Recent open access Symbols in motion: Flexible cultural boundaries and the fast spread of the Neolithic in the western Mediterranean, by Rigaud, Manen, García-Martínez de Lagrán, PLOS One (2018).

Abstract (emphasis mine):

The rapid diffusion of farming technologies in the western Mediterranean raises questions about the mechanisms that drove the development of intensive contact networks and circulation routes between incoming Neolithic communities. Using a statistical method to analyze a brand-new set of cultural and chronological data, we document the large-scale processes that led to variations between Mediterranean archaeological cultures, and micro-scale processes responsible for the transmission of cultural practices within farming communities. The analysis of two symbolic productions, pottery decorations and personal ornaments, shed light on the complex interactions developed by Early Neolithic farmers in the western Mediterranean area. Pottery decoration diversity correlates with local processes of circulation and exchange, resulting in the emergence and the persistence of stylistic and symbolic boundaries between groups, while personal ornaments reflect extensive networks and the high level of mobility of Early Neolithic farmers. The two symbolic productions express different degrees of cultural interaction that may have facilitated the successful and rapid expansion of early farming societies in the western Mediterranean.

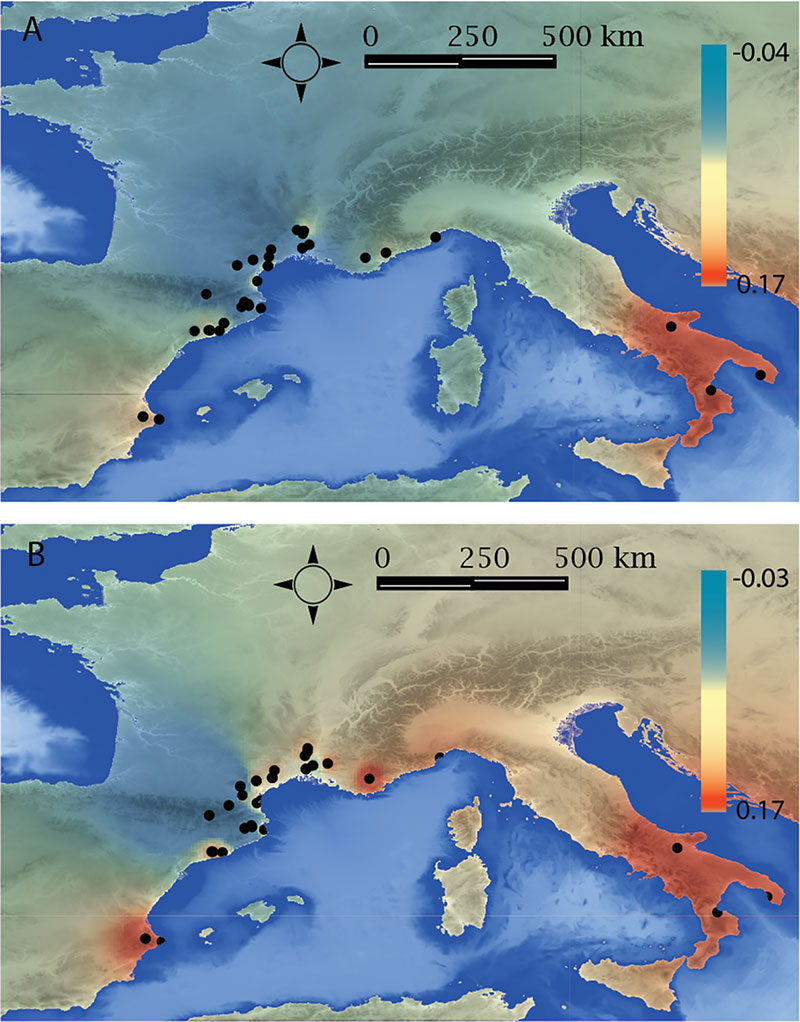

The maps of interpolated pottery decorative techniques and bead-type diversities throughout the western Mediterranean show the highest interpolated values in southern Italy (Fig B). Hotspots restricted to the east of the Rhône Valley in southern France and eastern Iberia are also visible on the map of bead-type association diversity. Conversely, southern France and eastern Iberia are characterized by lower interpolated values on the map of pottery decorative techniques diversity (Fig A).

Conclusions:

Our results shed light on the cultural mechanisms responsible for the complex cultural geography of the western Mediterranean during the transition to farming. Pottery decorations participated in restrained networks in which geographical proximity and local processes of transmission played an influential role. Bead-type associations were used to tell multiple stories about social identities, were especially resistant to change and are characterized by a greater stability through time and space. The high level of cultural connection between the early farming communities favored movement, interaction and exploration and likely represented a successful strategy for their rapid expansion in the western Mediterranean. Cultural boundaries persisted despite a flow of individuals and symbolic transfer across them.

Genetic studies indicate that the last foragers and the first farmers developed social and cultural relationships more closely tied than previously indicated through components of the material culture [139]. Biological data and chronological models support a pattern of diffusion implying geographically discontinuous contacts between local foragers and incoming farmers, but repeated in time [9,140,141]. This process of diffusion conjointly occurred with changes in material culture, including pottery decorations and personal ornaments. Pottery production represents a technological innovation mostly associated with the Neolithic way of life in the western Mediterranean. Pottery decorations were likely particularly sensitive to interactions, leading to their high variability in time and space in order to reinforce group membership. Conversely, personal ornaments were less inclined to change in space and time. Their production by both local foragers and incoming farmers implies different cultural readjustments that led to a completely different pattern of variation in time and space. The preservation of the foragers’ personal ornament styles (and likely also meanings) within emerging farming communities [20,58] has probably contributed to the maintenance of their stability through time and space.

The two symbolic productions appear as a polythetic set of cultural behaviors dedicated to mediating early farmer identities in many ways, and personal ornaments likely reflected the most entrenched and lasting facets of farmers’ ethnicity.

This research is similar to the recent one by Kılınç et al. (2018) studying the same processes initially in Anatolia and the Aegean. With this one it may also be concluded that Archaeology is necessary to assess meaningful cultural (and thus potential ethnolinguistic) change, beyond gross genetic inflows, even in the case of the Near Eastern farmer expansion waves.

Related:

- Migration vs. Acculturation models for Aegean Neolithic in Genetics — still depending strongly on Archaeology

- Agricultural origins on the Anatolian plateau

- The myth of mixed language, the concepts of culture core and package, and the invention of ‘Steppe folk’

- Genetic origins of Minoans and Mycenaeans and their continuity into modern Greeks

- Consequences of O&M 2018 (II): The unsolved nature of Suvorovo-Novodanilovka chiefs, and the route of Proto-Anatolian expansion

- The over-simplistic “Kossinnian Model”: homogeneous peoples speaking a common language within clearly delimited cultures