Investigating the kinship between individuals deposited in exceptional Merovingian multiple burials through aDNA analysis: The case of Hérange burial 41 (Northeast France), by Deguilloux et al. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports (2018) 20:784-790.

Interesting excerpts (emphasis mine):

The Merovingian period in Northeast France (developing from 440/450 to 700/710 CE; Legoux et al., 2004) represents [a case of multiple burial], where a large majority of the types of deposits encountered consists of individual burials. In this context, whereas hundreds of individual burials are known, the syntheses recently conducted have enabled the inventory of only six multiple burials (Lefebvre and Lafosse, 2016). These observations naturally raised questions about the exceptional circumstances that led the members of the community to set up such unusual burials. The archaeological site of Hérange, excavated in 2014 (Lorraine, Grand Est region; Fig. S1), holds a key position in the debate surrounding the interpretation of multiple burials during the Merovingian period since it contains one of these rare multiple burials: burial 41, which was dated through archaeological material to the period 530–640 CE.

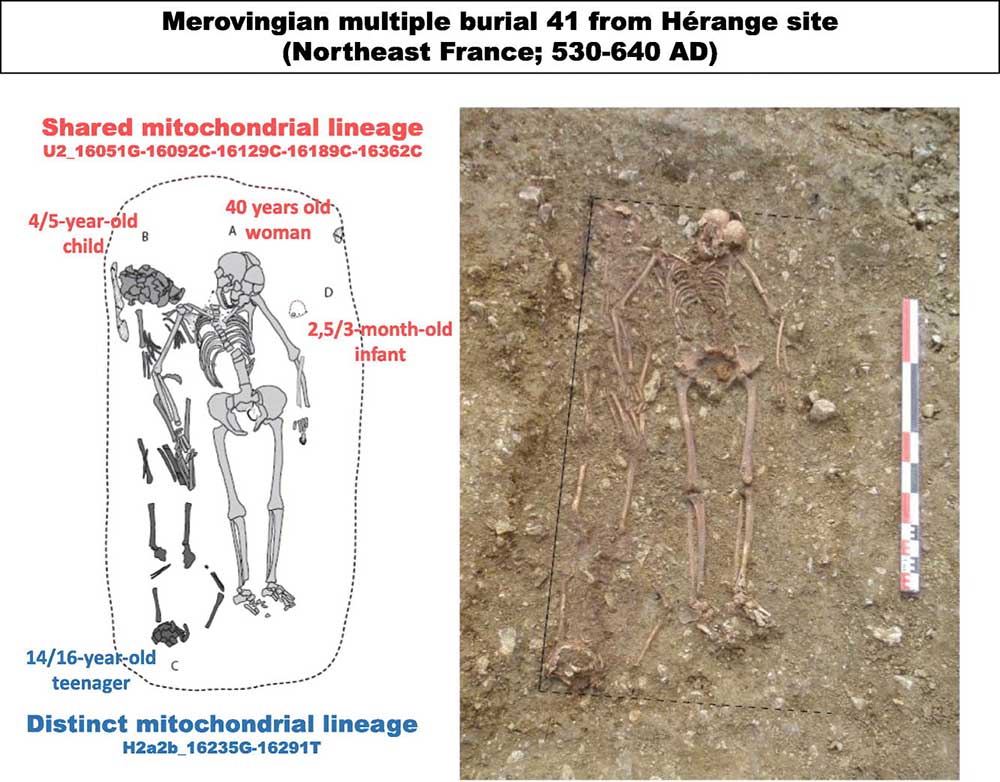

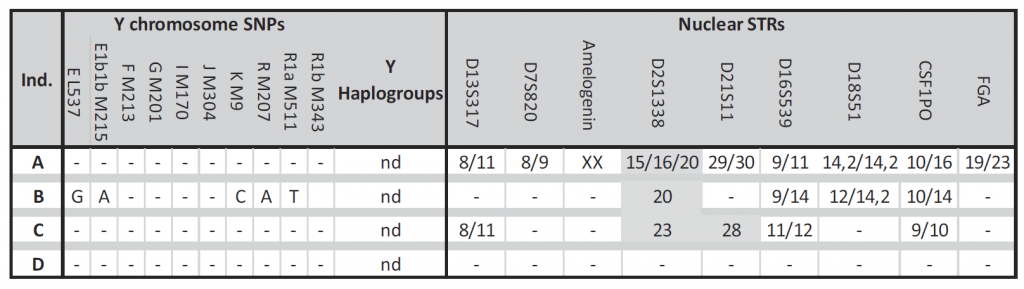

(…) The biological analysis of the human remains recovered in the second burial (“burial 41”) enabled the demonstration of the combined presence of a woman of approximately 40 years old (A) and three immature individuals, including a 4–5-year-old child (B), a 14–16-year-old teenager (C) and a 2,5–3-month-old infant (D) (Lefebvre and Lafosse, 2016) (Fig. 1). Since rare multiple burials described for the Merovingian period in Northeast France mainly contained two or rarely three deceased, the discovery of a burial grouping four individuals reinforced its exceptional nature. (…) Intriguingly, great care was observed in the treatment of the dead, as illustrated through a special arrangement of the deceased in the grave (Fig. 1). Indeed, the woman A occupied a central position in the grave, with her left arm covering part of the body of child D, her right arm covering the torso of child B and her right hand covering the legs of children B and C. Several arguments, such as the close contact or the imbrication of the bones of individuals A, B and C, have attested to the simultaneity of their deposits in the burial (Lefebvre and Lafosse, 2016).

Interestingly, studies have demonstrated an important chronological homogeneity for the rare multiple burials discovered for the Merovingian period in the Lorraine region (Lefebvre and Lafosse, 2016). The collected data support the existence of an epiphenomenon arisen around the middle of the Merovingian period and that may have linked the multiple burials to (i) a funerary “fashion trend” for a special group of the community, (ii) an increase in cases of violence or (iii) an epidemic crisis linked to infectious disease. In other Lorraine sites, none of the available indices permitted the specification of the cause of death for the individuals recovered in these specific burials. The deceased could well have died of natural causes, violent acts or infectious diseases that had left no visible evidence on the skeletal.

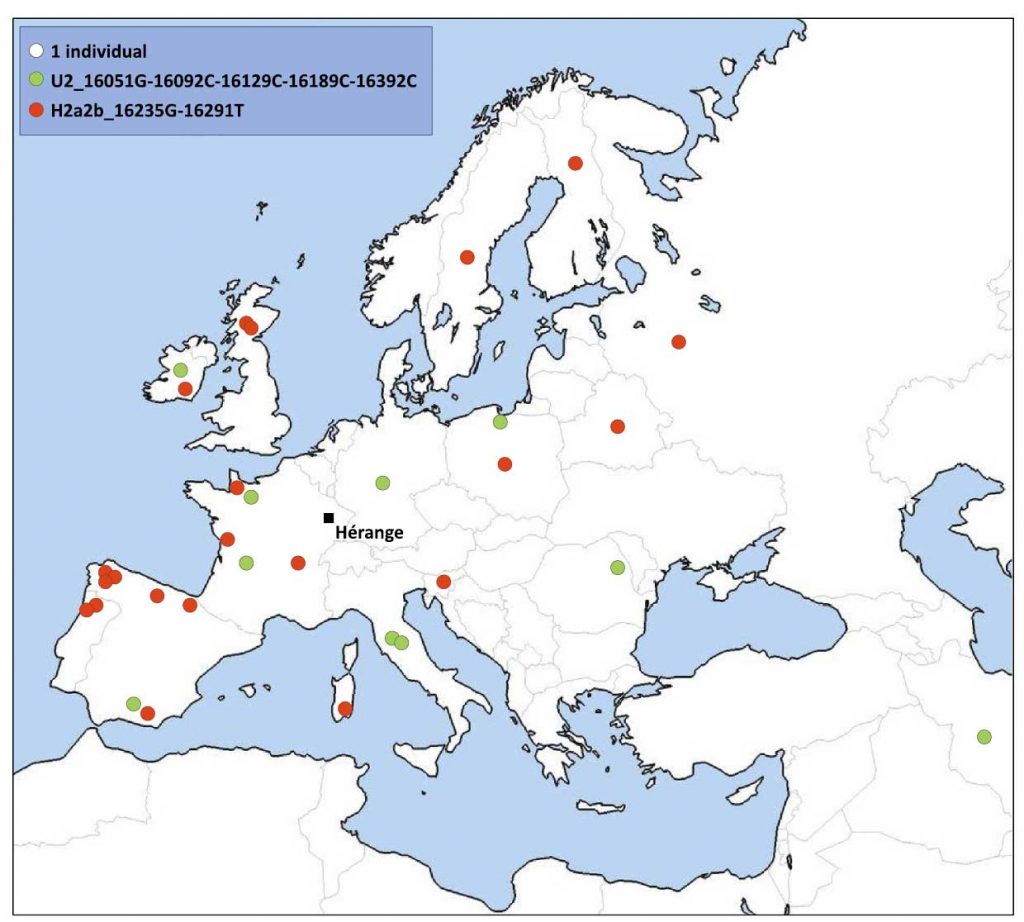

The aDNA analyses conducted on the four individuals discovered in the exceptional multiple burial 41 from Hérange (Lorraine) have demonstrated strong biological links between three individuals. Notably, we could propose that the woman A was the mother of the two immatures B and D deposited just besides her whereas she was not genetically closely related to the teenager C deposited along her legs. Consequently, we propose that the special arrangement of the deceased in the grave clearly reflected the degree of biological links between the deposited individuals. In Hérange, the bereaved were well aware of kinship among the deceased, wanted to express this close linkage through their relative location within the burial, and intentionally arranged body positions consequently. In conclusion, the collected archaeological, archaeo-anthropological and genetic data suggest that the special setup of the multiple burial 41 in the Hérange necropolis and the great care in the treatment of the dead, could be explained by the contemporaneous death of the four related individuals. Data gathered for other archaeological sites from the region or in Germany suggested an epidemic crisis (plague epidemic?) during the middle of the Merovingian period that may explain the contemporaneous death of related individuals living in close contact and easily sharing pathogens.

Reported mtDNA haplogroups include U* for samples A, B, and D, and H for sample C.

Related:

- Reproductive success among ancient Icelanders stratified by ancestry

- Genomic analysis of Germanic tribes from Bavaria show North-Central European ancestry

- Germanic tribes during the Barbarian migrations show mainly R1b, also I lineages

- mtDNA suggest original East Germanic population linked to Jutland Iron Age and Bell Beaker

- Admixture of Srubna and Huns in Hungarian conquerors

- The concept of “Outlier” in Human Ancestry (III): Late Neolithic samples from the Baltic region and origins of the Corded Ware culture

- Genetic prehistory of the Baltic Sea region and Y-DNA: Corded Ware and R1a-Z645, Bronze Age and N1c

- Bell Beaker/early Late Neolithic (NOT Corded Ware/Battle Axe) identified as forming the Pre-Germanic community in Scandinavia

- The Tollense Valley battlefield: the North European ‘Trojan war’ that hints to western Balto-Slavic origins