New paper (behind paywall) The female ancestor’s tale: Long‐term matrilineal continuity in a nonisolated region of Tuscany, by Leonardi et al. Am J Phys Anthr (2018).

EDIT (10 SEP 2018): The main author has shared an open access link to read the PDF.

Interesting excerpts:

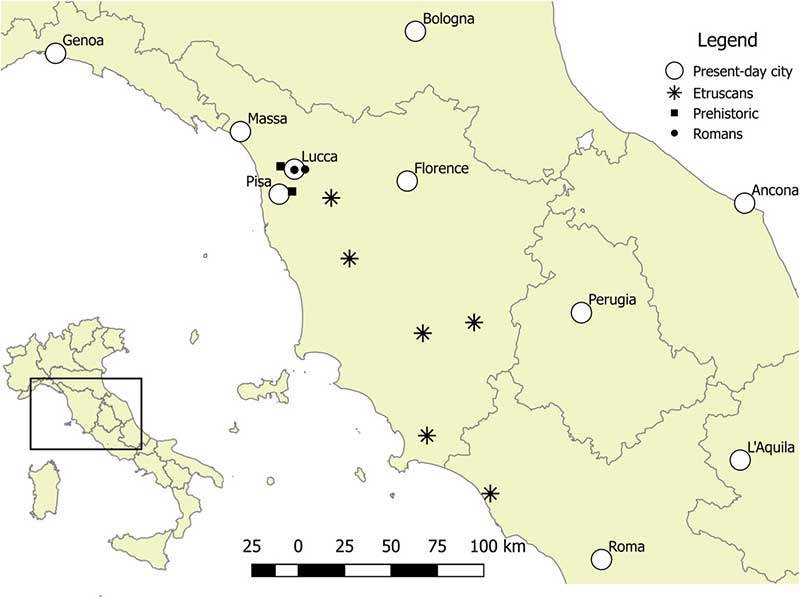

Here we analyze North-western Tuscany, a region that was a corridor of exchanges between Central Italy and the Western Mediterranean coast.

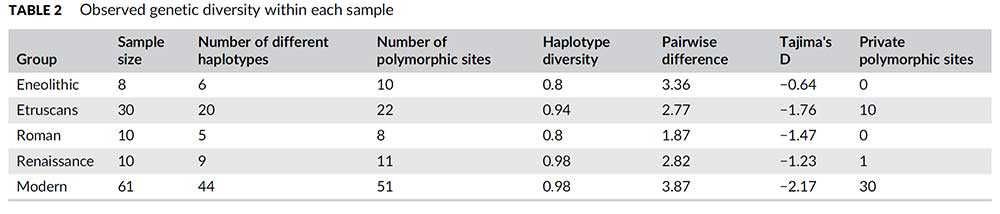

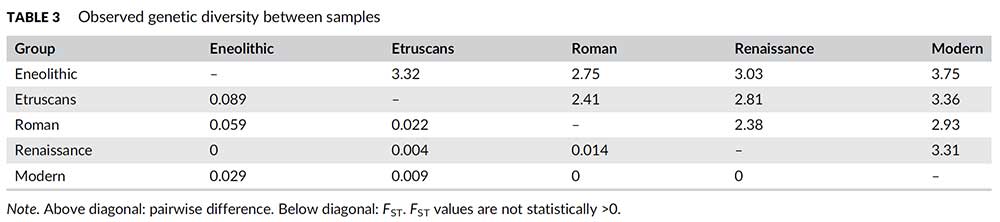

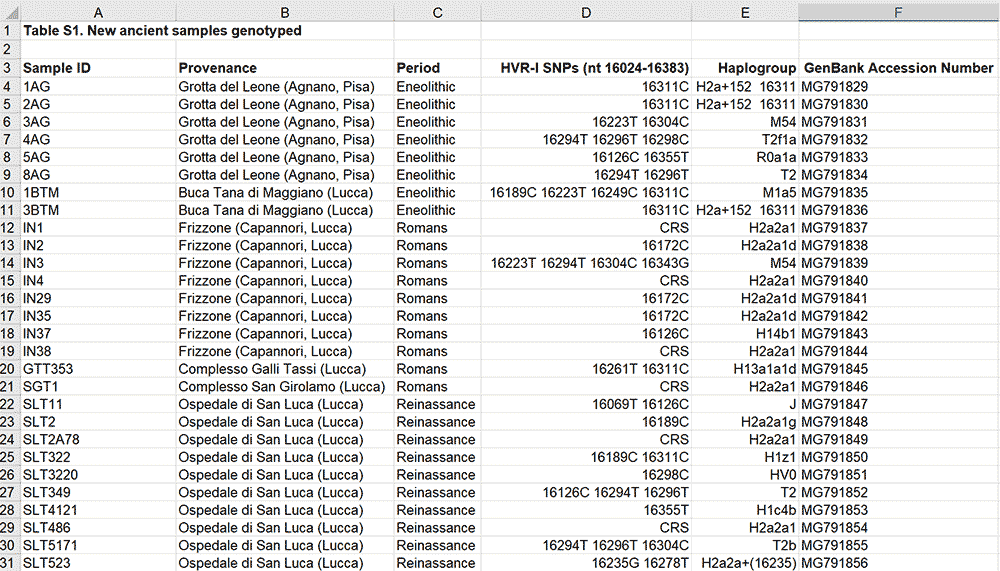

We newly obtained mitochondrial HVRI sequences from 28 individuals, and after gathering published data, we collected genetic information for 119 individuals from the region. Those span five periods during the last 5,000 years: Prehistory, Etruscan age, Roman age, Renaissance, and Present-day. We used serial coalescent simulations in an approximate Bayesian computation framework to test for continuity between the mentioned groups.

In all cases, a simple model of a long-term genealogical continuity proved to fit the data better, and sometimes much better, than the alternative hypothesis of discontinuity.

The low number of samples analyzed requires some caution in the interpretation. Because we did not test for gene flow, it is at this stage impossible to reject it, but our results suggest at least significant levels of genealogical continuity. Moreover, as it has not been possible to obtain more precise information on the age of the Eneolithic samples, they were grouped together considering the average archaeological period of interest, which may cause a bias in the analyses. (…)

(…) clearly, our samples show high levels of continuity when considering the whole Tuscan region as a genetic reservoir during the Iron Age.

The posterior distributions of the parameters confirm a high degree of genetic isolation in the sampled population, with very small values for the female effective population sizes across time. Such values, in particular the Neolithic ones, are in accord with the estimates obtained in similar studies, both in Tuscany (Ghirotto et al., 2013) and in France (Rivollat et al., 2017).

Taken at their face value, our results do not show any major shift in the composition of the maternal ancestry of the population, across 50 centuries. This does not mean that no demographic process of relevance has affected the population, and indeed the higher diversity accumulating in time is the likely consequence of immigrating people, enriching the mitochondrial gene pool.

(…) the population of the current Lucca province appears to have retained very ancient mitochondrial features, despite occupying a geographical corridor between the Ligurian and the Tyrrhenian coast, and despite not showing the persistence of unique cultural traits through the centuries.

Another possibility is that that the different populations passing through the area (Etruscans, Romans, and Lombards) had a consistent social and/or sex bias. An example of similar patterns has been observed several times. Between the Late Neolithic and the Early Bronze Age, female exogamy in patrilocal society has been observed in Southern Germany (Knipper et al., 2017); during the Bronze Age the migrations toward Europe from the steppes appears to have consisted prevalently of males (Goldberg, Günther, Rosenberg, & Jakobsson, 2017); and in more recent periods in the Canary Islands, the female ancestry maintains a significant amount of autochthonous lineages, while the male ancestry was strongly influenced by the European colonization (Fregel et al., 2009, b).

It is well known that military invasions may not have a significant genetic impact upon the invaded population (Schiffels et al., 2016; Sokal, Oden, Walker, Di Giovanni, & Thomson, 1996;Weale,Weiss, Jager, Bradman, & Thomas, 2002), especially at the mitochondrial level, because of the limited size of a sustainable army, and of the fact that armies are generally composed mostly or only of males. Even if a substantial share of invaders decided to remain and settle the region, this form of gene flow would affect mostly or only the paternal lineages, rather than the maternal ones. We can also hypothesize the immigration of a number of people (e.g., Romans, Lombards) that may have acted as ruler of the region, remaining socially (and so genetically) separated by the local population, and leaving few (if any) traces in the gene pools of the local population.

We expect to see that certain migrations since the Iron Age – like the Celtic and Roman ones – were somehow different from previous ones, where, at least since the Neolithic, male-dominated expansions were the rule.

If, however, male-biased expansions are also seen during the Iron Age – probably driven by particular subclades then – , this would certainly justify the continuity of admixture in certain regions in spite of these population expansions, and thus the importance of Y-DNA to track more recent language changes.

One of the most interesting details of the upcoming paper of Italic peoples will be the Y-DNA (and admixture) of Etruscans compared to other neighbouring peoples, given the known conflicting theories regarding their recent vs. older origin in the East before the historical record.

Related

- Y-DNA relevant in the postgenomic era, mtDNA study of Iron Age Italic population, and reconstructing the genetic history of Italians

- On Latin, Turkic, and Celtic – likely stories of mixed societies and little genetic impact

- Pre-Roman and Roman mitogenomes from Southern Italy

- Ancient Phoenician mtDNA from Sardinia, Lebanon reflects settlement, genetic diversity, and female mobility

- Y-chromosome mixture in the modern Corsican population shows different migration layers

- Haplogroup J spread in the Mediterranean due to Phoenician and Greek colonizations

- Haplogroup is not language, but R1b-L23 expansion was associated with Proto-Indo-Europeans