Researchers involved in the investigation of the Yampil Barrow Complex are taking the opportunity of their latest genetic paper to publish and upload more papers in Academia.edu.

NOTE. These are from the free volume 22 of Baltic-Pontic Studies, Podolia “Barrow Culture” Communities: 4th/3rd-2nd Mill. BC. The Yampil Barrow Complex: Interdisciplinary Studies, whose website gives a warning depending on your browser (because of the lack of secure connection). Here is a link to the whole PDF.

Here are some of them, with interesting excerpts (emphasis mine):

1. Kurgan rites in the Eneolithic and Early Bronze age Podolia in light of materials from the funerary ceremonial centre at Yampil, by Piotr Włodarczak (2017).

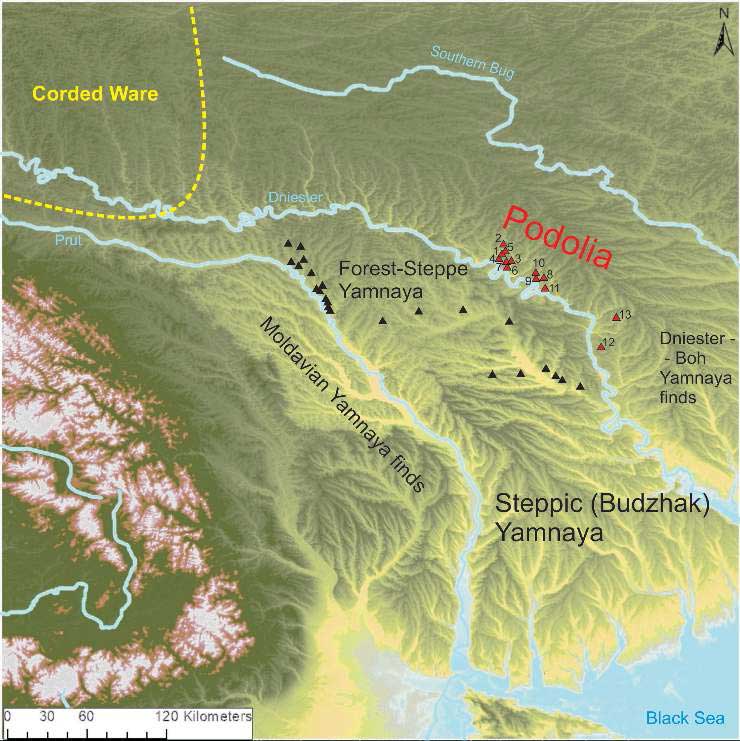

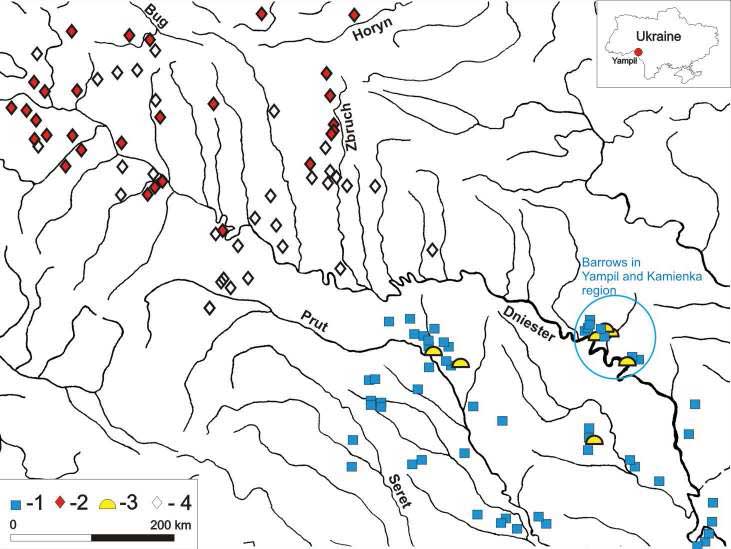

The particular interest in this group stemmed from its specific location within the “Yamnaya cultural-historical entity”: its exposure to Central European Corded ware culture (further as CWC) on the one hand, and discernible contact with communities representing the Globular Amphorae culture (GAC), expanding to the south-east, on the other [e.g. Szmyt 1999; 2000]. The location on the fringes of the north-western variant of the Yamnaya culture (YC) [acc. to Merpert 1974; cf Rassamakin 2013a; 2013b; Rassamakin, Nikolova 2008] opened up an interesting perspective for tracing the transfer of Central European cultural patterns to the North Pontic area, and for determining the specificity of the cultural model of steppe communities, which due to their geographic location seemed somehow predestined for westward expansion.

Podolia kurgans originate from various stages of the Eneolithic and Early bronze ages, and this chronological diversity is reflected in differences in construction of mounds and central graves for which kurgans were originally built (being burials of the “kurgans’ founders”). These oldest burials link with various Eneolithic and YC communities, and the taxonomic attribution of some of the phenomena discussed here poses difficulties. This stems from the nature of the finds, which are sometimes only slightly distinctive and often retrieved from contexts difficult to interpret (e.g. from kurgans damaged to a significant degree). Another reason for the high discordance and ambiguity of opinions lies in the nature of the problem itself, since taxonomic definitions can be no more than proxies for cultural processes which are both fluid and multi-directional. This is particularly evident for phenomena associated with the Eneolithic and the very beginnings of the Bronze Age in steppe and forest-steppe areas [e.g. Rassamakin 2013; Manzura 2016], while later stages (the classic and late YC) are marked by much more regularity in terms of funeral rituals. Funerary behaviours displayed by Eneolithic steppe groups were the outcome of intercultural relationships and often combined elements borrowed from different milieus [e.g. Rassamakin 2008: 215, 216]. One consequence of this is the multitude of approaches to the description of Eneolithic phenomena proposed in the literature, with the controversies the situation creates. This is also true for the Podolia kurgans discussed here, where chronology is relatively easy to interpret while taxonomical attributions are much more difficult. A good example in this context is a recently published complex at Prydnistryanske, which has been linked either with the late Trypilia group of Gordinești [Klochko et al 2015d] or with the Eneolithic steppe formation known as Zhivotilovka-Volchansk [Manzura 2016], or recently with the Bursuceni group [Demcenko 2016].

A distinct feature of Podolia kurgans having YC burials is the multi-phase nature of their mounds, a feature recorded throughout the North Pontic area. It is particularly evident in the cases of sequences of burials (typically two burials) placed in the central parts of kurgans and connected with separate stages of the mound’s construction. In this context, the temporal and cultural relationship between the older and younger burial becomes a very interesting issue. Younger burials typically revealed traits characteristic of the YC complex, while older ones were often different and distinguished by a different shape of the grave pit and sometimes a different arrangement and orientation of the body as well. In the most evident cases, older pits held a body in the extended position, reminiscent of the Postmariupol/ Kvityana tradition (…). In such cases, the older grave often stands out with a funerary tradition diverging from model YC behaviours, in terms of orientation, body position, and constructional features.

Kvitjana and Trypillia

The Pre-Yamnaya (Eneolithic) phase came to be distinguished in kurgan cemeteries from the Podolie region after the discovery of burials in extended position (i.e. of the Kvityana/Postmariupol type) at Ocniţa (Fig 10: 2, 3) [kurgans 6 and 7; Manzura et al 1992] and Tymkove (Fig 10: 1) [Subbotin et al 2000, 84, ris 3: 4]. In all these three cases the burials marked the oldest phase of mound construction, and later YC burials were dug into the central part of the kurgan, which entailed the remodelling and considerable enlargement of the mound. Both the chronological and taxonomic positions of extended burials in the North Pontic area are subjects of debate [e.g. Manzura 2010; Rassamakin 2013; Ivanova 2015, 280-282] (…)

The chronological position of graves with burials in extended position can be narrowed down thanks to stratigraphic observations made in kurgans at Bursuceni, between the Dniester and Prut rivers [Yarovoy 1978]. Graves from this site were younger than the burials representing the Zhivotilovka-Volchansk tradition and older than those linked with the early phase of YC based on a relatively compact series of radiocarbon dates obtained for graves of the Zhivotilovka-Volchansk group, the chronology of burials in extended position can be determined as the very close of the 4th – beginning of the 3rd millennia BC (most likely around 3100-2800 BC).

Early and late Yamna

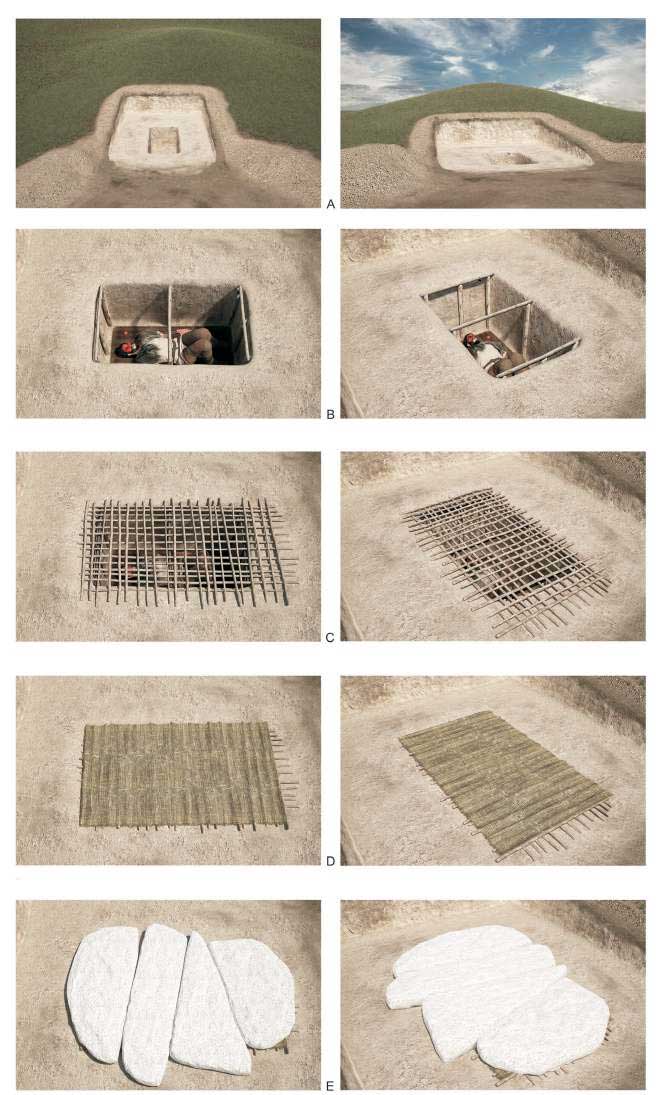

A model ceremonial-funerary complex created by a YC community is a group of kurgans in Pysarivka village [harat et al 2014: 104-165]. Nine mounds have been explored there, of which eight (1, 3-9) yielded central burials of YC sharing a number of similar features (Fig 13). The deceased were placed in regular, rectangular pits having vertical walls Vykids (mounds of soil extracted while digging grave pits) formed regular narrow walls surrounding each grave, and seem to have been integral elements of sepulchral architecture. Chambers were covered with 5-7 timbers/planks arranged parallel to the grave’s longer axis. Another characteristic element was that of wooden stakes driven symmetrically into the bottom along grave chamber edges, recorded in four cases. The deceased were laid on their backs, in a contracted position with the knees up. The head was as a rule turned to W, with possible deflections towards NW or SW Skeletons bore traces of painting with ochre.

The role of south-eastern connections at the early stage of YC development can also be seen in grave IV/4 at Prydnistryanske. This is indicated by a combined (wood and stone) roof construction involving stela-like slabs, and by the skull of the deceased characteristically painted with red pigment. The absolute date obtained for grave IV/4 (ca 3100-3000 bC) suggests its early provenance [Goslar et al 2015]. The grave was most likely connected with the oldest stage of enlargement of the Eneolithic barrow [Klochko et al 2015].

The middle phase of YC is quite clearly evident in Podolia kurgans, it is marked by burials dug into the existing mounds. These are either single burials inserted into different parts of the mounds, or groups of graves forming arches around a central part. Graves with steps leading to the burial chamber are typical of that stage, and they were wider than those in the centres of kurgans. Chambers were typically roofed with planks or timbers placed perpendicularly to the grave’s longer axis burials on one side and burials on the back but leaning to either side become more numerous, and upper limbs were most often placed in A, G, H, or I arrangements ceramic vessels become more common in graves, including forms indicative of contacts with GAC and CWC milieus.

2. The previously announced paper on a specific burial showing postmortem marks: Ritual position and “tattooing” techniques in the funeral practices of the “Barrow cultures” of the Pontic-Caspian steppe/forest-steppe area Porohy 3A, Yampil region, Vinnytsia Oblast: Specialist analysis research perspectives, by Żurkiewicz et al. (2018):

Based on the anatomical properties of the structure of a human body, the histological structure of the skin and location of the dye used for tattooing, having conducted an analysis of postmortem changes occurring within the skin after death, and having taken into consideration the continuous and regular nature of the pattern on the ulnae of the individual from grave no. 10, an interdisciplinary team of researchers has concluded that there is no possibility of a transfer of tattoo dye from the skin onto the surface of an individual’s bone.

The analysis of two ulnae documented in this article indicates that the patterns were made using tree tar, postmortem and directly onto the skeletonised human remains. The placement of the individual’s ulnae in grave no. 10 (Fig. 10), and the location of patterns on the upper skin surface, that is, on surfaces accessible without changing the arrangement of the body, may suggest that the patterns were created on the skeletonised remains without the need to change their placement in the pit (= in situ).

The present conclusions ought to see the beginning of a wider research programme focused on the analysis of the techniques used to create decorations on bones in “kurgan cultures” communities in the context of the Pontic-Caspian Region.

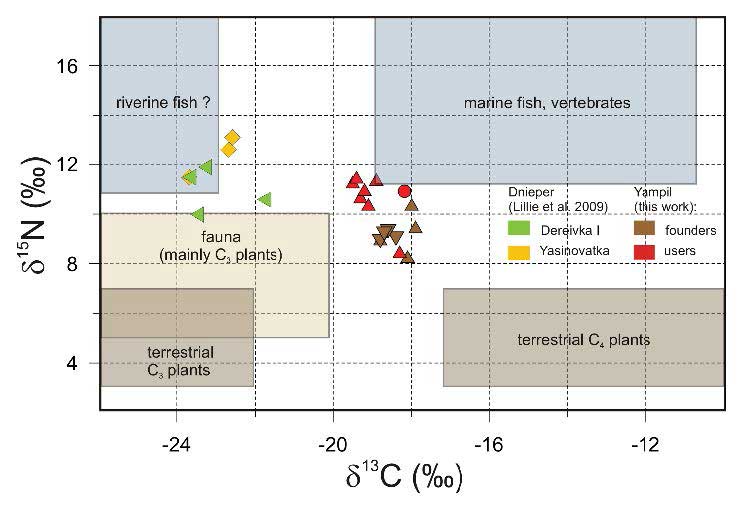

3. Builders and users of ritual centres, Yampil barrow complex: studies of diett based on stable carbon nitrogen isotope composition, by Goslar et al. (2017).

Foxtail millet caryopses are used to make primarily flour, groats and pancakes [lityńska-zając, wasylikowa 2005: 109]. Grains and flour are easily digestible and as such, they are recommended to infants and the elderly. Grains are also fed to fowl and poultry in Asia, foxtail millet is used to make beer and wine, while in China it is also used for medicinal purposes [Hanelt 2001 (Ed )]. Various dishes and beverages made from broomcorn and foxtail millet caryopses in Eurasia are listed by Sakamoto [1987a]. Detailed ethnobotanical studies of the cultivation, crop processing and food preparation in the Iberian Peninsula were presented by Moreno-Larrazabal et al.[2015] .

The geographical area under discussion can be related to historical and ethnographic data indicating the use of grits and groats in the diet. They had been known in the menus of European societies since the ‘pre-agrarian’ times. The isotope finding of millet domination in the diet of middle Dniester Yampil Barrow Complex, complemented by bioarchaeological data from the upper steppe Dniester area (from the similarly ‘early-barrow’ Usatovo group/culture with strongly marked ‘eastern’ civilization influences), makes it reasonable to consider the possibility that already in the prologue of late Eneolithic-Early bronze barrow culture (3300- 2800 BC) development there was a clear dividing line of millet groats use – or millet presence – that is, so-called yagla groats (yagla, yagly = millet in Old Slavic languages).

Related

- On the origin of haplogroup R1b-L51 in late Repin / early Yamna settlers

- Mitogenomes show likely origin of elevated steppe ancestry in neighbouring Corded Ware groups

- Corded Ware culture origins: The Final Frontier

- Sredni Stog, Proto-Corded Ware, and their “steppe admixture”

- Kurgan origins and expansion with Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka chieftains

- About Scepters, Horses, and War: on Khvalynsk migrants in the Caucasus and the Danube

- Steppe and Caucasus Eneolithic: the new keystones of the EHG-CHG-ANE ancestry in steppe groups

- The Caucasus a genetic and cultural barrier; Yamna dominated by R1b-M269; Yamna settlers in Hungary cluster with Yamna

- The concept of “Outlier” in Human Ancestry (III): Late Neolithic samples from the Baltic region and origins of the Corded Ware culture

- North Pontic steppe Eneolithic cultures, and an alternative Indo-Slavonic model

- New Ukraine Eneolithic sample from late Sredni Stog, near homeland of the Corded Ware culture

- The renewed ‘Kurgan model’ of Kristian Kristiansen and the Danish school: “The Indo-European Corded Ware Theory”