An interesting essay by Arika Okrent has appeared in Aeon – Is linguistics a science? It concerns the central position of Chomsky’s Universal Grammar to modern Linguistics, and revolves around a story in Tom Wolfe’s book The Kingdom of Speech (2016), Everett’s discovery of the Pirahã culture’s (and language’s) emphasis on the here and now: not embedding one phrase inside another, the simple kinship system, lack of numbers, and absence of fiction or creation myths. Some excerpts of the essay:

This looks suspiciously like defiance of a central feature of the scientific archetype, one first put forward by the philosopher Karl Popper: theories are not scientific unless they have the potential to be falsified. If you claim that recursion is the essential feature of language, and if the existence of a recursionless language does not debunk your claim, then what could possibly invalidate it?

(…)

In an interview with Edge.org in 2007, Everett said he emailed Chomsky: ‘What is a single prediction that universal grammar makes that I could falsify? How could I test it?’ According to Everett, Chomsky replied to say that universal grammar doesn’t make any predictions; it’s a field of study, like biology.

(…)

By contrast, good theories or hypotheses are those that allow you to search for contrary evidence. Thus Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity made a very specific prediction about the effect of gravity on light, which could be subsequently tested during the solar eclipse of 1919. Unlike astrology or Freudianism, relativity could be contradicted. It was possible to conceive of an observation that would conflict with one’s expectations (although the eclipse ultimately vindicated Einstein). The capacity to be disproved is what makes general relativity scientific.

(…)

In Chomsky’s formulation, we are not just after a set of abstract rules that account for the things we can see and hear, but one that explains why they are the way they are. In the late 1970s, Chomsky began to refer to this method of enquiry as the ‘Galilean style’

(…)

Chomsky’s Galilean vision was that our intuitive judgments about language stem from an innate language faculty, a universal grammar underlying the human capacity for language. His project is to determine the essential nature of that universal grammar – not the nature of language, but the nature of the human capacity for language. The distinction is a subtle one.

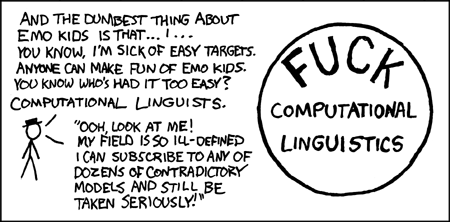

Regarding the pseudoscience claims about Linguistics, or in this case Chomsky’s Universal Grammar, and the common answer to such criticism of linguistic abstractions by their authors (asserting that they can be “neither right nor wrong” but only “fecund or sterile”), they reminded me of an old XKCD comic which sums up this line of reasoning quite well: