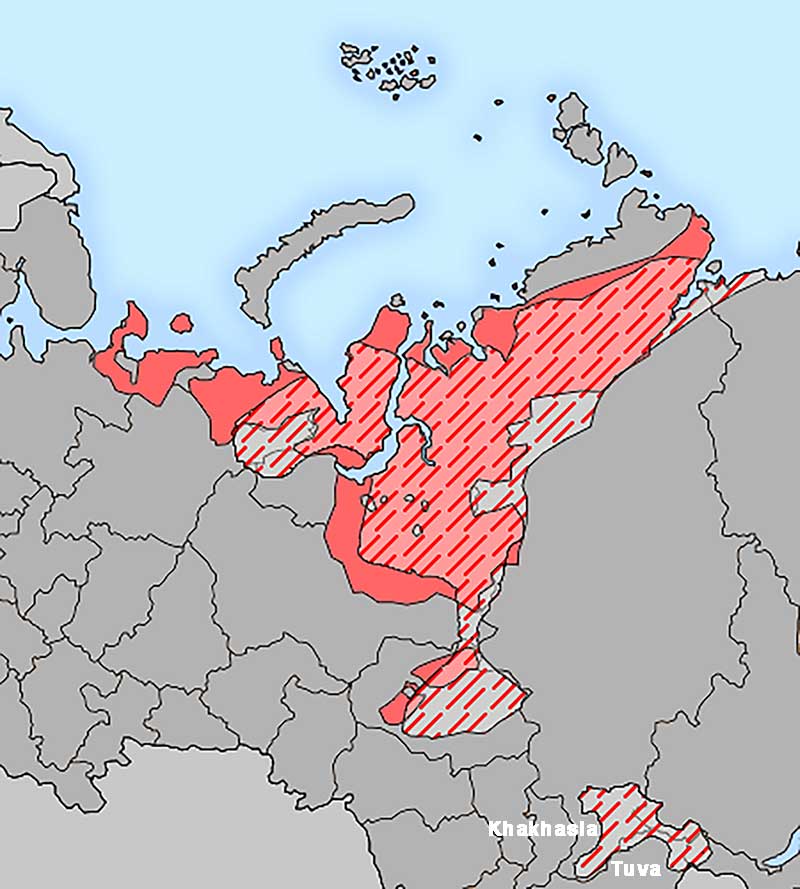

Bruk (1961).

At the start of the period studied, in the 1850s, the Enets linguistic community could be characterized as multilingual in the following five languages: Enets, Nganasan, Nenets, Evenki, and Russian (Figure 4). The number of Enets individuals who were able to converse in each of the other four languages differed and generally was a property of the individuals who had regular social contact with speakers of the other four languages. (…) Note that in all cases of interethnic communication there could well be a lack of perfect proficiency in a language for which the multilingualism is ascribed to the Enets community or Enets individuals: as Braunmüller and Ferraresi (2003: 3) put it: “Nobody would ever have expected to know other languages ‘perfectly’ (whatever that may mean in detail). This expectation seems to be a quite modern idea when discussing issues of bilingualism or multilingualism in general”.

The complex interactions of Siberian populations during the 17th-19th centuries offer a reasonably good picture of the life in the centuries before these accounts, when Samoyedic peoples migrated northwards, and Palaeo-Siberian and Tungusic populations were gradually assimilated into their Uralic culture and language, through intermarriage and close contacts among naturally nomadic populations.

You can read more about the origin of Nganasans – and other modern Samoyedic-speaking peoples – as Palaeo-Siberian populations (hence probably speaking Palaeo-Siberian languages more or less related to each other) who adopted Samoyedic languages in Wikipedia, which offers a summary of Boris Dolgikh’s On the Origin of the Nganasans (1962). Dolgikh is one of the main sources of information for these Siberian groups, as is reflected in this paper, too.

Why some geneticists are using Nganasans – in fact the latest Palaeo-Siberians to learn Samoyedic, already during historic times – as a model for the expansion of Uralic? I have never understood that. Among the many cases of circular reasoning based on modern populations that have been created since the start of population genomics, the use of Nganasans as a model of ‘true Uralians’ is probably the most clearly frontally opposed to what was well known in anthropology before geneticists started this new field.

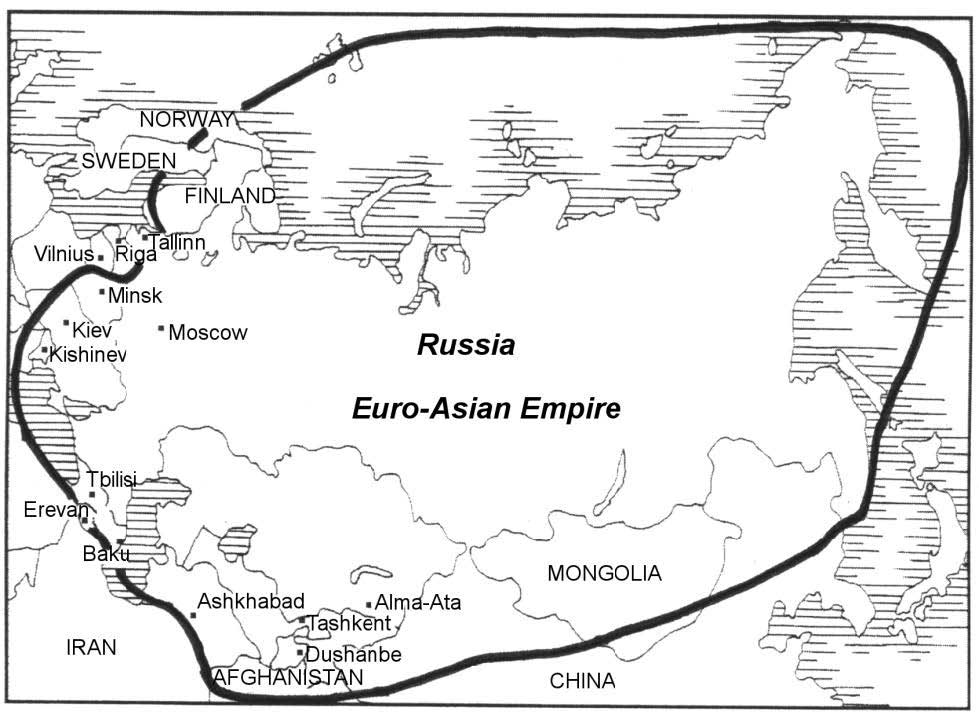

If Kallio is right, most “eastern homeland” proposals are due to the interest of Russian nationalism, which is sadly quite likely to be influencing genetic research, too. It’s like letting Hindu nationalists influence publications on steppe-related migrations. As David Reich puts it in his book:

The tensest twenty-four hours of my scientific career came in October 2008, when my collaborator Nick Patterson and I traveled to Hyderabad to discuss these initial results with Singh and Thangaraj.

Our meeting on October 28 was challenging. Singh and Thangaraj seemed to be threatening to nix the whole project. Prior to the meeting, we had shown them a summary of our findings, which were that Indians today descend from a mixture of two highly divergent ancestral populations, one being “West Eurasians.” Singh and Thangaraj objected to this formulation because, they argued, it implied that West Eurasian people migrated en masse into India. They correctly pointed out that our data provided no direct evidence for this conclusion. They even reasoned that there could have been a migration in the other direction, of Indians to the Near East and Europe. (…) They also implied that the suggestion of a migration from West Eurasia would be politically explosive. They did not explicitly say this, but it had obvious overtones of the idea that migration from outside India had a transformative effect on the subcontinent.

If you add the nation-building myths in Eastern Europe (like the Russian Euro-Asian movements) to the now prevalent Indo-European—CWC idea, and a Siberian ancestry peaking in the Arctic, with little demographic or political relevance of modern Uralic-speaking peoples, you have clearly an explosive sociopolitical mix (based on a mythical Pan-Eurasian Indo-Slavonic) in the making…

Related

- Y-DNA haplogroups of Tuvinian tribes show little effect of the Mongol expansion

- Iron Age bottleneck of the Proto-Fennic population in Estonia

- Corded Ware—Uralic (II): Finno-Permic and the expansion of N-L392/Siberian ancestry

- Corded Ware—Uralic (I): Differences and similarities with Yamna

- Haplogroup R1a and CWC ancestry predominate in Fennic, Ugric, and Samoyedic groups

- On the origin and spread of haplogroup R1a-Z645 from eastern Europe

- Oldest N1c1a1a-L392 samples and Siberian ancestry in Bronze Age Fennoscandia

- Consequences of Damgaard et al. 2018 (III): Proto-Finno-Ugric & Proto-Indo-Iranian in the North Caspian region