New paper (behind paywall), Eurasian Steppe Chariots and Social Complexity During the Bronze Age, by Chechushkov and Epimakhov, Journal of World Prehistory (2018).

Interesting excerpts (emphasis mine):

Nowadays, archaeologists distinguish at least three Bronze Age pictorial traditions on the basis of style, and demonstrate some parallels in the material culture. The earliest is the Yamna–Afanasievo tradition, which is characterized by the symbolic depiction of sun-headed men and animals. Another tradition is a record of the Andronovo people (Kuzmina 1994; Novozhenov 2012), who depicted in it their everyday life and the importance of wheeled transport (Novozhenov 2014a, b). Although petroglyphs on open-air natural rock surfaces are obviously hard to date, the occurrence of similar carvings on stone grave stelae within some Andronovo culture cemeteries (such as the Tamgaly Cemetery and the Samara Cemetery in Sary Arka, Kazakhstan) provide a level of chronological control. Finally, the finds of petroglyphs depicting chariots in the burials of the Karasuk culture (c. 1400–800 BC) in southern Siberia and Kazakhstan allow us to distinguish the latest tradition (Novozhenov 2014b).

The site of Sintashta in the steppe zone of the Southern Trans-Urals (the eastern side of the Ural Mountains) was excavated in the 1970s and yielded abundant Bronze Age material, including unparalleled evidence of six vehicles buried in graves, each with two spoked wheels accompanied by cheekpieces and sacrificial horses (Gening 1977; Gening et al. 1992). (…) Chariot remains from the Middle and Late Bronze Age in the southern Urals are quite abundant compared with early chariot remains from other parts of the world, and allow statistical analysis.

In contrast, only two wagons and one sledge were found in the Royal Cemetery of Ur (Woolley 1965), and only ten actual chariots and their parts are known from tombs of the New Kingdom of Egypt (1550–1069 BC) (Littauer and Crouwel 1985; James 1974; Herold 2006), with the rest of the information on the Near Eastern chariots coming in other forms. Two chariots and the wheels of a third were also found in the Lchashen Cemetery in Armenia (Yesayan 1960), dated to 1400–1300 BC (Pogrebova 2003, p. 397), and bronze models of chariots were found in the burial sites of neighboring Transcaucasia (Brileva 2012). Over one hundred chariots have been discovered in Shang period tombs in China, but none dates before 1200 BC (Wu 2013).

Sintashta–Petrovka chariots were functional and used for carrying passengers and, probably, for warfare. Otherwise, one would not expect to see consistency in the measurements and technological solutions (…)

(1) The technological solutions used to construct a wheel and its dimensions are derived from the measurements of the ‘wheel pits’. They allow such analysis because some had the actual imprints of felloes and spokes. (…) Due to the imprints of spokes and felloes left in the soil, it is clear that the Bronze Age people knew of and utilized the spoked wheel.

(2) Wheel track is the distance between the centerlines of two wheels on an axle. It can be estimated on the basis of the distance between the central axes of all known wheel pits, in addition to direct measurement of the eight known cases of wheel imprints.(…) the majority of findings with a mean wheel track of 136 ± 12 cm might represent either a single-driver chariot or a vehicle with two passengers who accessed the vehicle from the rear, since one extreme of this wheel-track provides enough space for a standing person, while another is suitable for a driver and passenger.

(3) The means of traction is the element that connects the vehicle to the yoke of the draft animals (Littauer et al. 2002, p. xvii). It is needed for a vehicle to be pulled by harnessed animals and is constructed as a central draft pole located between the animals, or shafts located on the external sides of the animals, called thills. (…) Using burial chamber size as a proxy, chariots had a maximum estimated length of 327 ± 20 cm, and a maximum estimated width of 205 ± 21 cm. These dimensions suggest a great similarity to six chariots of Tutankhamun that have maximum dimensions of 260 × 236 cm (Crouwel 2013).

Associated individuals

suggest that this person was a chief, and that the burial context illustrates his significance in the social life of the local community (Logvin and Shevnina 2008, p. 193). However, it also suggests the diverse role of the Sintashta–Petrovka elites, who were likely engaged in a number of different activities, such as warfare, craft production, food production, and a broad social life.

(…) while weapons are not universally present with chariots, they are present much more often than in non-chariot burials: more than 50% of the chariot burials are accompanied by weapons, with a clear predominance of projectile arms.

The creation, utilization, and maintenance of the chariots would have required a number of important skills, and some degree of standardization in manufacturing chariots might be related to a very small number of chariot makers. This means that the Sintashta–Petrovka craftsmen were ‘attached specialists’ and made their products following the orders and desires of those who were interested in the competitive use of chariots. Hence, the social group interested in producing and maintaining chariots sponsored all of those processes. While the nature of this social group is unclear, it is reasonable to hypothesize that it could be a group of military elites characterized by aggrandizing behavior. These people shared military identities and values, but also belonged to bigger collectives, presumably diverse kin groups. The competition between these collectives for resources, power, and prestige created the chariot complex.

Evolution

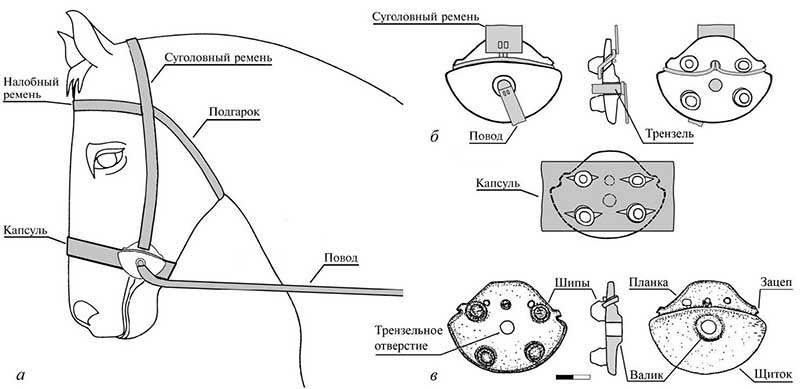

Analyzing horse-headed knobs, Kovalevskaya demonstrates the evolution of horse tack from a simple muzzle to a bridle with bits during the 5th and 4th millennia BC (Kovalevskaya 2014). Her analysis correlates well with a study of pathologies in horse teeth conducted by Brown and Anthony, who suggest the appearance of bits and horseback riding at Botai and Tersek (Anthony et al. 2006). Cheekpieces became the next necessary and logical step in the evolution of means of horse control. Their appearance together with the wheeled vehicles is not a coincidence, but the development of preceding tools. After the year 2000 BC, cheekpieces often occur together with sacrificed horses—13 out of 15 Sintashta burials with cheekpieces also contain horse bones (Epimakhov and Berseneva 2012)—showing evolution in the role of horses.

The whole paper offers an interesting summary of cultural and population events in the Pontic-Caspian steppes since the Early Yamna period. Also, horse-headed knobs!

NOTE. You can find similar information in other (free) papers from Chechushkov in his account in Academia.edu.

Related

- The origin of social complexity in the development of the Sintashta culture

- Sintashta diet and economy based on domesticated animal products and wild resources

- Sintashta-Petrovka and Potapovka cultures, and the cause of the Steppe EMBA – MLBA differences

- Pasture usage by ancient pastoralists in Middle and Late Bronze Age Kazakhstan

- Fast life history as adaptive regional response to less hospitable and unstable Early Indo-Iranian territory

- Consequences of Damgaard et al. 2018 (III): Proto-Finno-Ugric & Proto-Indo-Iranian in the North Caspian region

- Eurasian steppe dominated by Iranian peoples, Indo-Iranian expanded from East Yamna

- No large-scale steppe migration into Anatolia; early Yamna migrations and MLBA brought LPIE dialects in Asia

- Early Indo-Iranian formed mainly by R1b-Z2103 and R1a-Z93, Corded Ware out of Late PIE-speaking migrations

- Y-DNA haplogroup R1b-Z2103 in Proto-Indo-Iranians?