Preprint The genetic legacy of continental scale admixture in Indian Austroasiatic speakers, by Tätte et al. bioRxiv (2018).

Interesting excerpts:

Studies analysing mtDNA and Y chromosome markers have revealed a sex-specific admixture pattern of admixture of Southeast and South Asian ancestry components for Munda speakers. While close to 100% of mtDNA lineages present in Mundas match those in other Indian populations, around 65% of their paternal genetic heritage is more closely related to Southeast Asian than South Asian variation. Such a contrasting distribution of maternal and paternal lineages among the Munda speakers is a classic example of ‘father tongue hypothesis’. However, the temporality of this expansion is contentious. Based on Y-STR data the coalescent time of Indian O2a-M95 haplogroup was estimated to be >10 KYA. Recently, the reconstructed phylogeny of 8.8 Mb region of Y chromosome data showed that Indian O2a-M95 lineages coalesce within a clade nested within East/Southeast Asian within the last ~5-7 KYA. This date estimate sets the upper boundary for the main episode of gene flow of Y chromosomes from Southeast Asia to India.

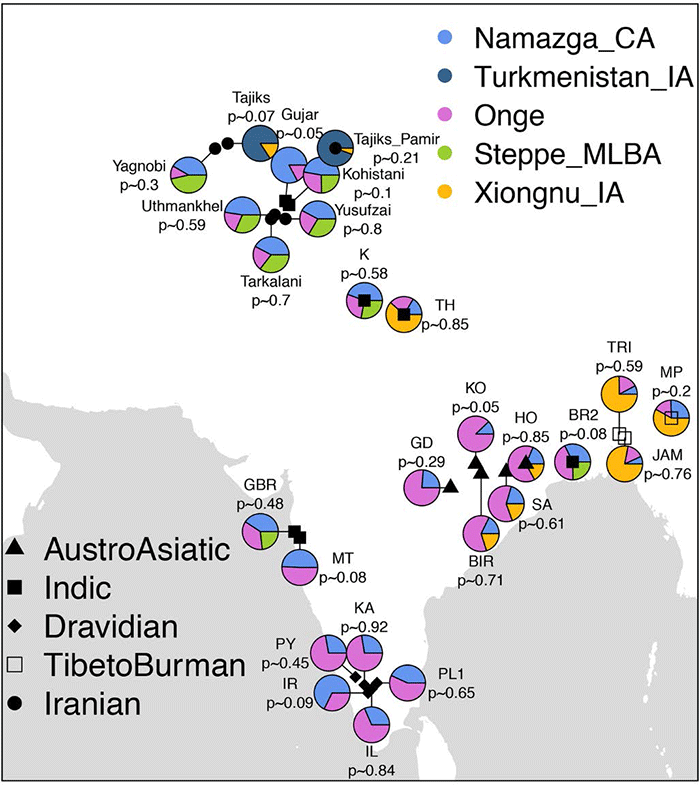

Admixture proportions suggest a novel scenario

Regardless of which West Asian population we used, we found that Munda speakers can be described on average as a mixture of ~19% Southeast Asian, 15% West Asian and 66% Onge (South Asian) components. Alternatively, the West and South Asian components of Munda could be modelled using a single South Asian population (Paniya), accounting on average to 77% of the Munda genome. When rescaling the West and South Asian (Onge) components to 1 to explore the Munda genetic composition prior to the introduction of the Southeast Asian component, we note that the West Asian component is lower (~19%) in Munda compared to Paniya (27%) (Supplementary Table S4: *Average_Lao=0). Consistently with qpGraph analyses in Narasimhan et al. (2018), this may point to an initial admixture of a Southeast Asian substrate with a South Asian substrate free of any West Asian component, followed by the encounter of the resulting admixed population with a Paniya-like population. Such a scenario would imply an inverse relationship between the Southeast and West Asian relative proportions in Munda or, in other words, the increase of Southeast Asian component should cause a greater reduction of the West Asian compared to the reduction in the South Asian component in Munda.

Dating the admixture event

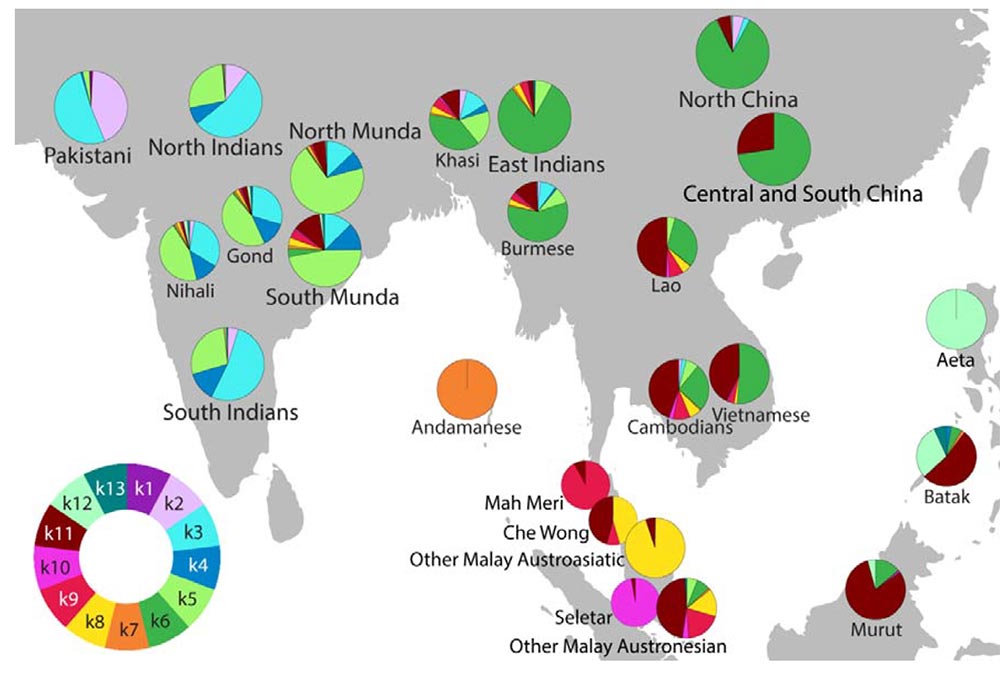

In this study, we have replicated a result previously reported in Chaubey et al. (2011)7 that the Mundas lack one ancestral component (k2) that is characteristic to Indian Indo-European and Dravidian speaking populations. If this component came to India through one of the Indo-Aryan migrations then it would be fair to presume that the Munda admixture happened before this component reached India or at least before it spread all over the country. However, the admixture time computed here, falls in the exact same timeframe as the ANI-ASI mixture has been estimated to have happened in India through which the k2 component probably spread. Therefore, we propose that if the Munda admixture happened at the same time, it is possible for it to have happened in the eastern part of the country, east of Bangladesh, and later when populations from East Asia moved to the area, the Mundas migrated towards central India. Such a scenario, which may be further clarified by ancient DNA analyses, seems to be further supported by the fact that Mundas harbor a smaller fraction of West Asian ancestry compared to contemporary Paniya (Supplementary Table S4) and cannot therefore be seen as a simple admixture product of Southern Indian populations with incoming Southeast Asian ancestries.

Linguistics and genome-wide data

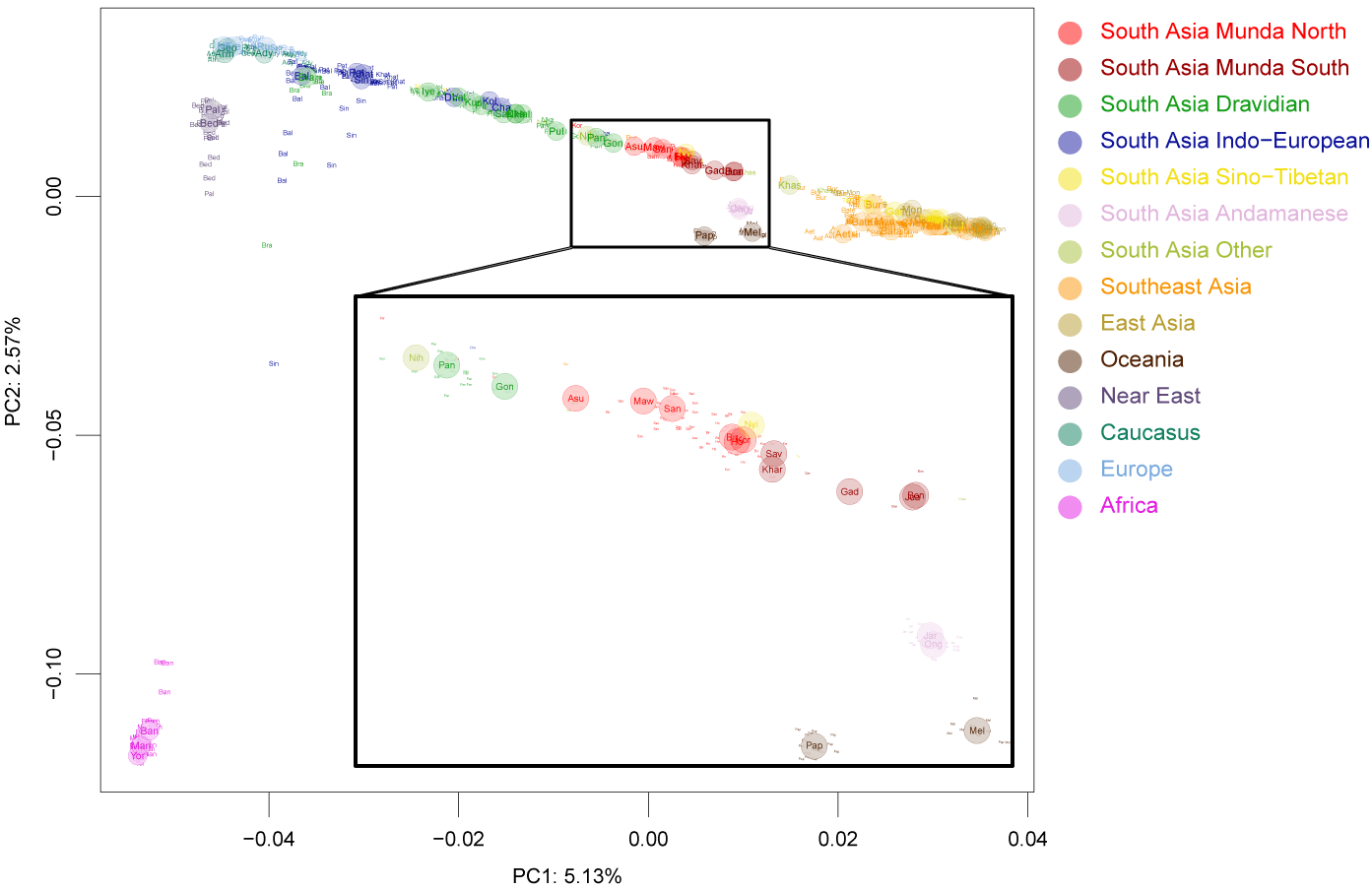

(…) by and large, the linguistic classification justifies itself but Kharia and Juang do not fit in this simplification perfectly.

Once again, with the current level of detail in genetic studies, there is often no clear dialectal division possible for certain groups without fine-scale population studies, and the help from linguistics and archaeology.

Featured image from open access paper by Chaubey et al. (2011).

Related

- No large-scale steppe migration into Anatolia; early Yamna migrations and MLBA brought LPIE dialects in Asia

- Early Indo-Iranian formed mainly by R1b-Z2103 and R1a-Z93, Corded Ware out of Late PIE-speaking migrations

- South-East Asia samples include shared ancestry with Jōmon

- Model for the spread of Transeurasian (Macro-Altaic) communities with farming

- Genomics reveals four prehistoric migration waves into South-East Asia

- Population turnover in Remote Oceania shortly after initial settlement

- Language continuity despite population replacement in Remote Oceania

- Genomic history of South-East Asia: eastern Polynesians, Peninsular Malaysia and North Borneo

- Islands across the Indonesian archipelago show complex patterns of admixture

- Two more studies on the genetic history of East Asia: Han Chinese and Thailand

- Reconstructing the demographic history of the Himalayan and adjoining populations

- Ancient Di-Qiang people show early links with Han Chinese