Interesting press release from the Institute of Archaeology at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań:

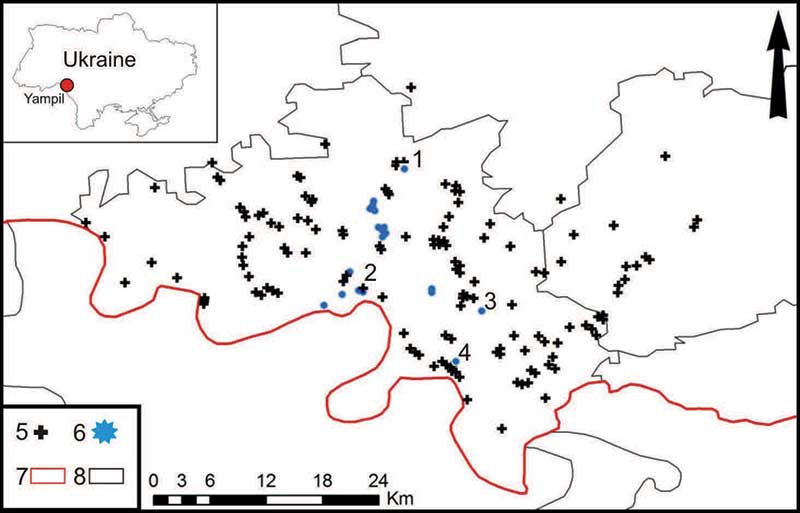

In an open access report last year, Anthropological Description of Skeletal Material from the Dniester Barrow-cemetery Complex, Yampil Region, Vinnitsa Oblast (Ukraine), the team lead by Liudmyla Litvinova – of the Ukrainian Academy of Science – published their findings from the skeletons in different burial mounds along the border with Moldavia, ranging from Eneolithic to Iron Age burials.

In one Yamnaya burial rested a young woman aged 25-30. It was so described in the original paper:

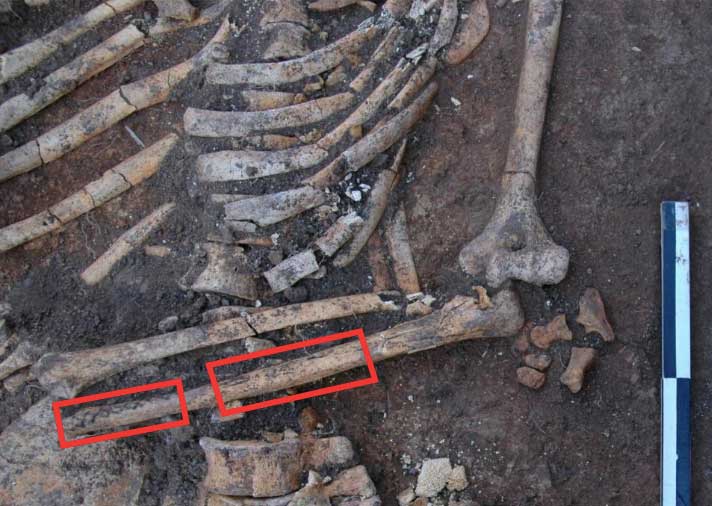

Barrow 3A, feature 10. A very poorly-preserved skeleton with a badly damaged skull. The preserved bones include small fragments of the cranial vault and mandible and larger ones of the upper and lower limbs, pelvis fragments and vertebrae. The skeleton belonged to a female aged 25-30 years (adultus). Due to the poor state of preservation of long bones, it was not possible to reconstruct her stature. Palaeopathological lesions: LEH on both lower canines (age of the individual at the time of both defects: 4.5-5.0 years); caries on the upper left third molar.

This is what the team has discovered since then:

While drawing and photographing the burial, our attention was drawn to regular patterns, such as parallel lines visible on both elbow bones. At first, we approached the discovery with caution – maybe the traces were left by animals, we wondered

– Says Danuta Żurkiewicz from the Institute of Archaeology, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, who prepared an article on the decorations.

It is surprising that the procedure of decorating the bones had to be done after death and the process of body decomposition. This is clearly indicated by the location of the decoration on the bone surface and the way dye was applied.

Some time after the woman’s death the grave was reopened, bone decoration was performed and the bones were re-arranged in anatomical order.

According to Żurkiewicz, this discovery is unique – so far, no comparable custom among other prehistoric communities in Europe has been recorded.

Until now, the few similar discoveries have been interpreted as remnants of tattoos, but none of them have been analysed using so many modern methods, which is why they can not be confirmed with full confidence

Żurkiewicz believes that:

However, women were rarely buried in them. The deceased, whose bones were covered with patterns, had to be an important member of the community.

These findings will be detailed in volume 22 of Baltic-Pontic Studies, which will be available online on the De Gruyter Open platform in August.

My opinion – without knowing anything about the case, site, or archaeology of kurgans in general, just from my knowledge in Orthopaedic Surgery – is that it would be quite easy to make those marks on the cubitus post-mortem, because the cubitus has a very easy surgical access (just under the skin, mostly). On the other hand, opening the grave after decomposition to take the bone, make those marks, and put it back, seems too much work to achieve the same result…

If the marks had been on another anatomical site (say, the anterior aspect of the sacrum, or the inner aspect of the cranium, etc.) maybe the butchery needed to mark the bones would not be worth it (especially for a relative of the deceased), but in this case I hope they have a good reason to support why it must have been made after decomposition.

EDIT (4 AUG 2018): The published paper on this specific burial and the marks: Ritual position and “tattooing” techniques in the funeral practices of the “Barrow cultures” of the Pontic-Caspian steppe/forest-steppe area Porohy 3A, Yampil region, Vinnytsia Oblast: Specialist analysis research perspectives, by Żurkiewicz et al. (2018).

See also on the same region Eneolithic, Yamnaya and Noua culture cemeteries from the first half of the 3rd and the middle of the 2nd millennium BC, Porogy, site 3A, Yampil region, Vinnitsa oblast: Archaeometric and Chronometric Description, Ritual and Tazonomic-Topogenetic identification, by Viktor Klochko et al. (2015), B-P S, vol. 20, P. 78-141.

Related

- The unique elite Khvalynsk male from a Yekaterinovskiy Cape burial

- Kurgan origins and expansion with Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka chieftains

- About Scepters, Horses, and War: on Khvalynsk migrants in the Caucasus and the Danube

- Steppe and Caucasus Eneolithic: the new keystones of the EHG-CHG-ANE ancestry in steppe groups

- The Caucasus a genetic and cultural barrier; Yamna dominated by R1b-M269; Yamna settlers in Hungary cluster with Yamna

- Consequences of Damgaard et al. 2018 (II): The late Khvalynsk migration waves with R1b-L23 lineages