Open access research highlight A history of male migration in and out of the Green Sahara, by Yali Xue, Genome Biology (2018) 19:30, on the recent paper by D’Atanasio et al.

Insights from the Green Saharan Y-chromosomal findings (emphasis mine):

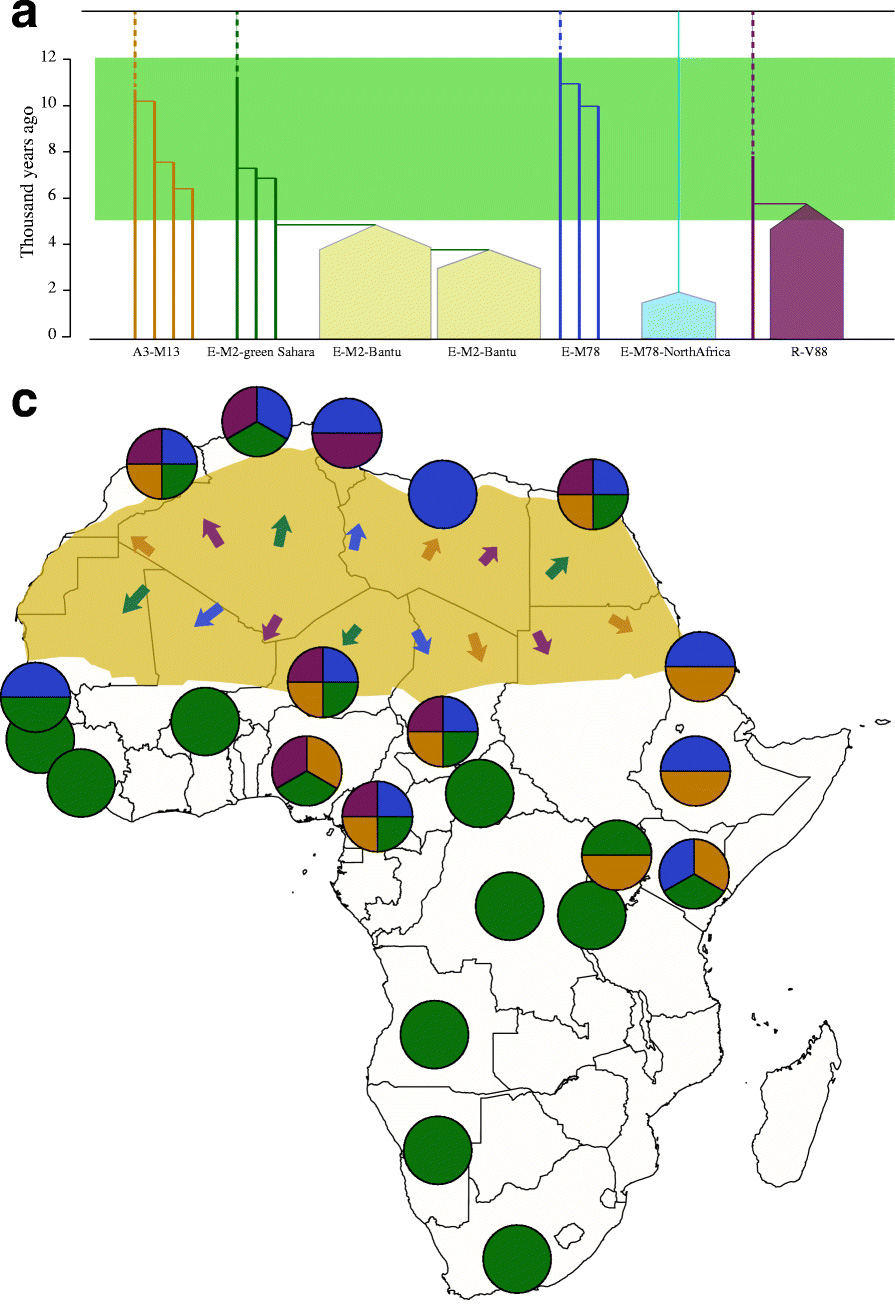

It is widely accepted that sub-Saharan Y chromosomes are dominated by E-M2 lineages carried by Bantu-speaking farmers as they expanded from West Africa starting < 5 kya, reaching South Africa within recent centuries [4]. The E-M2-Bantu lineages lie phylogenetically within the E-M2-Green Sahara lineage and show at least three explosive lineage expansions beginning 4.9–5.3 kya [5] (Fig. 1a). These events of E-M2-Bantu expansion are slightly later than the R-V88 expansion, and highlight the range of male demographic changes in the mid-Holocene. North of the Sahara, in addition to the four trans-Saharan haplogroups, haplogroup E-M81 (which diverged from E-M78 ~ 13 kya) became very common in present-day populations as a result of another massive expansion ~ 2 kya [6] (Fig. 1a).

Although Y chromosomes exist within populations and so share and reflect the general history of those populations, they can sometimes show some departures from other parts of the genome that result from differences in male and female behaviors. D’Atanasio et al. [1] highlight one such contrast in their study. Present-day North African populations show substantial sub-Saharan autosomal and mtDNA genetic components ascribed to the Roman and Arab slave trades 1–2 kya [7], but carry few sub-Saharan Y lineages from this source, probably reflecting the smaller numbers of male slaves and their reduced reproductive opportunities when compared to those of female slaves. The sub-Saharan Y chromosomes in these North African populations thus originate predominantly from the earlier Green Sahara period.

In this part of Africa, the indigenous languages that are spoken belong to three of the four African linguistic families (Afro-Asiatic, Nilo-Saharan and Niger-Congo). Interestingly, these languages show non-random associations with Y lineages. For example, Chadic languages within the Afro-Asiatic family are associated with haplogroup R-V88, whereas Nilo-Saharan languages are associated with specific sublineages within A3-M13 and E-M78, further illustrating the complex human history of the region.

The main question after D’Atanasio et al. (2018) is thus:

(…) what are the reasons for the very rapid R-V88 expansion 5–6 kya [1] and E-M81 expansion ~ 2 kya [6], and how do these expansions fit within general worldwide patterns of male-specific expansions, which in other cases have been linked to cultural and technological changes [5]?

I think that the only known haplogroup expansion that might fit today the spread and dialectalization of Afroasiatic, a proto-language probably contemporaneous or slighly older than Middle Proto-Indo-European, is that of R1b-V88 lineages. However, without ancient DNA samples to corroborate this, we cannot be sure.

See also:

- R1b-V88 migration through Southern Italy into Green Sahara corridor, and the Afroasiatic connection

- Potential Afroasiatic Urheimat near Lake Megachad

- The arrival of haplogroup R1a-M417 in Eastern Europe, and the east-west diffusion of pottery through North Eurasia

- The Indo-European demic diffusion model, and the “R1b – Indo-European” association

- Expansion of peoples associated with spread of haplogroups: Mongols and C3*-F3918, Arabs and E-M183 (M81)

- Archaeological origins of Early Proto-Indo-European in the Baltic during the Mesolithic

- Genetic landscapes showing human genetic diversity aligning with geography

- Human ancestry solves language questions? New admixture citebait