As you can see from my interest in the recently published Olalde et al. (2019) Iberia paper, once you accept that East Bell Beakers expanded North-West Indo-European, the most important question becomes how did its known dialects spread to their known historic areas.

We already had a good idea about the expansion of Celts, based on proto-historical accounts, fragmentary languages, and linguistic guesstimates, but the connection of Celtic with either Urnfield or slightly later Hallstatt/La Tène was always blurred, due to the lack of precise data on population movements.

The latest paper on Iberia is interesting for many details, such as:

- The express dismissal of the newest pet theory based on the simplistic “steppe ancestry = IE”: the obsessive comparisons of Dutch Bell Beakers as the origin of basically anything that moves in Europe.

- A discrete influx of North African ancestry in certain samples before the Moorish invasion (which was probably mediated by peoples of North African rather than Levantine admixture).

- The finding of very Mycenaean-like Greek colonies of the 5th century (interestingly, under R1b lineages).

The paper is, however, of particular importance from the perspective of historical linguistics. It confirms that:

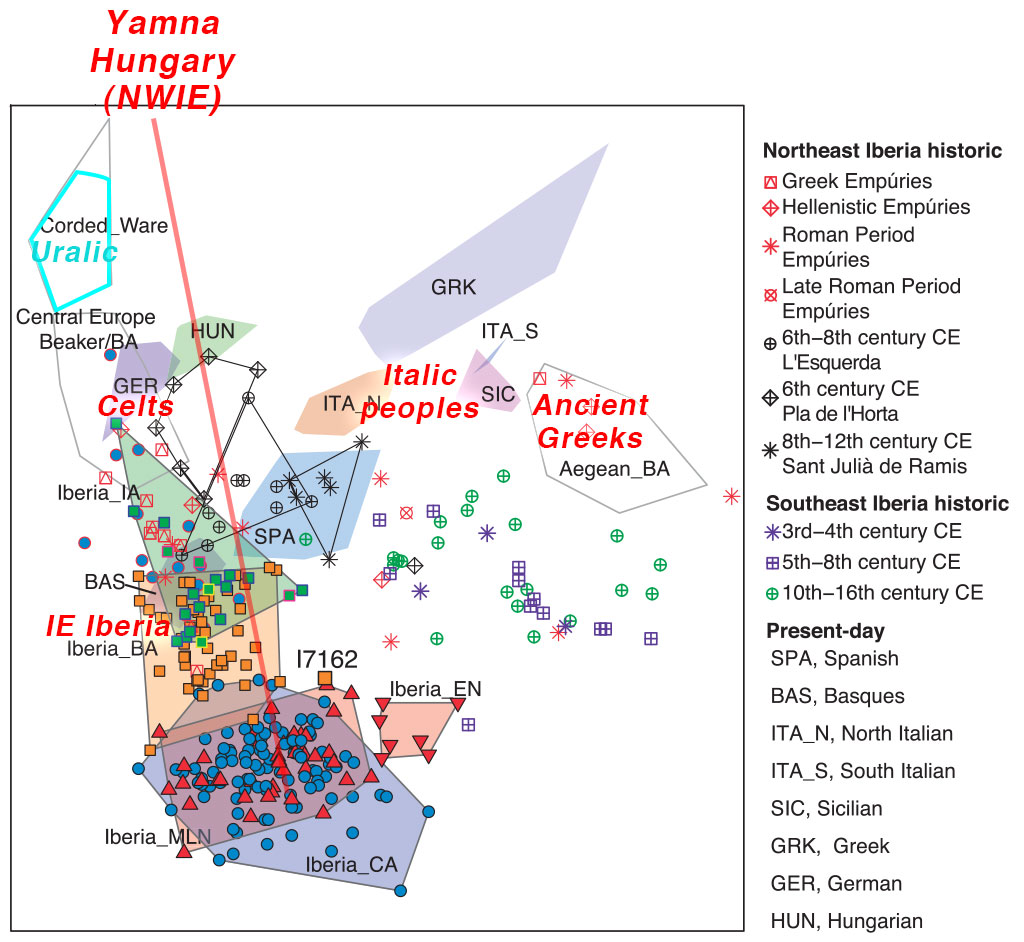

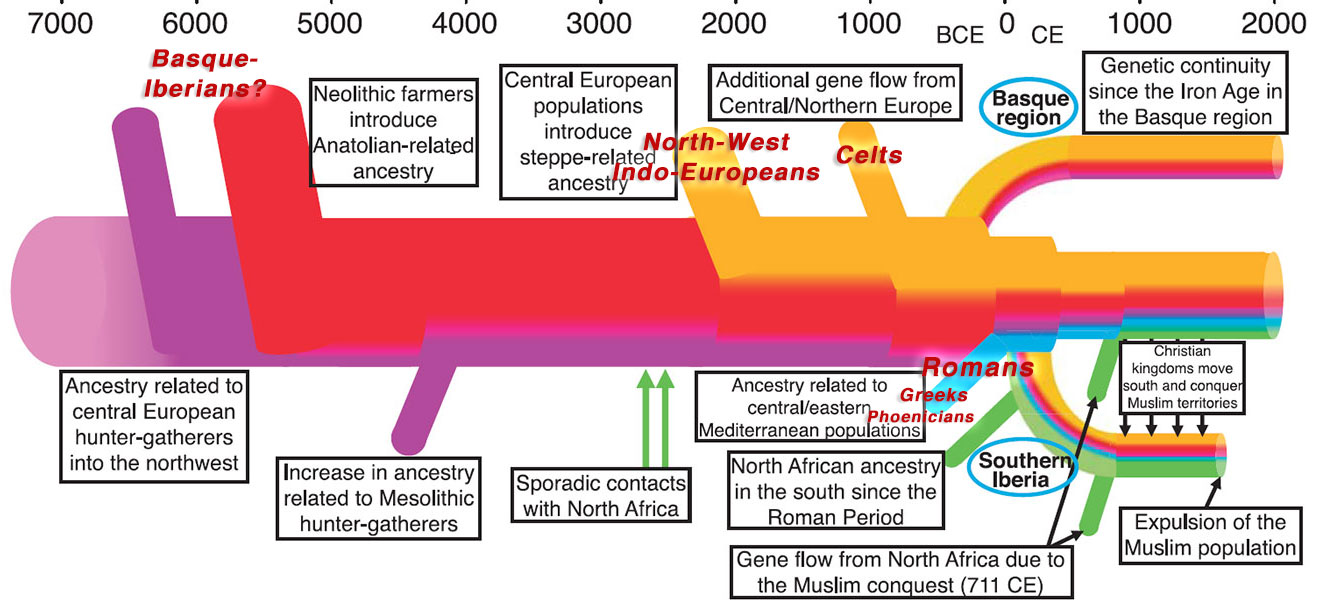

- Celtic-speaking peoples expanded in Iberia likely during the Late Bronze Age – Early Iron Age (probably with the Urnfield culture, before 1000 BC) with North/Central European ancestry.

NOTE. The paper marks what are believed to be the boundaries of non-Indo-European languages during the Iron Age in later times, extrapolating that situation to the past. Mediterranean sites with Iberian traits (ca. 6th century on) were probably non-Indo-European-speaking tribes, but it is unclear what happened in the centuries before their sampling, and there are no clear boundaries. These incoming Celts from central Europe with the Urnfield culture makes it very likely that the Iberian expansion to the north happened later, incorporating thus this central European ancestry in the process. The southern (orientalizing, Tartessian) site of La Angorrilla shows incineration and influence from Phoenician settlers, and their actual language is also far from clear. The other investigated samples, with higher central European contribution, are from Celtiberian sites.

- The slightly later arrival of (Phoenician, Greek and) Latin-speaking peoples into Iberia is marked by Central/Eastern Mediterranean and North African ancestry.

While both confirm what was more or less already known about the oldest attested NWIE dialects, and further support the role of East Bell Beakers in expanding North-West Indo-European, the first part is interesting for two main reasons:

- Koch’s Celtic from the West hypothesis, which made a recent comeback with a renewed model based on “steppe ancestry”, is once again rejected in population genomics, as expected. At this point I doubt this will mean anything to the supporters of the theory (because you can propose as many “Celtic-over-Celtic” layers as you want), but if you are not obsessed with autochthonous continuity of Celtic languages in the Atlantic area we might begin to judge the most correct dialectal split (and thus classification) among those proposed to date, based on ancestry and haplogroup expansions.

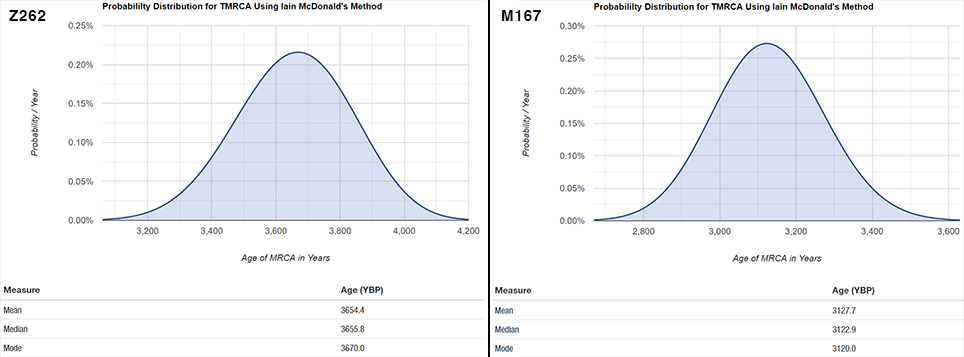

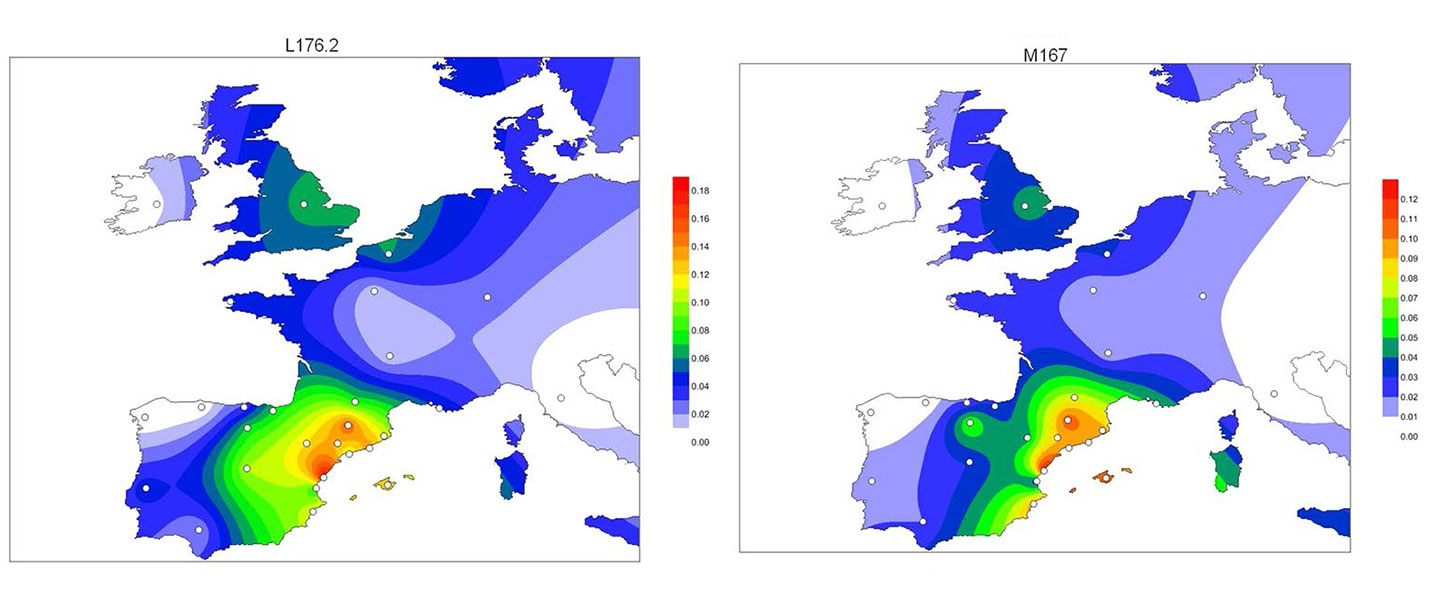

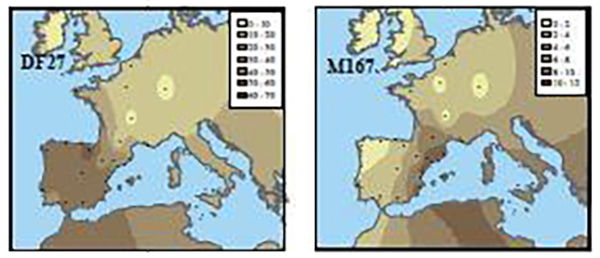

- We believed in the 2000s that the expansion of haplogroup R1b-M167 (TMRCA ca. 1100 BC for YTree or 1700 BC for YFull) was coupled with the expansion of Iberians from the Pyrenees, in turn (thus) closely related to Basques. This non-IE presence has been contested with toponymic data in linguistics, and with the testing of many modern samples and the subsequent discovery of the widespread distribution of the subclade in western and northern Europe. Now it has become even more likely (lacking confirmation with aDNA) that this haplogroup expanded with Celts.

NOTE. Regarding R1b SNPs, YTree has more samples (and thus more SNPs) to work with estimates, due to its connection with FTDNA groups, so it is in principle more reliable (although estimates were calculated in 2017). Nevertheless, the methods to estimate the age of the MRCA are different between YTree and YFull.

Why this is important has to do with the realization that Celts must have expanded explosively in all directions during the estimated range for Common Celtic (ca. 1500-1000 BC), and as such R1b-M167 is probably going to be one of the clear Y-DNA markers of the Celtic expansion, when it appears in the ancient DNA record, maybe in new SNP calls from samples of the Olalde et al. (2019) paper, or in future Urnfield/Hallstatt/La Tène papers.

Sister clades derived from R1b-Z262 (TMRCA ca. 1650 BC for YTree, or 2700 for YFull), although sharing a quite old origin, may have taken part in the same communities that expanded R1b-M167, likely from some point in central Europe, possibly as remnants of a previous (Tumulus culture?) central European expansion, as the sample SZ5 from Szólád (R1b-CTS1595) and the distribution of modern samples suggest.

EDIT (23 APRIL): In Hernández et al. (2018), the TMRCA of R1b-M167 is reported as 3372-3718 ybp:

The youngest sub-branch, R1b-M167, dates to approximately 3.5 kya (95% CI= 2.5-5.3 kya), i.e. even after the Bronze Age.

NOTE. Admittedly, the maps are mainly based on Iberian samples and certain limited sampling elsewhere, so most of the frequencies displayed in other territories are extrapolated. Since the percentage of R1b-M167 in France is estimated to be ca. 3%, and in Bavaria ca. 5%, the distribution in Central Europe is probably much higher, and around the Mediterranean much lower than represented in them.

The Celtic expansion might not have been a mass migration of peoples replacing all male lines of their controlled territories (as was common in the Neolithic and Chalcolithic), because of the Bronze Age dominant chiefdom-based system that relied on alliances, but it is becoming clear that Early Celts are also going to show the expansion of certain successful male lineages.

Oh, and you can say goodbye to the autochthonous “Vasconic = R1b-DF27” (latest heir of the “Vasconic = R1b-P312”) theory, too, if – for some strange reason – you hadn’t already.

EDIT (16 MAR) Just in case the wording is not clear: the fact that this haplogroup most likely expanded with Celts does not mean that its lineages didn’t become eventually incorporated into Iberian cultures and adopted non-IE languages: some of them probably did at some point, in some regions of northern Iberia, and most were certainly later incorporated to the Roman civilization and spoke Latin, then to the medieval kingdoms with their languages, and so on until the present day… Only those eventually associated with Iron Age Aquitanians may have retained their non-IE language, unless those lineages today associated with Basques were incorporated later to the Basque-speaking regions by expanding medieval kingdoms. A complex picture repeated everywhere in Europe: no haplogroup+language continuity in sight, anywhere.

NOTE: This here is currently the most likely interpretation of data based on estimations of mutations; it is not confirmed with ancient samples.

Related

- Iberia: East Bell Beakers spread Indo-European languages; Celts expanded later

- Analysis of R1b-DF27 haplogroups in modern populations adds new information that contrasts with ‘steppe admixture’ results

- On Latin, Turkic, and Celtic – likely stories of mixed societies and little genetic impact

- First Iberian R1b-DF27 sample, probably from incoming East Bell Beakers

- Patterns of genetic differentiation and the footprints of historical migrations in the Iberian Peninsula

- First Iberian R1b-DF27 sample, probably from incoming East Bell Beakers

- Iberian prehistoric migrations in Genomics from Neolithic, Chalcolithic, and Bronze Age

- Cogotas I Bronze Age pottery emulated and expanded Bell Beaker decoration

- David Reich on social inequality and Yamna expansion with few Y-DNA subclades

- Distribution of Southern Iberian haplogroup H indicates exchanges in the western Mediterranean

- Population substructure in Iberia, highest in the north-west territory (to appear in Nature)

- Analysis of R1b-DF27 haplogroups in modern populations adds new information that contrasts with ‘steppe admixture’ results