New paper Biparental Inheritance of Mitochondrial DNA in Humans, by Luo et al. PNAS (2018).

Interesting excerpts (emphasis mine):

Abstract

Although there has been considerable debate about whether paternal mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) transmission may coexist with maternal transmission of mtDNA, it is generally believed that mitochondria and mtDNA are exclusively maternally inherited in humans. Here, we identified three unrelated multigeneration families with a high level of mtDNA heteroplasmy (ranging from 24 to 76%) in a total of 17 individuals. Heteroplasmy of mtDNA was independently examined by high-depth whole mtDNA sequencing analysis in our research laboratory and in two Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments and College of American Pathologists-accredited laboratories using multiple approaches. A comprehensive exploration of mtDNA segregation in these families shows biparental mtDNA transmission with an autosomal dominantlike inheritance mode. Our results suggest that, although the central dogma of maternal inheritance of mtDNA remains valid, there are some exceptional cases where paternal mtDNA could be passed to the offspring. Elucidating the molecular mechanism for this unusual mode of inheritance will provide new insights into how mtDNA is passed on from parent tooffspring and may even lead to the development of new avenues for the therapeutic treatment for pathogenic mtDNA transmission.

An example

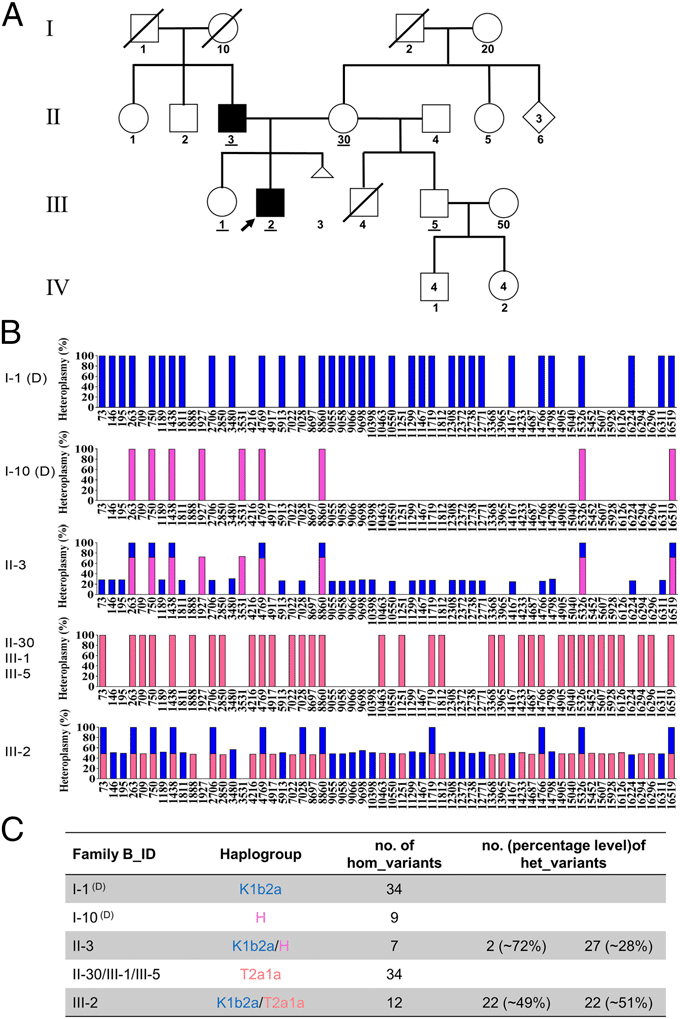

Compared with Family A, a strikingly similar mtDNA transmission pattern was demonstrated in Families B and C. Taking Family B for illustration, II-3 having 29 heteroplasmic and seven homoplasmic variants should have inherited mtDNA from both his father (I-1, haplogroup of K1b2a) and his mother (I-10, haplogroup of H), who were supposed to possess 34 and nine homoplasmic variants, respectively. II-3 further transmitted his mtDNA that he inherited from I-1 to his son (III-2), who also inherited all of his mother’s mtDNA (II-30, carrying 34 variants and a haplogroup of T2a1a). However, III-2’s sister (III-1) and half-brother (III-5) only inherited the maternal mtDNA. Fresh blood sampling and repeated mtDNA sequencing in a second independent laboratory were also performed to rule out the possibility of sample mix-up for III-2 (III-2, column F-G and H-I). Additionally, these samples were further verified using Pacific Bio single molecular sequencing (see Materials and Methods) and by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of Family A, and these results were fully consistent with the previous sequencing.

A Resurgence of the Paternal Transmission Hypothesis

The results presented in this paper make a robust case for paternal transmission of mtDNA. Here, we report biparental mtDNA inheritance (either directly or indirectly) in 17 members in three multigeneration families. Thirteen of these individuals were identified directly by sequencing of the mitochondrial genome, whereas four could be inferred based on preexisting maternal heteroplasmy caused by biparental inheritance in the previous generation.

To further confirm these remarkable results and to exclude the possibility of sample mix-up and/or contamination, the whole mtDNA sequencing procedure was repeated independently in at least two different laboratories by different laboratory technicians with newly obtained blood samples. All results were reproducible, indicating no artifacts or contamination exist. More importantly, the multiple mtDNA variants that were paternally transmitted differ in both number and position among each of these three families as well as the related haplogroup (R0a1 in Family A, K1b2a in Family B, and K2b1a1a in Family C, respectively), providing two distinct forms of evidence supporting transmission of the paternal mtDNA.

Therefore, we have unequivocally demonstrated the existence of biparental mtDNA inheritance as evidenced by the high number and level of mtDNA heteroplasmy in these three unrelated multigeneration families. Most interestingly, the mixed haplogroups in these samples are very reminiscent of the mixed haplogroups found in the 20 studies that were dismissed by Bandelt et al. as due to contamination or sample mix-up. One is forced to wonder how many other instances of individuals with biparental mtDNA inheritance have been dismissed as technical errors, and whether Schwartz and Vissing’s original discovery has really been given the proper follow-up that it deserves. We suspect that these results will initiate a broader reassessment of the topic.

We propose that the paternal mtDNA transmission in these families should be accompanied by segregation of a mutation in one nuclear gene involved in paternal mitochondrial elimination and that there is a high probability that the gene in question operates through one of the pathways identified above.

If I have to be honest, I was stuck with the paternal transmission hypothesis which we were taught in class long ago. I didn’t know it was controversial or dismissed, I just thought it was really exceptional, and I never thought about learning more on the subject.

This paper proves it may be more complicated than that, especially for population genomics purposes, because biparental mtDNA transmission with autosomal dominant-like inheritance puts a serious barrier to a general, simplistic interpretation of mtDNA.

I don’t think it is a blow to all interpretations based on mtDNA, though, because the traditional interpretation should often work statistically. However, one has to be always very careful when saying “if it’s mtDNA from region X, it’s about female exogamy”, especially when samples are from neighbouring regions and similar periods.

The term “uniparental marker” for mtDNA is obviously misleading and shouldn’t be used, and many research papers and interpretations taking mtDNA as strictly uniparental should be taken with a pinch of salt.

Related

- Mitogenomes show likely origin of elevated steppe ancestry in neighbouring Corded Ware groups

- Mitogenomes show Longobard migration was socially stratified and included females

- Mitogenomes from Avar nomadic elite show Inner Asian origin

- mtDNA suggest original East Germanic population linked to Jutland Iron Age and Bell Beaker

- Post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck explained by cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal clans

- Corded Ware—Uralic (IV): Hg R1a and N in Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic expansions

- Polygyny as a potential reason for Y-DNA bottlenecks among agropastoralists

- Reconstruction of Y-DNA phylogeny helps also reconstruct Tibeto-Burman expansion

- David Reich on social inequality and Yamna expansion with few Y-DNA subclades

- Y-DNA relevant in the postgenomic era, mtDNA study of Iron Age Italic population, and reconstructing the genetic history of Italians