Open access Complex history of dog (Canis familiaris) origins and translocations in the Pacific revealed by ancient mitogenomes, by Creig et al., Scientific Reports (2018).

Abstract:

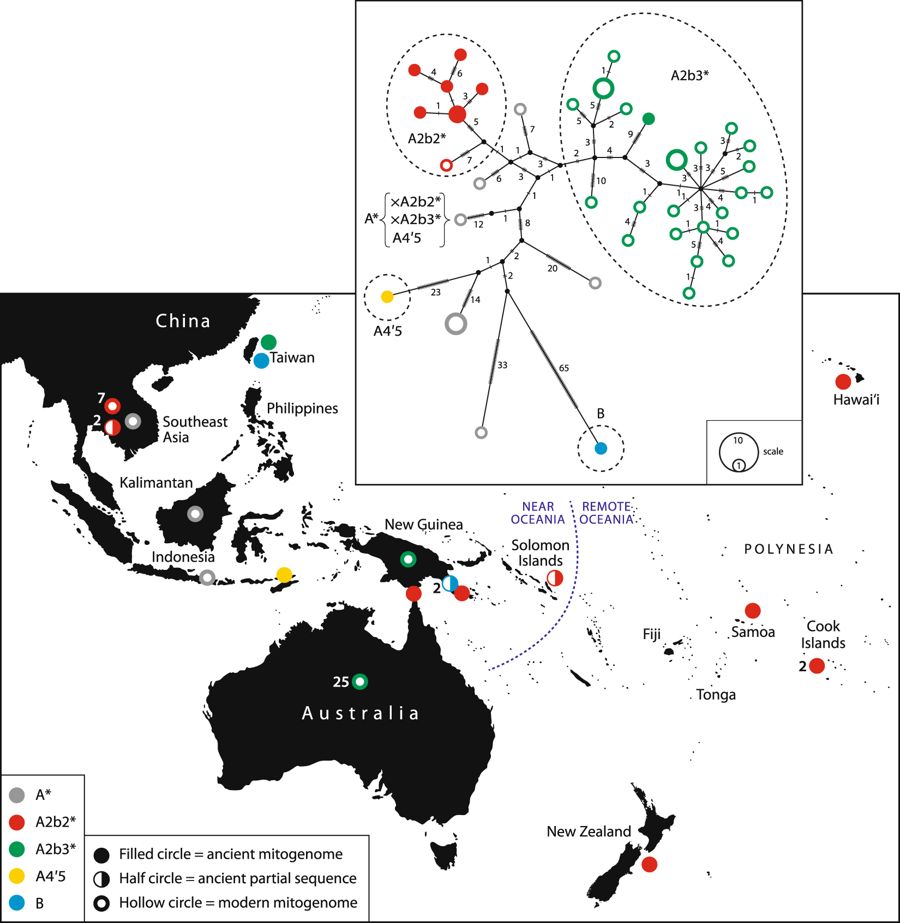

Archaeological evidence suggests that dogs were introduced to the islands of Oceania via Island Southeast Asia around 3,300 years ago, and reached the eastern islands of Polynesia by the fourteenth century AD. This dispersal is intimately tied to human expansion, but the involvement of dogs in Pacific migrations is not well understood. Our analyses of seven new complete ancient mitogenomes and five partial mtDNA sequences from archaeological dog specimens from Mainland and Island Southeast Asia and the Pacific suggests at least three dog dispersal events into the region, in addition to the introduction of dingoes to Australia. We see an early introduction of dogs to Island Southeast Asia, which does not appear to extend into the islands of Oceania. A shared haplogroup identified between Iron Age Taiwanese dogs, terminal-Lapita and post-Lapita dogs suggests that at least one dog lineage was introduced to Near Oceania by or as the result of interactions with Austronesian language speakers associated with the Lapita Cultural Complex. We did not find any evidence that these dogs were successfully transported beyond New Guinea. Finally, we identify a widespread dog clade found across the Pacific, including the islands of Polynesia, which likely suggests a post-Lapita dog introduction from southern Island Southeast Asia.

Conclusion:

The dispersal of dogs across the Pacific is inseparably linked to the relationships between dogs and people. Unlike movement across continental landmasses, Pacific dogs must have been transported by people across the waters that separate islands. The ancient mitogenomes sequenced from archaeological dog specimens presented here offer a novel series of individual insights into the history of dog translocation from Southeast Asia as it occurred prior to the influence of modern European dog breeds. We generated seven mitogenomes and five partial sequences from ancient MSEA, ISEA and Pacific dogs, and four modern dingoes. Despite the small sample size, our results reveal levels of complexity and discontinuity in the introduction and movement of dogs, which are mirrored in the archaeological and linguistic evidence, suggesting at least three introductions of dogs to the wider Pacific region, in addition to the earlier appearance of the dingo in Australia. Further mtDNA studies of ancient dogs and modern village populations throughout the region may contribute additional data that can be used to evaluate these hypothesised dispersals. Autosomal and Y-chromosome analyses also have the potential to generate additional information about dog dispersal, which could reveal different dispersal signatures based on sex, or phenotypic characteristics, though the environmental conditions in the region are not particularly conducive to aDNA preservation.

Our molecular genetic analyses reveal one of the earliest dogs present in ISEA around 3,000 years ago from Timor-Leste possesses a mtDNA lineage not found elsewhere in the region. We also found similarities between mtDNA of modern dingoes and NGSDs and an ancient Taiwanese sequence, which supports previous observations about possible links between Y-chromosome markers of modern dingoes and a modern Taiwanese sample. More work is required to address whether these connections reflect the genetic diversity of a shared ancestral population in mainland China, or attest to a currently unknown dispersal event linking the two populations. Archaeological evidence for the introduction of dogs to Oceania as part of the LCC is extremely limited. Nonetheless, we demonstrate that mitogenomes from dogs in terminal Lapita and post-Lapita levels of archaeological sites along the south coast of mainland New Guinea also show affinities with an Iron Age dog specimen from Taiwan, raising the possibility of at least one introduction of dogs during Austronesian expansions ultimately from the north. Finally, we have identified a major late introduction of dogs across the islands of Oceania beginning around 2,000 years ago, which appears to have originated in MSEA, not Taiwan, and culminated in the establishment of dog populations in initial colonisation-era sites throughout East Polynesia.

Also related, open access Elucidating biogeographical patterns in Australian native canids using genome wide SNPs, by Cairns et al., PLOS One (2018).

Abstract:

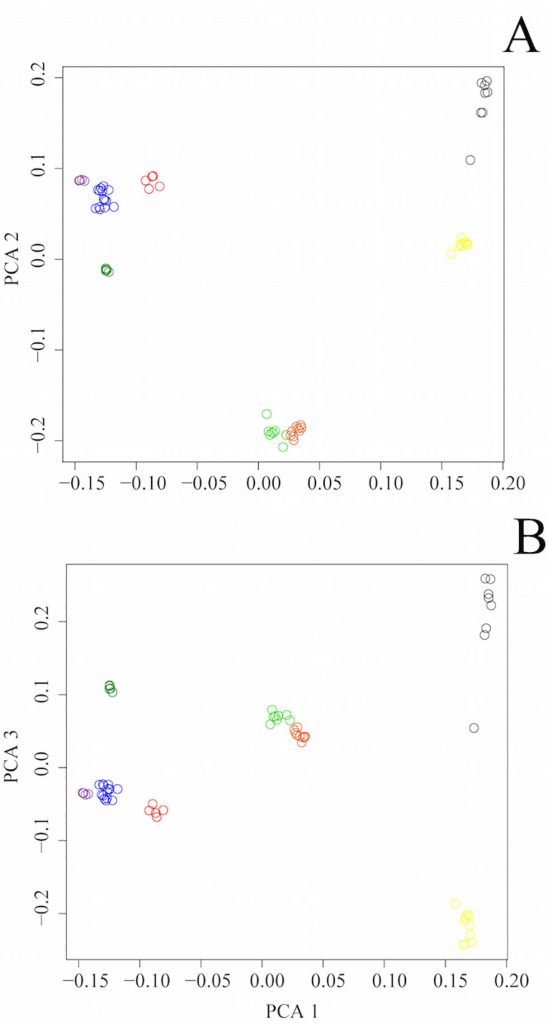

Dingoes play a strong role in Australia’s ecological framework as the apex predator but are under threat from hybridization and agricultural control programs. Government legislation lists the conservation of the dingo as an important aim, yet little is known about the biogeography of this enigmatic canine, making conservation difficult. Mitochondrial and Y chromosome DNA studies show evidence of population structure within the dingo. Here, we present the data from Illumina HD canine chip genotyping for 23 dingoes from five regional populations, and five New Guinea Singing Dogs to further explore patterns of biogeography using genome-wide data. Whole genome single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data supported the presence of three distinct dingo populations (or ESUs) subject to geographical subdivision: southeastern (SE), Fraser Island (FI) and northwestern (NW). These ESUs should be managed discretely. The FI dingoes are a known reservoir of pure, genetically distinct dingoes. Elevated inbreeding coefficients identified here suggest this population may be genetically compromised and in need of rescue; current lethal management strategies that do not consider genetic information should be suspended until further data can be gathered. D statistics identify evidence of historical admixture or ancestry sharing between southeastern dingoes and South East Asian village dogs. Conservation efforts on mainland Australia should focus on the SE dingo population that is under pressure from domestic dog hybridization and high levels of lethal control. Further data concerning the genetic health, demographics and prevalence of hybridization in the SE and FI dingo populations is urgently needed to develop evidence based conservation and management strategies.

As I said in a previous post, the study of dogs may be useful to trace population migrations and to assess strong cultural contacts. Especially, as in this case, when crossbreeding among cultures is not easy…

Related:

- Canid Y-chromosome phylogeny reveals distinct haplogroups among Neolithic European dogs

- Linguistic continuity despite genetic replacement in Remote Oceania

- Population turnover in Remote Oceania shortly after initial settlement

- Language continuity despite population replacement in Remote Oceania

- Genomic history of South-East Asia: eastern Polynesians, Peninsular Malaysia and North Borneo

- Islands across the Indonesian archipelago show complex patterns of admixture