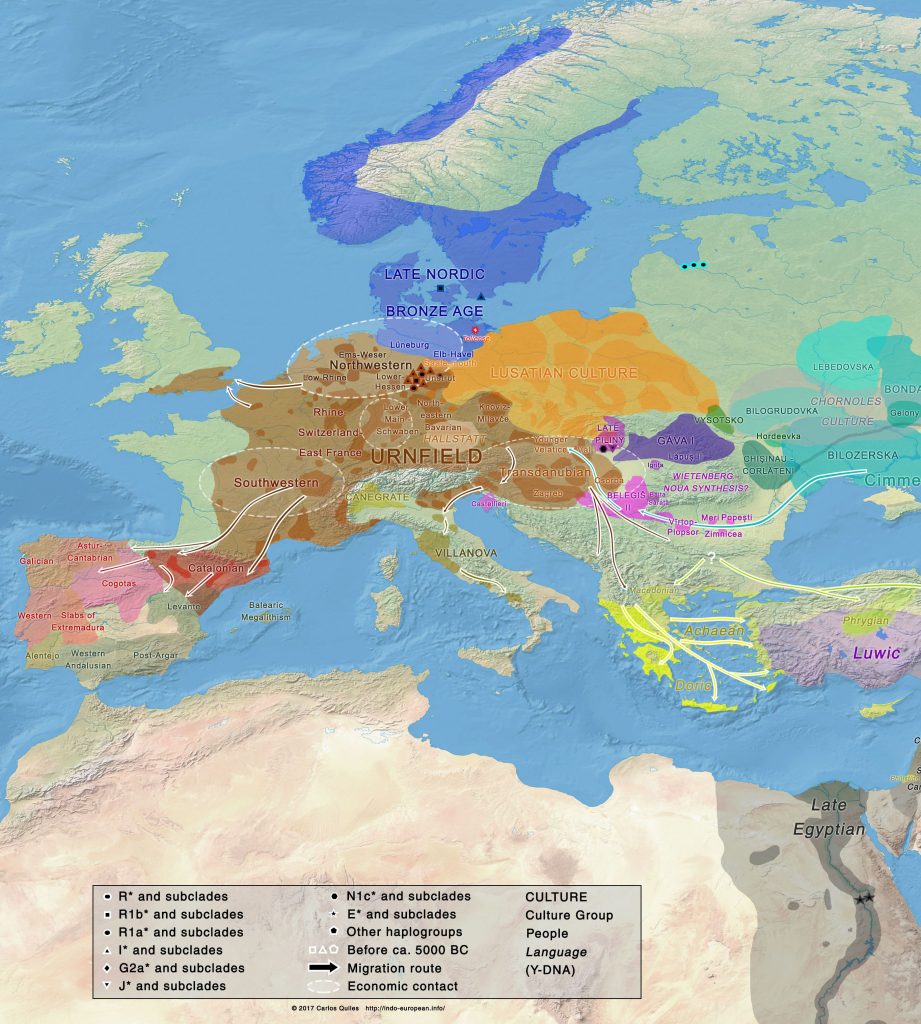

It was reported long ago that genetic studies were being made on remains of a surprisingly big battle that happened in the Tollense valley in north-eastern Germany, at the confluence between Nordic, Tumulus/Urnfield, and Proto-Lusatian/Lusatian territories, ca. 1200 BC.

At least 130 bodies and 5 horses have been identified from the bones found. Taking into account that this is a small percentage of the potential battlefield, around 750 bodies are expected to be buried in the riverbank, so an estimated 4,000-strong army fought there, accounting for one in five participants killed and left on the battlefield.

Body armour, shields, helmet, and corselet used may have needed training and specialised groups of warriors, with their organisation being a display of military force. According to Kristiansen , this battle is therefore unlike any other known conflict of this period north of the Alps – circumscribed to raids by small groups of young men –, and may have heralded a radical change in the north, from individual farmsteads and a low population density to heavily fortified settlements.

The Urnfield culture (ca. 1300-750 BC) is associated with the rise of a new warrior elite, and the formation of new farming settlements and their urnfields. In some areas there is continuity from Tumulus to Urnfield culture, with narrowing and concentration of settlements along the river valleys, but there is also wide-ranging migrations. These migrations are similar to those seen later in the La Tène culture. This period is also coincident with the time of the mythical battle of Troy, with the collapse of the Mycenaean civilisation, and with the raids of Sea People in Egypt, and the marauders of the Hittites.

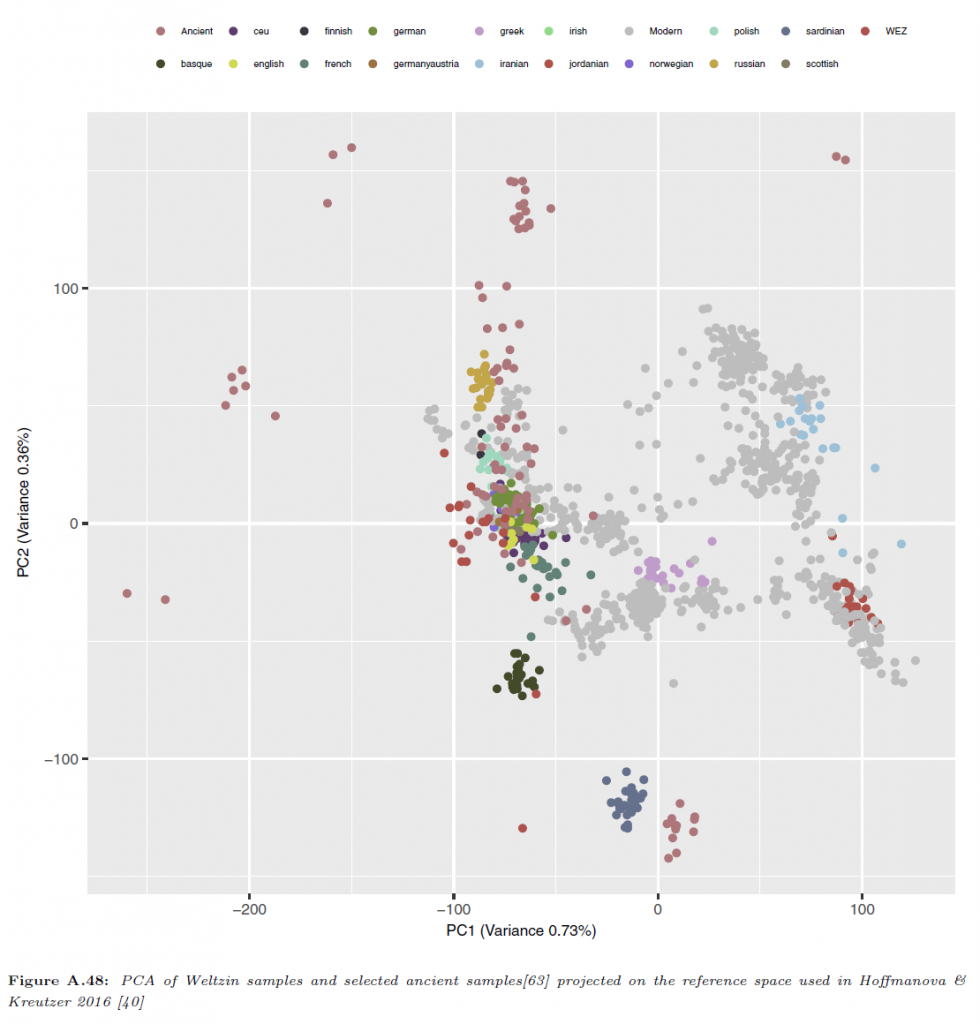

Chemical traces already suggested that warriors fighting in Tollense came from far away, with only a few showing values typical of the northern European plain. A recently published PhD dissertation, Addressing challenges of ancient DNA sequence data obtained with next generation methods, by Christian Sell (2017) has not confirmed this:

The majority of sampled individuals fall within the variation of contemporary northern central European samples (including Nordic Late Neolithic and Bronze Age and Únětice samples); however, there are also some outliers closer to Neolithic LBK and modern Basques, suggesting that central and western European cultures were still at that time closely interconnected, continuing thus the connections created during the Bell Beaker expansion a thousand years earlier. The genetic similarity of most samples to modern western Slavic populations (as well as Austrians and Scots) gives support to the origin of Balto-Slavic in Bronze Age north-central Europe, and more specifically in the Lusatian culture.

The Indo-European demic diffusion model supports the origin of Pre-Balto-Slavic in north-central Europe, with Únětice and Mierzanowice/Nitra groups as its potential homeland, from a common North-West Indo-European parent language (expanded through East Bell Beaker). Proto-Lusatian is therefore the best candidate for its initial development, and Lusatian for its eastern expansion, before its separation into its two main dialects (or maybe three, if Baltic is to be divided in two branches).

In fact, scarce aDNA from late Urnfield populations from its north-eastern territories, in Saxony – near the Lusatian culture –, already show a mixture of lineages, which suggest genetic continuity with older cultures (or more likely a resurge) after the Bell Beaker expansions: R1a1a1b1a-Z282 lineage was found in Halberstadt (ca. 1085 BC), and of the eight males studied from the Lichtenstein cave (ca. 1000 BC), five were of haplogroup I2a2b-L38, two of haplogroup R1a1-M459, and one of haplogroup R1b-M343.

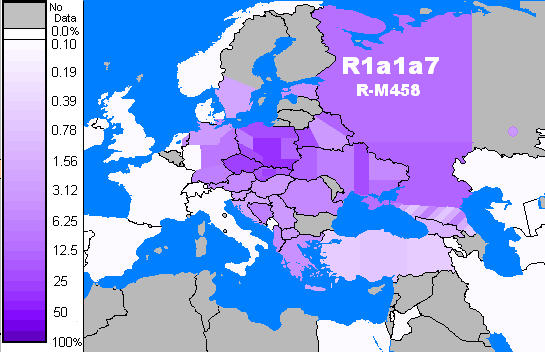

Regarding modern populations, the eastern and western peaks in R1a1a1b1a1-M458 lineages might support a west-east migration, as well as an east-west migration, and indeed both in different periods, which is expected to be found if Lusatian is linked to the initial eastward expansion of Balto-Slavic during the Bronze and Iron Ages, and later younger subclades are linked to the West Slavic expansion to the west during Antiquity.

Now, if this is so, then we have to accept that these territories of north-central Europe (between East Germany and Poland), occupied earlier by Corded Ware cultures, adopted Balto-Slavic only after the Bell Beaker expansion; therefore, models arguing for Balto-Slavic origins in east European late Corded Ware groups (or heir cultures), like Trzciniec, Chornoles, Bilozerska, or Milograd (see e.g. the article on Wikipedia) have to be rejected. We also know that Pre-Germanic could have only formed in the Nordic Late Neolithic, after the cultural unification of the Dagger Period, heraled by the arrival of Bell Beakers; and that Indo-Iranian was the language of the Sintashta-Petrovka culture, which had absorbed the previous (Yamna-related) Poltavka culture.

But, if Indo-European was only spoken at both ends of territories previously occupied by Corded Ware cultures – stretching from Scandinavia to the Urals, including the Baltic region… what language did Corded Ware peoples actually speak? The most likely one? Uralic, indeed.

Related:

- Forces driving grammatical change are different to those driving lexical change

- New Ukraine Eneolithic sample from late Sredni Stog, near homeland of the Corded Ware culture

- Germanic–Balto-Slavic and Satem (‘Indo-Slavonic’) dialect revisionism by amateur geneticists, or why R1a lineages *must* have spoken Proto-Indo-European

- Another hint at the role of Corded Ware peoples in spreading Uralic languages into north-eastern Europe, found in mtDNA analysis of the Finnish population

- Wiik’s theory about the spread of Uralic into east and central Europe, and the Uralic substrate in Germanic and Balto-Slavic