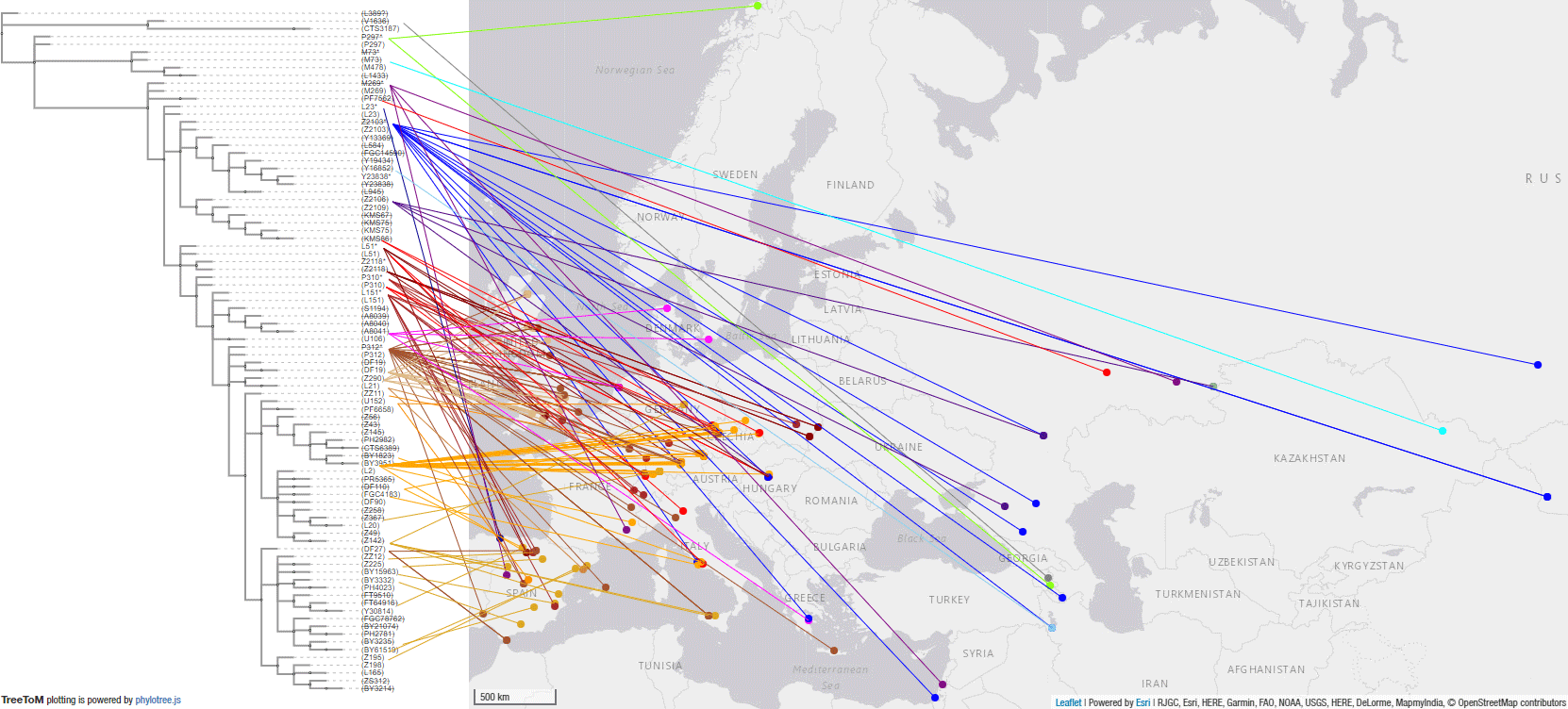

In the recent Linderholm et al. (2020), I preferred to interpret the finding of R1b-P310* among late niche (catacomb) grave groups of Lesser Poland as derived from Late PIE – Late Uralic contacts, through a much earlier intrusion of late Repin/early Yamnaya chieftains among Late Trypillians.

This is one of the few aspects of the books where I tried to offer my own contribution to the field, by combining the Indo-Uralic concept (which supports a distinct evolution of laryngeals for PIE and PU) with a modified, ‘layered’ use of Koivulehto’s controversial and irregular PIE laryngeal borrowing as PU *š.

Admittedly, though, there is yet no evidence of both communities having admixed ca. 1,000 years prior to the emergence of catacomb graves. The alternative interpretation, of later migration waves from the Pontic steppes, has been recently supported by the main archaeologists of the area: A Final Eneolithic Research Inspirations: Subcarpathia Borderlands Between Eastern and Western Europe by Aleksander Kośko and Piotr Włodarczak, Pontic-Baltic Studies (2018) 23(1):259-291. Below are interesting excerpts (emphasis mine, the authors’ emphasis is underlined).

Specificity of Lesser Poland/Subcarpathian forms

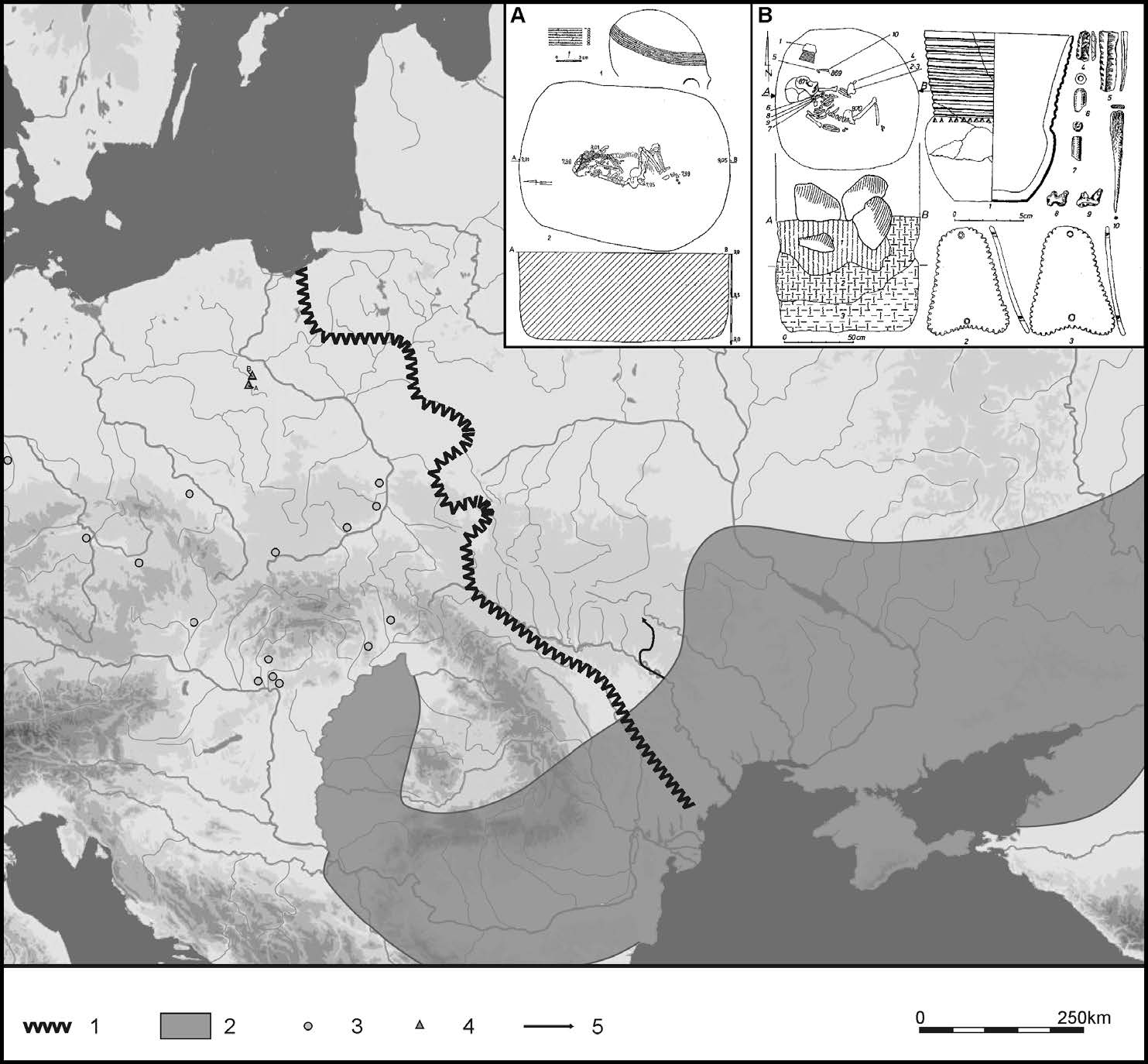

Located in the early third millennium BC, the first step brought about two main new concepts: a barrow (early CWC phase) and a chamber tomb, including its specific form, i.e. catacomb grave (in the case of Złota culture rituals). Dating roughly from the mid-third millennium BC, the second step saw the dissemination of a new niche grave type as well as a custom, whereby some male burials were honoured with rich grave goods, including weapons or a wide array of tools. A source of genetic inspirations for all these traits is usually located east of Lesser Poland, with a specific focus on the northern Black Sea circle of steppe and forest-steppe cultures, i.e. Yamnaya culture (YC) and Catacomb culture (CC).

A. Late Trypillia – Early CWC

(…) Altogether, the CWC funeral ritual should be seen as a separate model that crystallized in Central Europe. The ritual, however, displays clear connections to the northern Black Sea zone, which so far are best visible in the material recovered from lowlands [Kośko 2014; Kośko et al. 2017].

The concept which sees the topogenesis of the central European ritual in the east, or in the steppe, incorporates the view that the horizon of crystallised specific traits of the ritual dating from the older CWC phase (horizon A = CWC-A) was preceded by the infiltration of the northern Black Sea barrow ideology most likely linked to migrations of Late Eneolithic (‘pre-Yamnaya’) ‘barrow communities’, or what is referred to as pre-Corded Ware horizon (CWC-X) [Kośko 2000]. The horizon has been identified based on observations of the expansive nature of pre-Yamnaya and early Yamnaya barrow trends traceable, starting from the late fourth millennium BC in both the Danube-Tisza migration zone [Heyd 2011] and Podolia [Włodarczak 2017b].

At present, the number of barrow graves in Lesser Poland, which are linked to the ‘pre-Corded Ware’ phase, is small. Among indirect indications capable of suggesting an imminent change in this picture, there is information about the presence in the Lviv area of settlements attributable to the Late Tripolye culture/Gordineşti group (site of Vinniki-Zhupan dating from ca. 3300-3100 BC) [Rybicka 2017: 33-40 and latest verbal information] identified with one of the carriers of Eneolithic barrow structures [Ivanova et al. 2015; Włodarczak 2017b]. Discovered before World War II at Zavyshen (Zawisznia), Ukrainian part of Sokal Ridge, a grave containing vessels of the Gordineşti group is yet another indication [Antoniewicz 1925].

B. Black Sea funeral belief reception

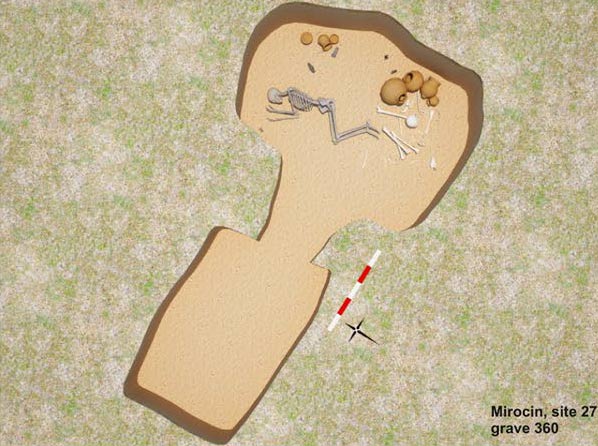

Presented in this volume of Baltic-Pontic Studies, spectacular discoveries from the Rzeszów Foothills (Szczytna) and Lower San Valley, showing cultural connections between Lesser Poland and the northern Black Sea region, were made at niche-grave cemeteries dating from the younger CWC phase, usually referred to as ‘phase of local groups’ – ca. 2600/2500-2300 BC. They are, therefore, linked to the second stage of ‘steppe’ influences specified herein above. Lately, these relations were primarily highlighted in studies addressing the genesis of CWC niche graves in Lesser Poland [Włodarczak 2008: 563-569; 2014b: 21-27]. The standardized nature of a grave structure was noted and described for the Kraków-Sandomierz zone in the first place [Włodarczak 2006: 53-57]. Newly discovered graves on Sokal Ridge [Machnik et al. 2009], Lublin Upland [Jarosz 2016] and in the Carpathian region [first overview: Machnik 2011] point to niches having been a prevailing funeral structure type across Lesser Poland.

Notwithstanding the older genesis of these structures (see structures of the Złota culture), there are indications that allow us to see niche graves of the younger CWC phase as manifestations of a new wave of eastern influences. As it appears from most recent chronometric determinations [Goslar et al. 2015], in the forest-steppe zone of the Northwest Black Sea Coast, these developments followed the younger phase of the YC barrow cemeteries and probably marked the beginning of the prevalence of the CC ritual. Given these findings, construction similarities between catacomb graves of the younger CWC phase and those of the classic CC (including but not limited to the Donetsk or Ingul types) are essential. These similarities make more credible the eastern genesis (ca. 2600-2500 BC) of the Lesser Poland variant of the funeral ritual: all the more so as the grave structure and general burial concept can also be synchronized with the emergence of both specific principles governing depositions of goods, and artefacts that point to their eastern origin.

In qualitative terms, the rich grave goods accompanying CWC male burials in Lesser Poland do not find any close parallels in any other region of central or northern Europe. Their specific nature consists in the presence of archery equipment (several to 30 arrowheads), an extensive set of tools made of bone, antler, copper or stone (including flint), as well as deposits of semi-processed flint. No similar assemblage is known that would come from YC graves. Closer similarities can be found in CC assemblages, including specifically those dating from the 2nd half of the third millennium BC. This is because CC assemblages contain artefacts that suggestively point to craft specialization of the deceased. Clear correspondence can be seen between the assemblages from Lesser Poland and those from the Middle Dnieper culture (…)

Black Sea topogenetic contexts

a. As far as imported raw materials are concerned, circulation of objects made of Volhynia flint, which was used in production of core tools, various types of knife inserts and arrowheads, comes to the fore. Volhynia flint gained a dominant position on the eastern outskirts of Lesser Poland (Sokal Ridge, Roztocze) as well as in the eastern part of Subcarpathia (including but not limited to the Rzeszów Foothills and Lower San Valley). Findings from these areas point to sustainable relationships between CWC communities in Lesser Poland and their Volhynia counterparts, consisting in frequent trips to obtain flint.

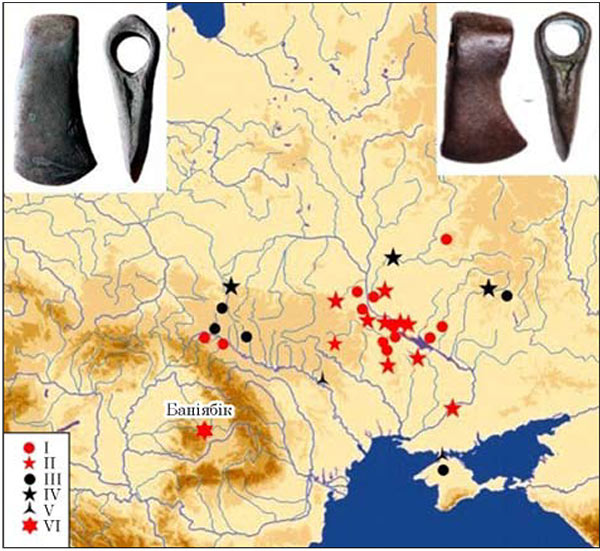

b. The CWC niche graves in Lesser Poland contain items that either demonstrate a clear stylistic change versus the previous period, or constitute a new category of artefacts. Most of the artefacts can be associated with cultural trends resulting from relations between Lesser Poland and the northern Black Sea zone. (…) The battle-axes share some similarities with their contemporary counterparts from the northern Black Sea zone, including specifically CC battle-axes [Włodarczak 2014b: 33-34]. Stylistic inspirations from that circle are particularly clear for sickle-shaped or ‘Ingul’ battle-axes [Klochko, Kośko 2009: 283-287; Libera, Sobieraj 2016: 433-434].

c. At present, it remains an open issue as to whether CWC communities in Lesser Poland were using copper from ‘eastern’ deposits in Volhynia or Podolia [Klochko et al. 2000; 2003; Klochko, Kośko 2013]. The likelihood of this is supported by stylistic affinities among metal objects from south-eastern Poland, northern Black Sea zone and territories occupied by the MDC.

Chronometric landscape of Black Sea funeral belief systems

When summed up, all chronometric data from south-eastern Poland give us a terminus post quem of ca. 2600 BC (most probably: ca. 2550 BC) for the emergence of new communities in Lesser Poland that brought a modified concept of the funeral ritual. The thesis about the presence of newcomers from territories east of Lesser Poland seems to be confirmed also by results of stable strontium isotope analysis performed for materials from the site at Święte [Belka et al. 2018]. Being powerful manifestation of eastern cultural influences, the new funeral ritual was being phased out starting from ca. 2400 BC, with the abandonment of the niche-grave concept, which was replaced with the Bell Beaker/early Mierzanowice trend.

Recapitulation

There is abundant evidence from 2550-2400 BC that confirms reception of Black Sea ‘funeral ideologies’ identified with the late YC and CC, by local CWC communities. It is appropriate to suggest that the ceremonial centres at Szczytna and Święte on the San give evidence of a syncretic cultural construct (=assemblages belonging to the Szczytna – Święte type), which is highly ambiguous in terms of its autogenesis and perhaps found its broader continuation in CWC communities penetrating the upper Dniester [Belka et al. 2018].

A ‘Subcarpathian annex’ to the Final Eneolithic vision of cultural syntheses in the biocultural border zone between eastern and western Europe offers a number of new clues, ones the present paper has tried to capture, occasionally outlining desirable directions for future research.

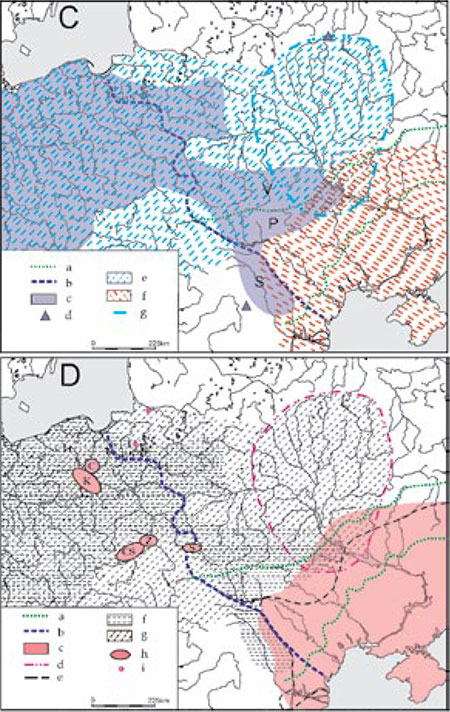

A. 6th and 5th mill. BC. Foll. Kadrow, Zakościelna 2000; Larina, Okhrimenko 2007; Kośko/Szmyt 2009. Key:

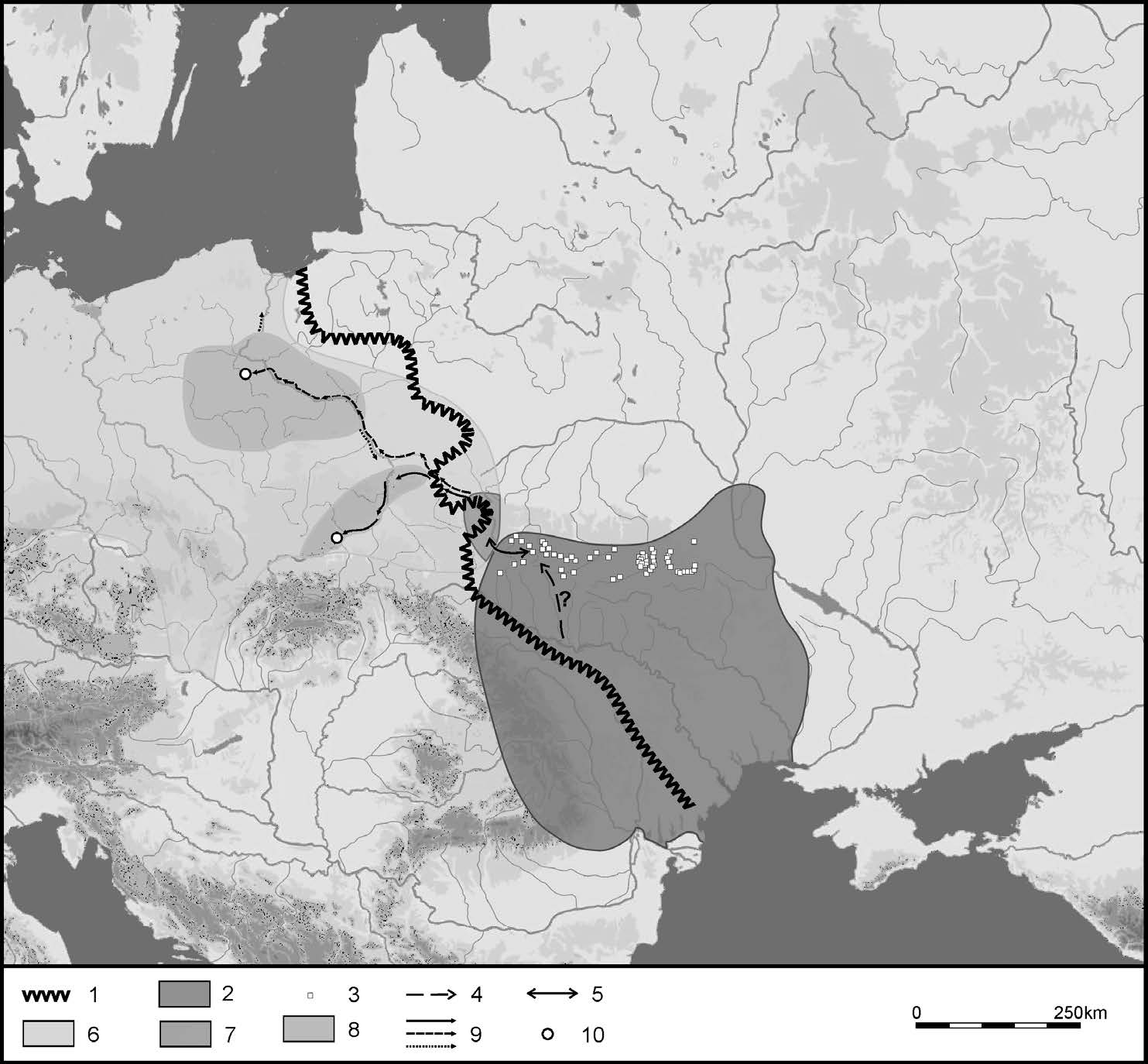

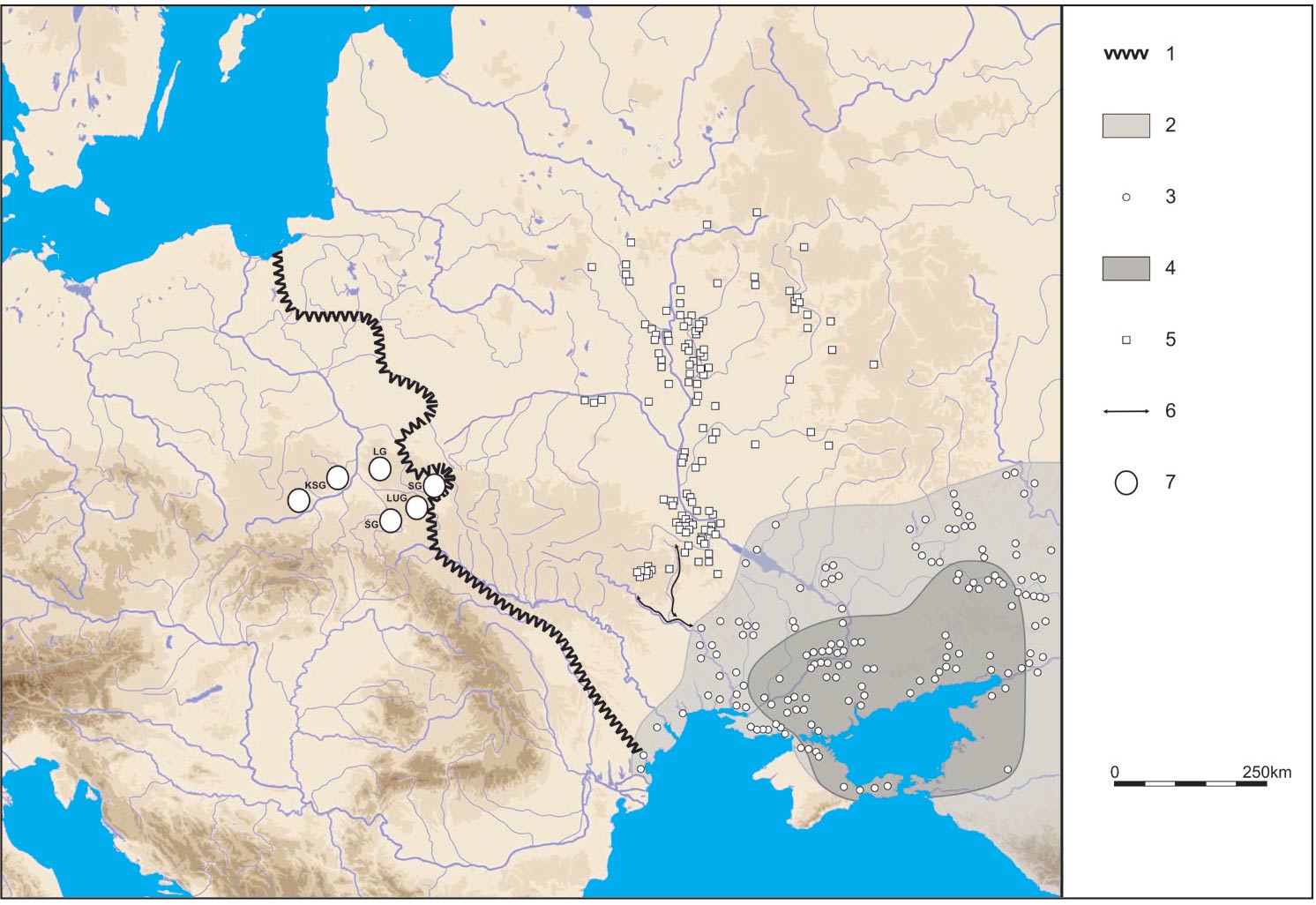

C. 3rd mill. BC. Foll. Szmyt 1999a; Kośko, Szmyt 2009; Szmyt 2013a. Key: a – borders of east European ecological zones; b – Western Bug-Dniester limes; c – range of GAC settlement (eastern group: V – Volhynian subgroup; P – Podolian subgroup; S – Moldavian subgroup); d – isolated sites of GAC; e – range of CWC circle; f – range of Yamnaya culture; g – range of Middle Dnieper culture.

D. Pontic impact in the 3rd mill. BC. Foll. Włodarczak 2006b; Kośko, Szmyt 2009; Machnik 2009; Szmyt 2013a. Key: a – borders of east European ecological zones; b – Western Bug-Dniester limes; c – range of Yamnaya culture; d – range of Middle Dnieper culture; e – range of Catacomb culture; f – range of GAC; g – range of CWC circle; h – areas of reception of Pontic patterns (ZC = Złota culture; CS = Cracow-Sandomierz CWC group; SG = Sokal group; K = Kujawy; C – Chełmno land); i – finds of Pontic origin on the Baltic.

Other evidence

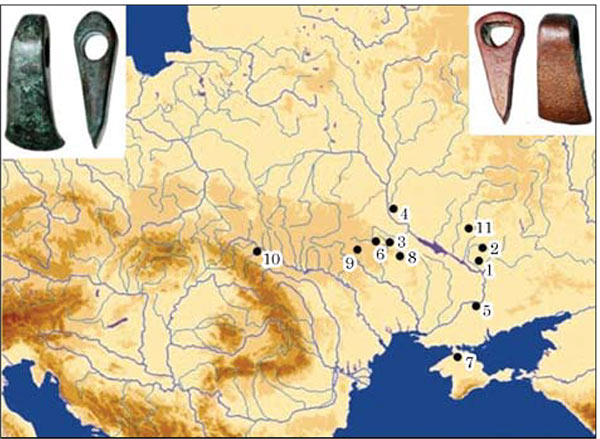

Battle-Axes and their types

Developed Early Bronze Age metallurgy is clearly associated with Steppe societies, and particularly with Yamnaya and derived cultures like Bell Beakers and the Ingul group of the Catacomb culture, but it was also continued among eastern Corded Ware groups in close contact with the steppe, like Middle Dnieper and especially Abashevo. There is a small discussion in this paper which doesn’t really begin to capture the whole discussion of axe types and their origins.

There are two alternative theories about the origin of Steppe-related ‘Banyabik’ axes. In both cases, Yamnaya (and Yamnaya-derived groups) helped spread initially this technique East and West. Like everything related to Final Eneolithic steppe movements, including Yamnaya and Corded Ware differences and similarities, the debate is unlikely to have an ending any time soon:

1) The traditional “Maykop” theory, presented originally by Chernych, Kornievsky or Nechytailo, and currently supported e.g. by Dergachev (see Dergachev 2018). In their view, the so-called Maykop-Novosvobodnaya-Banyabik type axes had an origin in the Caucasus and Trans-Volga, and later expanded to the Carpathian and Danube Region.

2) The more recent “Samara” theory espoused by Klochko since the 1990s (see e.g. Klochko 2017, Klochko 2019), criticizing that the “Maykop” theory ignores data from Ukraine. This data would point instead to an origin in the Samara type, spread by the Yamnaya from its Middle Dnieper cultural and technological center (hence not exactly from the Caucasus), and can be thus directly associated with the expansion of Proto-Indo-Europeans into Central Europe.

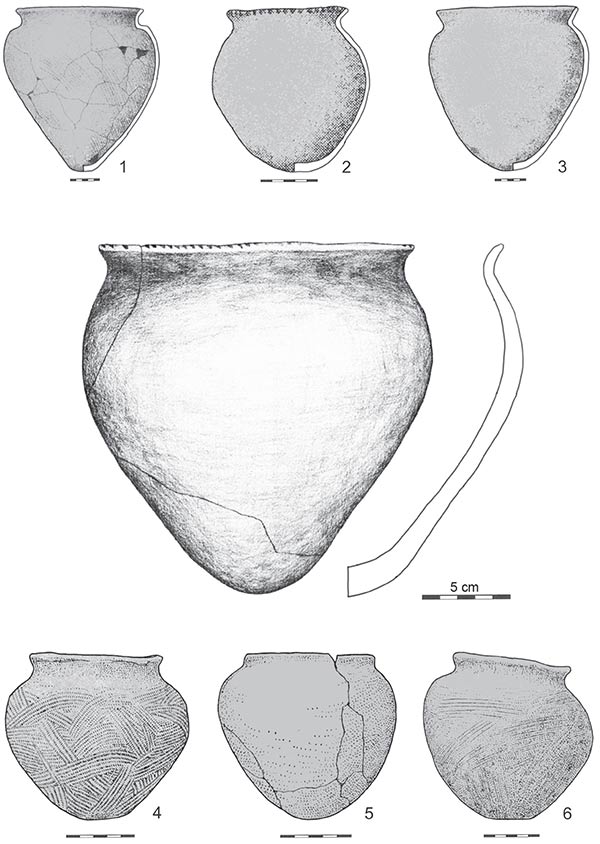

Late Yamnaya/early Catacomb vessels

A recently reported vessel from Święte appears to be linked to the late Yamnaya/early Catacomb horizon, dated to the 2nd half of the third millennium, according to Kośko et al. (2018):

The analysis of the fill of grave 1149A reveals a characteristic niche (=catacomb) construction destroyed following collapse of the ceiling of a burial chamber. In terms of spatial and chronological distribution of the CWC groups in Lesser Poland, niche structures are absolutely dominant in the younger phase [Włodarczak 2006: 53], forming the following four concentrations: Kraków, Sandomierz, Lublin (including Sokal Ridge), and Subcarpathian. The Subcarpathian one, including the site at Święte, has been only recently somewhat better understood through research preceding the implementation of road construction projects in the region of the Rzeszów Foothills and Lower San Valley.

Attributable to the older rite and finding no parallels in the CWC, vessel no. 1 exhibits stylistic features typical of the YC [Shaposhnikova 1985: Fig. 98; Shaposhnikova et al. 1986: Fig. 15]. It may be described as a pot with a pointed/oval-shaped base and a short rim decorated with diagonal stanchions impressed on the edge. A preliminary analysis of the impressions points to the use of a needle-knitted piece of textile (macroscopic analysis, courtesy of Andrzej Sikorski) [Kośko et al. 2010]. In relation to its indisputable formal ‘Yamnaya’ prototypes, the production method applied in the vessel is considered by Ukrainian experts to be ‘somewhat atypical’ as it uses a crushed stone temper (sand and crushed stone additive). It should be, however, highlighted that the outer and inner surfaces of the vessel exhibit brush strokes (so-called razchiosi involving charred residue adhering to the inner wall of the vessel). In general, such brush strokes should be viewed as a clear identifier of the ‘eastern’ topogenesis of the vessel.

For a long time, Polish literature on the CWC did not consider niche (catacomb) graves to be an identifier of exogenous traditions from the Black Sea region. The prevailing view saw them as structures convergently developed in the Baltic drainage basin [Machnik 1966; 1979]. With the most recent discoveries on the Sokal Ridge, Włodarczak does not rule out a possible revision of that view, highlighting prospective diagnostic value of the most recent fieldwork results for the ‘Dniester CWC’ [Włodarczak 2006: 135; 2014a: 21-27] as well as identified correlations with the Middle Dnieper culture [Włodarczak 2018]. What should be emphasized here is that topogenetic determinants driving various enclaves practicing the discussed ritual in the Near East and Europe have been poorly understood so far [Klejn 1967; Bratchenko 2001: 21-24; Ślusarska 2006]. The problem of ‘niche structures’ in Lesser Poland having been developed in dependence on external factors requires first a detailed analysis of their typological, chronometric, ritual and symbolic correlations with the area of the CC, or, broadly speaking, the YC and CC [Klochko, Kośko 2009; Kośko 2011].

When compared with the burial ritual of the Black Sea people, the ritual recorded in Lesser Poland comes close to that of the late YC, and early as well as classic CC (variant with bodies in a contracted position), in terms of body placement [Włodarczak 2017: 256], with the only difference being the lack of sex-related determinants in the body arrangement. However, the scarcity of data (particularly for the CC) hinders any comparison with the burial ritual practiced on that part of the Northwest Pontic region, which is located closest to Lesser Poland (upper Prut and middle Dniester areas).

A verbal opinion by Ivanova correlates this finding with a flat-base vessel associated with (?) sheep/goat meat (8 bone fragments) dug into the perimeter of the niche of Catacomb culture grave no. 4/20 at the site of Vapniarka, Kominternivske raion, Odessa oblast. Vapniarka was a ceremonial centre located at the eastern outskirts of the Budzhak group/culture territory dug into an Eneolithic barrow (central grave 4/4 dated to: Ki-15013 –4100±60 BP = 1σ 2870-2800, 2760-2560 BC), with a mound over the barrow then used for funerary purposes by the Yamnaya culture.

Indo-Iranian Pontic-Caspian steppes

This above is but a sample of what the main archaeologists in charge of excavating and interpreting the findings of the area thought, right before the Stockholm lab found these ‘archaic’ R1b-P310* dead ends (YFull is currently analyzing those with better coverage), with their elevated “Steppe ancestry”.

This proposed late arrival of Catacomb “newcomers” among disintegrating late Corded Ware groups from eastern Poland, whose influence might have reached up to Kuyavia and the South-Eastern Baltic, could help explain the multiple known Pre-Proto-Indo-Iranian loans in West Uralic, replacing thus the less straightforward Inter-Uralic long-distance contacts from Abashevo through Fatyanovo into the Battle Axe culture.

The clear cultural connection of two-wheeled-chariot-building Catacomb and Poltavka – as well as their cultural continuation into the Sintashta-Potapovka-Filatovka community under Abashevo influence – suggests a strong linguistic link between both groups. In fact, their close relationship with metallurgy and with Middle Dnieper and Abashevo groups was already particularly fitting for the strong Indo-Iranian – Disintegrating Uralic interaction, visible in vocabulary exchange relative to metalworking and mythology.

An infiltration of Early Indo-Iranians into Lesser Poland (ca. 2600-2550 BC) with cultural contacts as far as the Baltic Sea, just before their radical replacement by Bell Beakers (ca. 2400 BC on) and derived Mierzanowice and Trzciniec groups, could also help explain any proposed ancestral similarity or loanword shared by Balto-Slavic with Indo-Iranian, if there had been any not directly attributable to the Disintegrating Indo-European-speaking Yamnaya stage, or to much later contacts with Iranian-speaking groups.

Even more interesting, it could help us dismiss once and for all the potential nature of Catacomb as “Palaeo-Balkan”-speaking, confirming thus the expansion of Palaeo-Balkan languages with the spread of Yamnnaya settlements in South-Eastern Europe. That would also leave the Armenian branch either to the south of Indo-Iranians, within the North Caucasus community, or among Palaeo-Balkan groups. It also helps reject any proposal of survival or late influence of Corded Ware-derived groups anywhere, except for North-Eastern Europe, where Uralic languages thrived during the Bronze Age.

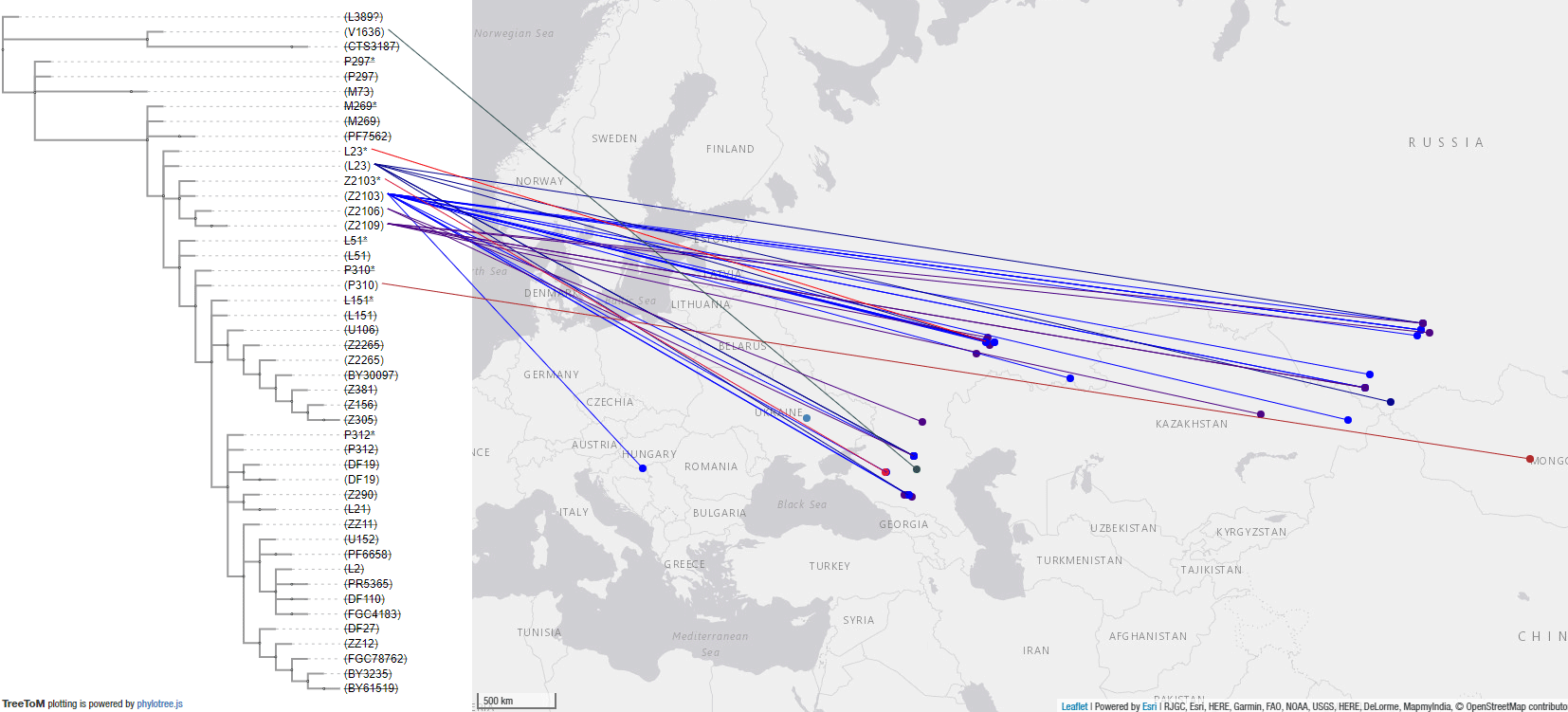

Since the finding of R1b-P310 in Afanasievo, it has become crystal clear – if it wasn’t already – that (1) the bottlenecks of R1b-M269 leading to the subsequent spread of R1b-L23 lineages were clearly associated with the Proto-Indo-European expansions, and that (2) there is no clear-cut distribution of R1b-L51 and R1b-Z2103 among Late PIE dialects, as I first proposed; especially not for ‘archaic’ lineages. Therefore, there is no reason why R1b-L51 subclades could not be found among early Indo-Iranians from the steppes, given the currently available ancient phylogeography of R1b. In fact, the finding of diverse R1b-L23 subclades among early Palaeo-Balkan-speaking peoples will easily confirm their association with the Graeco-Aryan group, too.

NOTE. I thought in 2016 that R1b-L51 would have been the main marker of Repin expansions, potentially ‘joining forces’ in Middle Volga territory with a majority of late Khvalynsk-derived R1b-Z2103-rich clans, before expanding as R1b-Z2103-rich Indo-Iranians. While this is a 2000s-like approach to a much more complex process of succeeding bottlenecks and admixture events, it is nevertheless funny to find out that even now it makes sense.

It appears as if there had been a growing consensus among Polish and Ukrainian archaeologists regarding recent cultural influences of Pontic origin before Linderholm et al. (2020), with researchers proposing potential migration waves, a question that should have been resolved by population genomics. Seeing how Corded Ware groups show increasing admixture with Neolithic populations over time, and how sampled late groups reflect the infiltration or resurgence of “local” lineages everywhere from ca. 2600 BC or earlier – even without a trace of cultural change (as in Switzerland or Poland) – and how this Małopolska population of marked Catacomb-like traits shows a Yamnaya-related haplogroup, it is plausible that the samples – when properly released – will show a direct Yamnaya-like (i.e. Catacomb-related) influence in terms of ancestry, something not found in most early Corded Ware groups.

Nevertheless, these late communities will no doubt show local admixture, hence their position in the PCA similar to early Corded Ware from Poland. In that sense, we might be in front of a case similar to the late Yamnaya or Catacomb outlier from Dereivka, I5884 (ca. 2890-2696 calBCE), of hg. R1b-Z2103, with WHG-like ancestry profile; and to many Bell Beakers heavily admixed through exogamy with local populations, such as Corded Ware-, EEF- or WHG-related peoples. But still, it will be interesting to see how much Yamnaya ancestry these groups actually have compared to R1a-rich early Corded Ware samples from Poland and to R1a-rich Late Trypillians of high steppe ancestry.

It is important to keep in mind that Lesser Poland appears to be the sink of many different (eastward and westward) steppe-related migration waves during the Eneolithic and the Early Bronze Age, including at least Late Trypillia-related, Yamnaya-related, Catacomb- and Middle Dnieper-related ones, apart from the final East Bell Beaker waves that radically replaced them all, so the specifics of their genetic and cultural origin and impact are far from clear. What is certain is that the Podolian-Volhynian Upland is at the core of early Indo-European – Uralic contacts, so no particular language contact scheme can be discarded just yet.

In any case, it is striking that co-authors like Włodarczak, who recently started to accept the likelihood of renewed waves of Pontic-related migrations into late Corded Ware territory (as supported by isotopic studies) by collaborating with Ukrainian researchers, had a sudden change of heart, and decided that these genetic findings could help bring “continuity” (as traditionally defended by Polish archaeologists) back to life instead. Even stranger is the proposal of a hypothetical expansion of R1b-L51 lineages earlier with Corded Ware “through the Uplands”, when not even a single R1b-L23 subclade has been found to date among Corded Ware peoples, and it is becoming more and more unlikely to be found.

My guess is that, similar to the case of scarce and late infiltration of hg. N1c in North-Eastern Europe only during the Iron Age and later, we are just seeing the tip of the iceberg of how much damage that wrong interpretation of “Yamnaya ancestry” from the 2015 papers can do, especially when combined with the traditionalist trend to defend an outdated concept of Kurgan peoples, and with the natural confirmation bias displayed by most local archaeologists regarding national “continuity” narratives.

See also

- The Corded Ware culture, more complex than previously thought

- Yamnaya ancestry: mapping the Proto-Indo-European expansions

- Early Uralic – Indo-European contacts within Europe

- Intense but irregular NWIE and Indo-Iranian contacts show Uralic disintegrated in the West

- R1b-rich Proto-Indo-Europeans show genetic continuity in Asia

- Corded Ware ancestry in North Eurasia and the Uralic expansion

- “Steppe ancestry” step by step (2019): Mesolithic to Early Bronze Age Eurasia

- Bell Beakers and Mycenaeans from Yamnaya; Corded Ware from the forest steppe

- East Bell Beakers, an in situ admixture of Yamna settlers and GAC-like groups in Hungary

- Yamnaya replaced Europeans, but admixed heavily as they spread to Asia